Read Short Denver Post Article

By Dianne Zuckerman

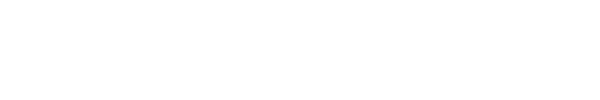

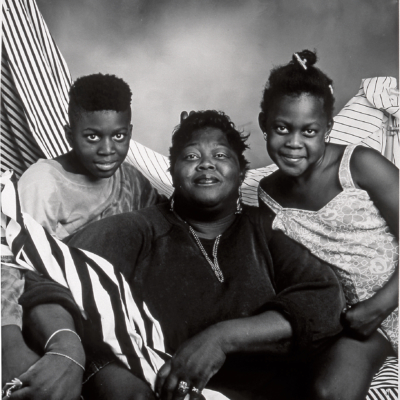

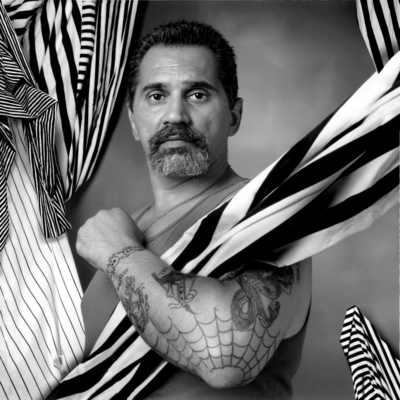

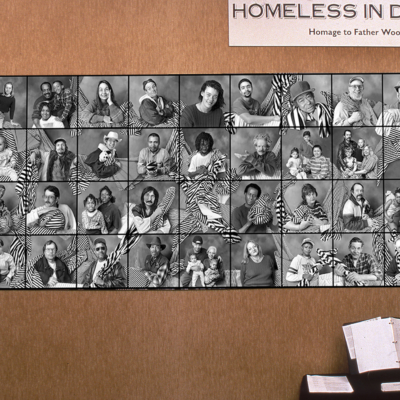

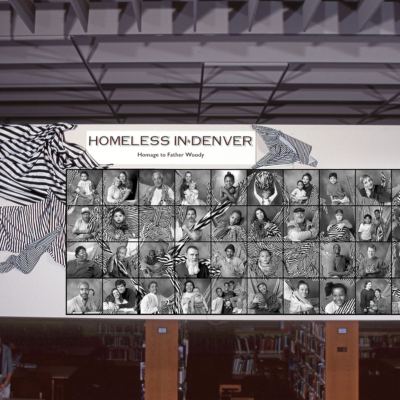

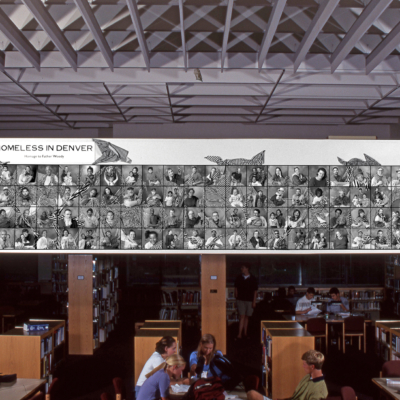

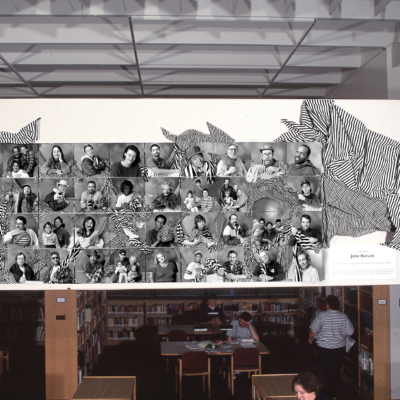

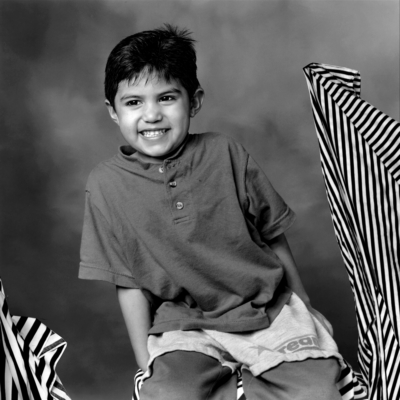

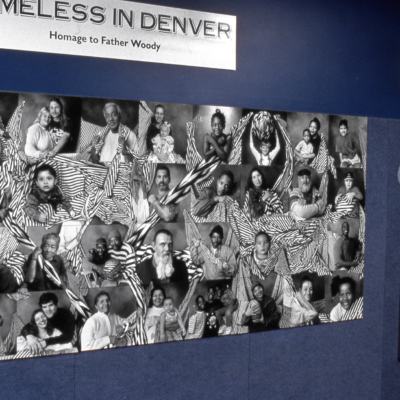

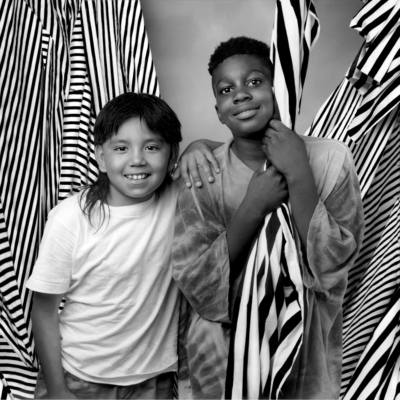

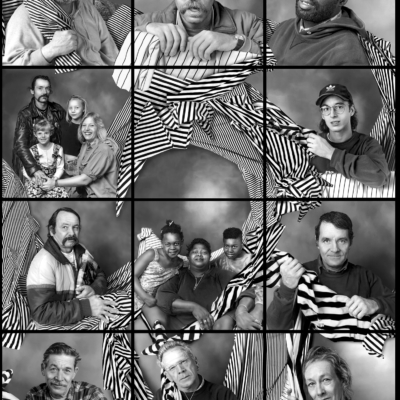

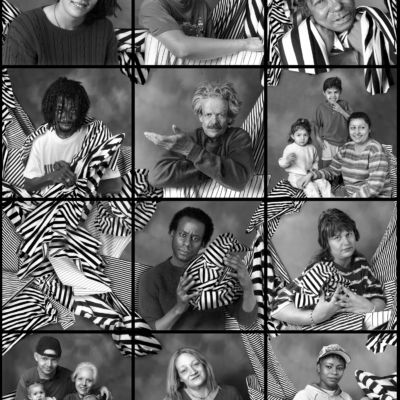

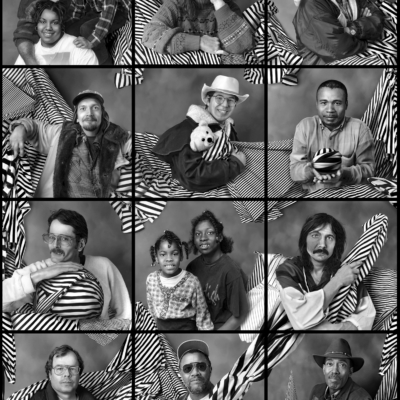

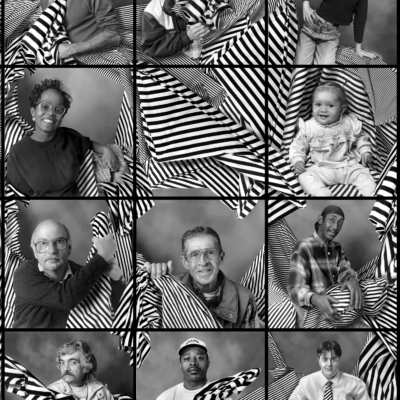

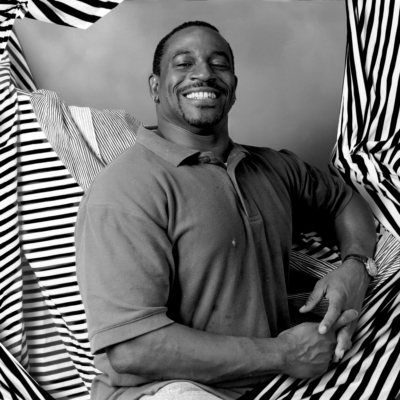

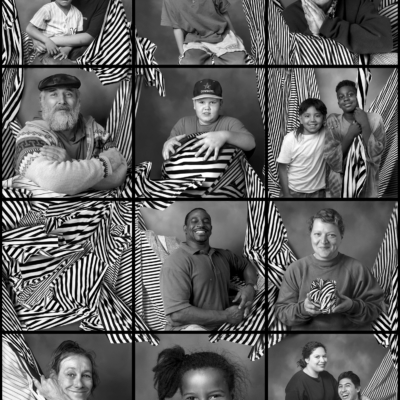

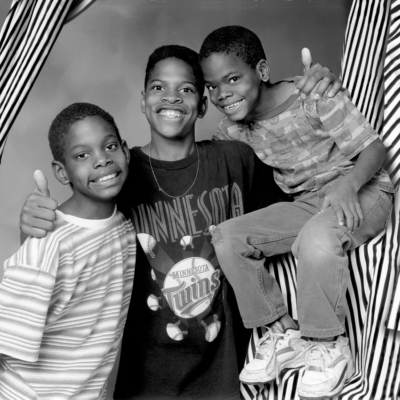

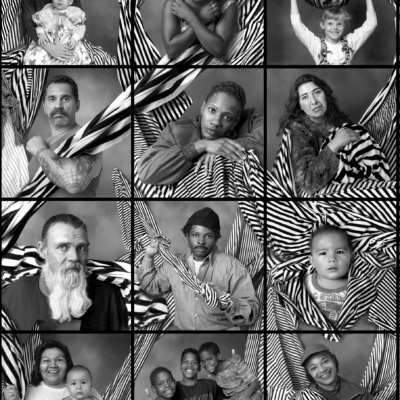

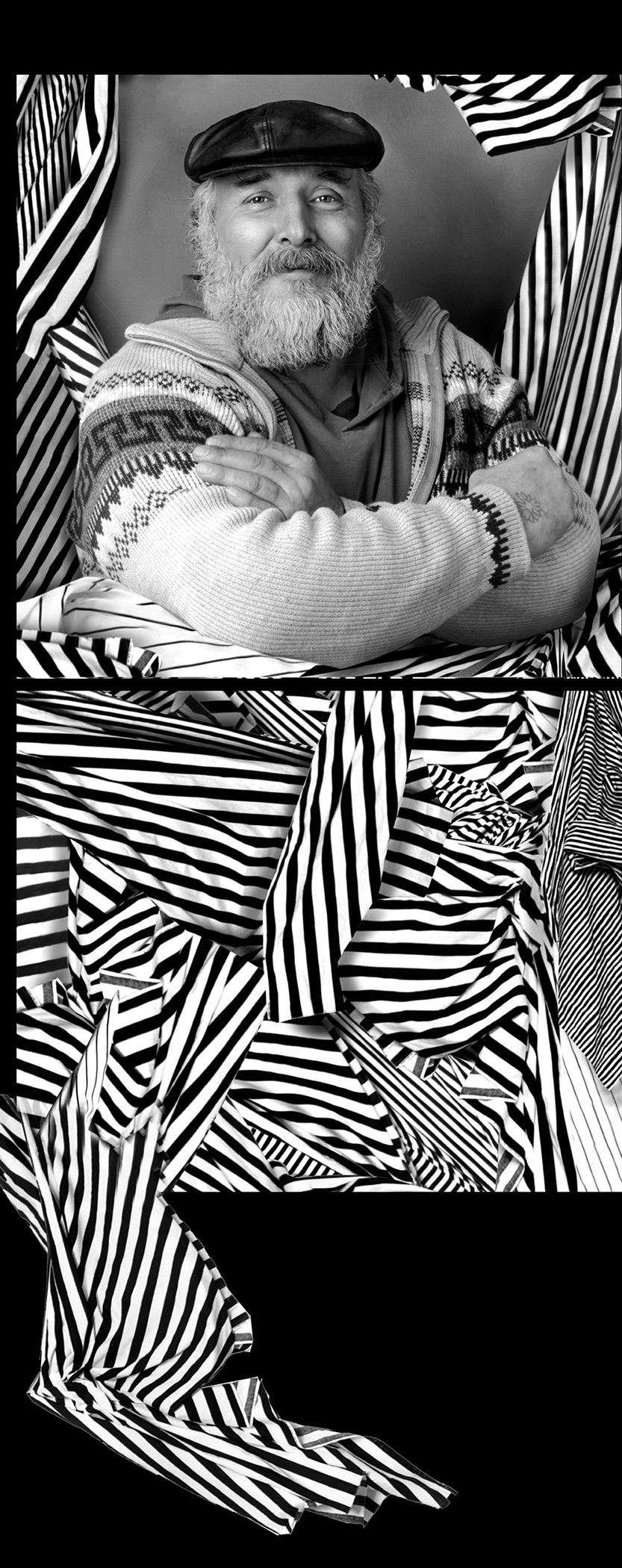

From the tiny, solemn toddlers who face the camera with curiosity to worn but dignified adults, heads cocked as though challenging fate, the faces of “Homeless in Denver,” a mural by Denver photographer John Bonath, are striking and unforgettable.

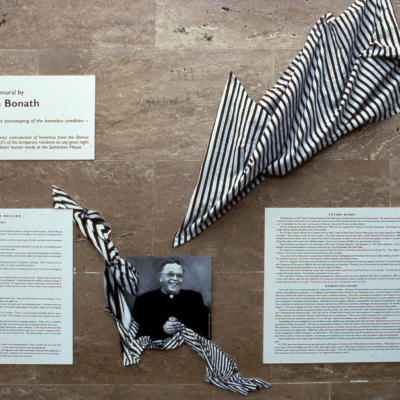

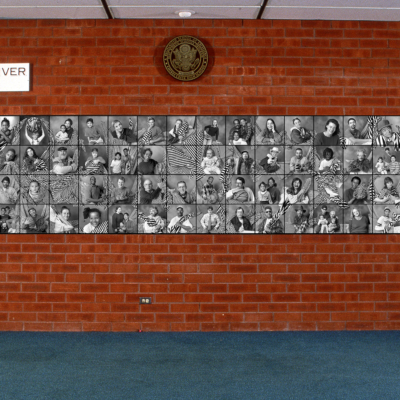

Currently on display at the Mizel Museum of Judaica before it begins touring the Denver area, “Homeless in Denver” is subtitled “Homage to Father Woody” in memory of the late Rev. Charles B. Woodrich, who founded Samaritan House and was known as Denver’s patron Saint of the homeless.

Bonath, who runs MADDOG studio, a local photography business, characterizes the mural as “a project of advocacy against stereotyping of the homeless condition. In the mural, you see all kinds of people. And the first thing (onlookers) say is that they’re surprised that all these people are homeless – that this doesn’t look like a homeless person, and that doesn’t look like a homeless person.”

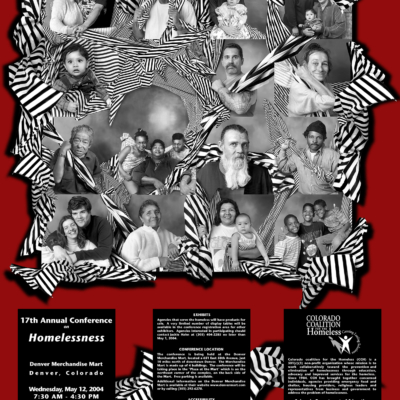

Composed of 110 people linked by artistically-arranged striped fabric, the mural was a labor of love for Bonath, who struggled for years to bring the project to fruition, assisted by various grants and the support of Father Ed Judy, director of Samaritan House.

One of the mural’s first venues was Cherry Creek High School. The mural is scheduled to tour many other schools and venues throughout the state.

“I’m hoping to use this mural as a seed,” he says, “not only to educate adults, but to also plant seeds in the minds of the youth of our society.”

The people in this mural are an arbitrary cross-section of homeless people from the Denver metro area. They represent less than 25% of the temporary residents at any given night of the year receiving food, shelter and basic human needs at the Samaritan House Shelter.

THE FULL MURAL – click sections to enlarge

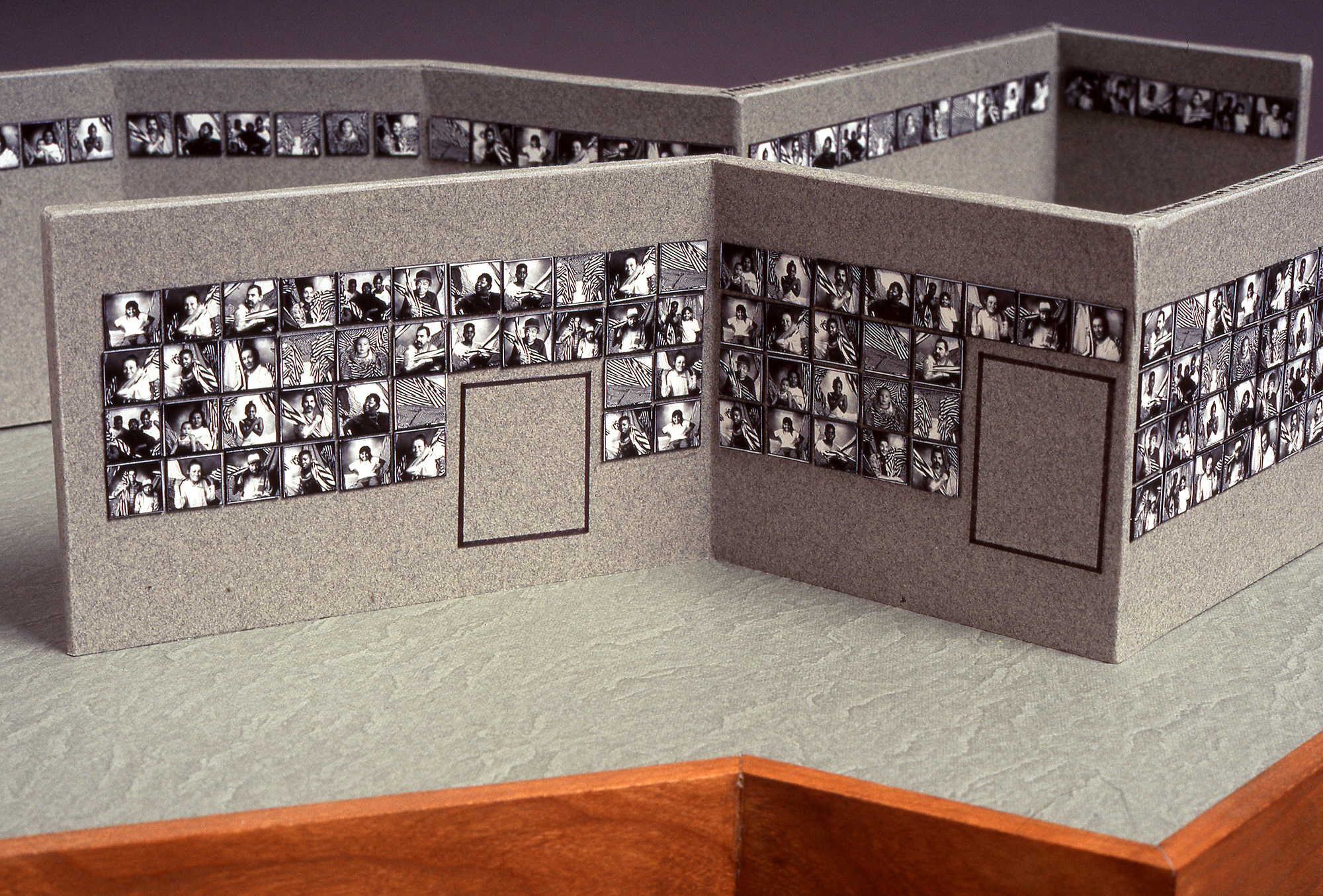

The original project was to be a permanent kiosk on the 16th Street Mall in Downtown Denver. The kiosk was to be created out of photographic-ceramic tiles and concrete. As the project evolved, it took the form of a modular mural which could tour and adapt to the different installation requirements of various venues.

PROJECT MAQUETTES

Project History

The original project was to be a permanent kiosk on the 16th Street Mall in Downtown Denver. The kiosk was to be created out of photographic-ceramic tiles and concrete. As the project evolved, it took the form of a modular mural which could tour and adapt to the different installation requirements of various venues. The mural toured throughout the state of Colorado for six years. It was installed in such places in Colorado as Arvada Center for the Arts, Cherry Creek High School, Kent Denver School, Zip 37 Gallery, Mizel Museum of Judaica, Rocky Mountain College of Art and Design, Leewood Elementary School, Columbine High School, The Art Students League, Edison Elementary School, Baseline Middle School, St. Mary’s Academy, Arapahoe City and County Building, Denver City and County Building (mayor’s office), Aguilar School, The Lincoln Center and in California at the Irvine Fine Arts Center. While in some of the schools, the mural was used to inspire student writing, poetry, theatre and dance performances. It was specifically used in this fashion to promote healing at Columbine High School directly after the massacre. In the end, the mural was retired and permanantly installed at the offices of The Colorado Coalition for the Homeless in Denver.

The Samaritan House presented John with its annual award in appreciation for his photographic support of the homeless people. Of the many stories connected with this project, John’s favorite is the story of when it was installed at Leewood Elementary School. One of the modules had fallen off the wall. A student came up to one of her teachers with beaming excitement, and exclaimed, ”I am so happy that this person has found a home!”

Artist Statement

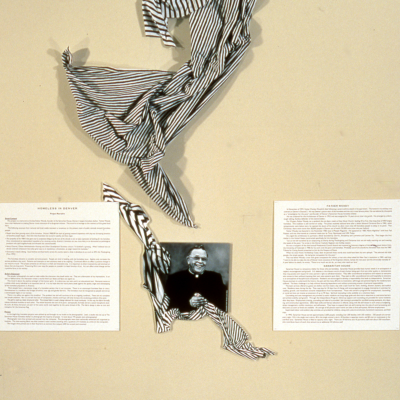

This project is a memorial to the late Father Woody, founder of the Samaritan House, Denver’s largest homeless shelter. Father Woody was a man dedicated to making Denver more conscious of its forgotten citizens. This mural is in homage to the memory of this great local hero.

The homeless situation is complex and ever-present. People are tired of dealing with the homeless issue. Apathy only increases the serious problems that exist. Patience and attempts at new solutions need to be ongoing. Continued efforts to effect a positive change in any way are crucial. This project presents an old issue in a fresh and innovative way. It is important to divert insensitivity and overload on issues that are long term. Presenting life in new ways for people to consider is a basic function of art. Art can effect social change and be a positive force in our society.

This mural expresses the positive strength of the human spirit. It is about joy, not tears and is an educational tool. Humanity exists as a whole which every individual is an important part of. It is my hope that this mural plants seeds against the apathy, anger and stereotyping of the homeless population in America.

Most people have a stereotype image of a homeless person that is not accurate. There is no stereotype homeless face or story. Homelessness is a condition that bridges all ethnic, race, age and gender barriers. The homeless must be recognized as people and not as a stereotyped stigma in our society.

There is no safety net against this condition. The problem has and will continue to be an ongoing condition. There are no complete or simple solutions. But it is certain that the loss of compassion, interest and hope will only increase the escalating problems that exist.

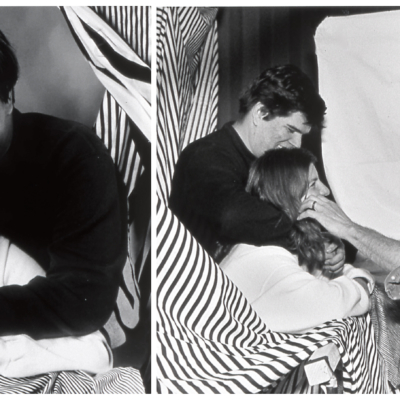

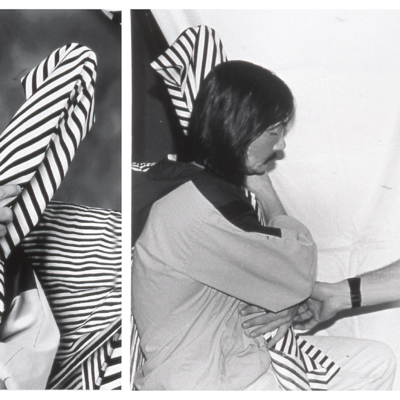

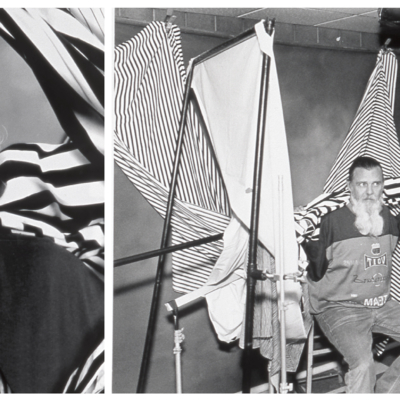

The grid in the mural is used for a basic structural order. The striped fabric functions as a design element for visual continuity. In this way the fabric formally relates individual modules to each other. The whole becomes the sum of its parts – perceptually, formally and metaphorically. As such, all these characters are part of the same world, tied together by the same thread of life. The fabric design is also an icon and metaphor for the American flag.

The mural was exhibited at museums, public and private schools, galleries and community centers around Colorado for six years before being permanently installed at the offices of the Homeless Coalition in Denver.

Process Notes:

In the beginning, homeless people were picked up and photographed at my studio. Later, a studio was set up at The Samaritan House homeless shelter to photograph the majority of people used in the mural. In total about 170 people were photographed.

The original shots included striped fabric. In the computer, these individual shots were further tied together with more fabric as the full mural was fabricated. Once the mural was completed as a single image, it was then cut up into modules for printing. The modular design of the mural is uniquely arranged for each venue that it was exhibited at.

Father Woody

In November of 1991, Father Charles Woodrich died following a severe asthma attack in his apartment. The funeral in its entirety was covered on Denver’s Channel 2. He was Denver’s patron saint of the homeless and the city’s most famous priest. He was beloved by thousands as a “streetfighter for the poor” and founder of Denver’s Samaritan House homeless shelter.

He was ordained for the Archdiocese of Denver in 1953 and was assigned for 14 years to an inner-city parish. He emerged as a blunt, tough talking, fearless defender of the downtrodden.

For ten years, Father Woody ran a sandwich line six days a week at Holy Ghost Church, feeding twenty at first but eventually the long lines grew to 400 hungry homeless people. This tradition is still carried on today. The priest received national fame after a bitter blizzard on Christmas Eve in 1982. On that night when temperatures dropped below zero, he opened the doors of his church to allow more than 60 homeless people to sleep in its pews. That Christmas, there were more than 38,000 people in Denver out of work (10,000 more than the year before).

Father Woody was featured in the November 1982 issue of People Magazine. He appeared on “ABC News Nightline” with host Ted Koppel, and was interviewed as a national media star by Time, Newsweek and USA Today.

He urged the archdiocese to purchase a block bounded by 23rd St., Broadway and Lawrence and Larimer Sts. Thus began the first shelter in the United States constructed specifically for the homeless.

“Let us not kid ourselves by an outpouring of charity during Thanksgiving and Christmas that we are really reaching out and meeting the needs of the poor,” he wrote in the Denver Catholic Register one holiday season.

He was a recipient of the third annual Presbyterial Council Award and received an honorary degree of Doctor of Humane Letters from the University of Colorado in 1986 for his work with the poor and homeless. Probably one of the awards he cherished most was the 1987 Tribute for Caring Award presented to him by the Hospice of Peace.

When his close friend, Archbishop Casey, died, he penned these words that could have been his own epitaph: “He admired the little people, the simple people. He had great compassion for the poor.”

That was father Woody, a man with great compassion for others, a man who, when asked his New Year’s resolution in 1985, said, “I want to be able to make the city of Denver more conscious of the forgotten citizens, namely the new poor and the chronically mentally ill.” A year before his death, he wrote, “There is so much we can do…so many who need our love.”

Samaritan House

Samaritan House is a temporary shelter for those who are homeless. Samaritan House provides basic human needs in an atmosphere of respect, encouragement and growth. They believe in the inherent worth of every human being apart from any other quality or characteristic they may possess and respect for every person’s right to self-determination. They offer unconditional acceptance and respect to everyone who comes to them without imposing their own value systems upon them. They seek to offer unconditional love and hospitality to everyone in an atmosphere of discipline and compassion. Residents are encouraged to develop a responsibility that leads to independence. Samaritan House attempts to understand the history, the pain and the many affronts to motivation, self-image and personal dignity the residents have suffered. The basic challenge is to help without fostering dependence and without promoting evasion of personal responsibility.

The basic services offered to guests are shelter, two hot meals a day with a sack lunch for work, clothing, showers, laundry, and medical care. Residents leave during the day. They may stay for 30 days free of charge with encouragement to engage themselves in activities for stability, growth, and movement towards independence from homelessness. Those who enroll in programs for employment, counseling, or social services can receive an extension of up to 90 days. Spiritual counseling is also available on a voluntary basis.

Counseling and case management are provided to assist residents to set long-range goals and short-term objectives to overcome barriers and achieve stability and growth. Through the Independence Program, follow-up support and counseling are provided for some residents after they leave. Employment training, counseling and referral is provided. Job training is provided for certified nursing assistants, dry cleaning, and construction apprentices. GED/basic skills and literacy education is offered, along with life skills classes in such areas as budgeting, stress management, conflict resolution, and self-esteem. An average of 65 persons each month are able to find permanent, full-time employment.

Supervised indoor and outdoor play activities are provided for children, along with cultural enrichment, homework assistance, and field trips.

In 1995, Samaritan House served approximately 2,600 people, including over 200 families with 350 children. 330 people are served every night; 124 in the single men’s dorm, 48 in the single women’s dorm, 20 families in separate rooms, and 80 men on mattresses in the overflow area. Samaritan House is filled to capacity every night. There are 30 full-time and 10 part-time staff with about 350 volunteers who contribute hours of work that amount to an additional 30 full-time staff.