Stories from the Hood, Part Five – The Tunnel

Stories from the Hood

The Tunnel

Chapter Five

A walk through the neighborhood is always an adventure. I stuff my pockets with poop bags and hook up two excited balls of energy to their leashes ; as we connect with a common consciousness, my lower vertebrae begins to wiggle. We are going for a walk in the hood. With an open attitude, we head into the realm of the unknown. Although our route is an old friend, the encounters that await are rarely predictable. The plan is usually the same: to the end of the street, under the highway, then to the river and back. The railroad tracks and a pedestrian walkway go under the highway connecting this residential neighborhood to the parks and rivers on the other side. The worlds on each side of the underpass are much like different planets, making the walk under the highway a bit like going through Alice’s rabbit hole. The tunnel is a dark, magical, and an instinctively vulnerable place where, for a moment, any feelings of security dissipate. Most hurry through this passage and do not linger. Immediately upon exiting the dark tunnel, the harsh radiance of the Colorado sun blinds your eyes for a moment, warms your skin and the temperature rises by a full ten degrees.

Above the entrance to the tunnel is the first panel of the “Neighborhood Epic” murals. In this history-of-the-neighborhood sequence, the first panel depicts the prehistoric era of dinosaurs and documents their extinction when the great meteor collided with Earth. With this picture marking the entry into the tunnel, it is fun to fantasize the tunnel as a worm-hole in time with dinosaurs grazing on the other side.

The human element is always part of the scenery on an urban walk. When it rains at night, the tunnel offers shelter for marginalized people to sleep ; in the heat of a summer’s day, a cool place to hang out. Sometimes I end up in a homeless encampment, sometimes sitting in the shade of the tunnel exchanging life stories with a stranger, and sometimes trying to capture a character in a photograph. The tunnel can be counted on to yield something of interest with each new day.

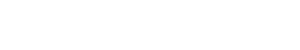

As we begin our walk, I notice things I have never seen before: a new weed, an interesting piece of trash, a new crack in the sidewalk. All are messages of some kind from events that have come and gone, events to be read from evidence left behind in time ; the combed grasses along the river tell the story of yesterday’s water currents ; clothes strewn about from an abandoned flight bag engage the imagination ; amidst the sound of passing trains, a makeshift bed gave a warm body some much-needed rest ; a deck of playing cards strewn on the railroad tracks will be missed when a train hopper’s pocket is discovered to be empty ; a used condom and an empty whiskey bottle ; Goliath wind-generator propellers strapped on a train bed are on their way to the Wyoming wind fields. I notice a neatly folded dollar bill in the gutter and wonder where it came from as I carefully put it in my pocket ; in a freshly scraped lot a new house will soon evolve ; a flattened bag is fodder for a new photograph as it becomes a spaceship on a spiritual voyage ; leaves on the sidewalk become a painterly study ; a spilled box of Crayola crayons catches the eye. Everything whispering its story, waiting for someone to listen, teasing the imagination, and propelling me into a perpetual state of wonder.

As with beach combing, sometimes that long anticipated treasure appears. I notice something stuck in a bush outside the tunnel that looks like a rotting, dead animal skin. I hesitate to actually check it out – like all the others passing by – but my curiosity and fascination get the best of me. Slowly, I turn it over with a stick, expecting maggots. Much to my amazement and joy, it turns out to be a highly realistic mask of a growling wolf’s head. It feels like a gift bestowed on me by the cosmos; my mind races with possibilities.

At the time, I was working on a photographic series called “The Forest” in which I was building forests in my studio. I thought of my new-found treasure as the head of Little Red Riding Hood’s wolf ; a story I could bring to life In my fairy tale-like forest. Synchronistically, I ran into a homeless man who wanted to model for me and with little effort, the two came together.

As you exit the other side of the tunnel, there is a vast unkempt field on each side of the sidewalk. When in season, this field is filled with wild sunflowers. At such times, the bright yellow sunflowers are reminiscent of a Van Gogh sunflower field or the poppy field surrounding Oz (with the island of Denver’s skyscrapers visible in the distance). When the wild flowers are in bloom, this field manages to attract the city’s butterflies. When I emerge onto the path through the sunflower field and see a butterfly, my thoughts transport me to childhood memories.

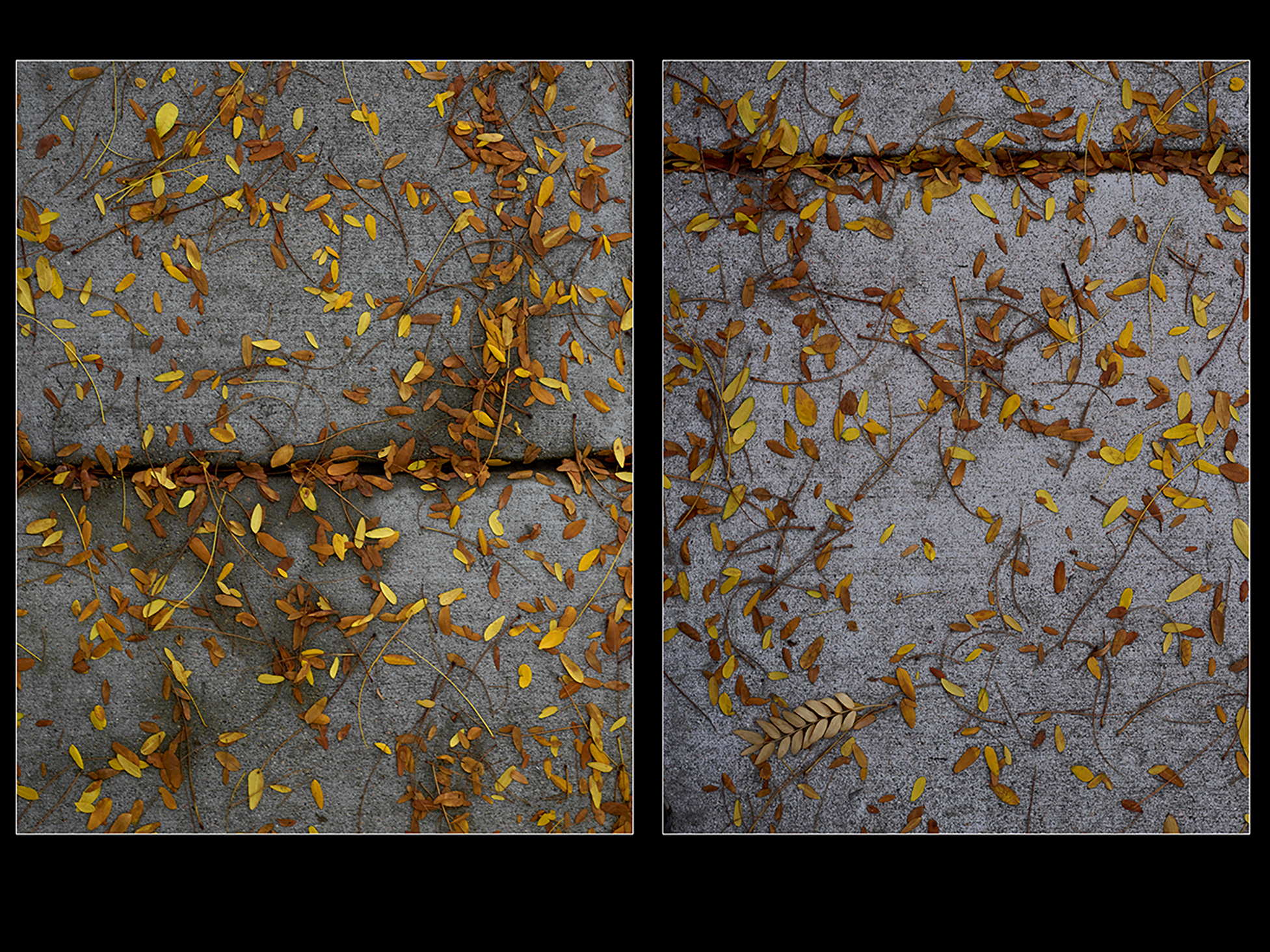

During adolescence, I was an avid butterfly collector. I carried my home-made butterfly net with me most of the time in a state of perpetual readiness for that chance encounter. My mother saved Peter Pan Peanut Butter and smelly pickle jars for me to euthanize them in and my father built beautiful glassed shadow-box cases for their display. My butterflies were spread and dried in “specimen position” with a vast assortment of pins and paper strips, then labeled. I knew all the butterflies by name and had my favorites. Their descriptive names conjure up poetic visions with such story-like attributes as painted ladies, admirals, viceroys, dukes, emperors, gatekeepers, satyrs, black witches, comets, gypsies, peacocks, midgets, dingy skippers, and morning cloaks. Moths are the butterflies of the night and have names from Greek mythology like Polyphemus (the one-eyed cyclops), luna (goddess of the moon), and cecropia (half man, half snake). The magnificent yellow tiger swallowtails were in great abundance and the zebra swallowtail was the rarest of them all. The zebra was the missing piece in my collection, like the glaring empty spot in a coin collection. My thoughts return to the present as I realize I do not have a net on me. For the moment, I am content to catch a glimpse of these winged wonders, remember their names as they fly off, and proceed on my walk.

On the other side of the tunnel, the milkweed plant grows by the river. This plant is what the monarch caterpillars feed on. As I check to see if there are any signs of monarch caterpillars, my thoughts again return to my youth. I remember raising caterpillars and tending their cocoons and pupae. During winter months, I put drops of water on many a cocoon for cecropia, luna, and Polyphemus moths. Then in the spring, I watched them emerge transformed to flap out their wings in my bedroom. My favorite chrysalises were the monarchs; they were clear and over the course of a winter, you could witness the morphing process inside as they went from a gorgeous green to brilliant orange and black with silver dots. The monarchs are special as they are the only butterfly to migrate. In the fall, they migrate across the continent to congregate in one spot north of Mexico City and another in California. When the monarchs are passing through Denver on their way south, they can be seen in unusual numbers on the other side of the tunnel.

In my art, butterflies are metaphors for the human spirit. The migratory nature of the monarch, especially, embodies the idea of a migration of the spirit. Once I had the experience of a lifetime while visiting friends in Bolinas, California. I just happened to be out for a walk and by pure chance, stumbled into the Audubon Monarch Groves. In this small area, there were more monarchs on the giant Eucalyptus trees than trees have leaves, their brilliant orange wings shimmering in the golden California sun against the deep blue sky. They were lined up on the electrical wires body-to-body. Cars had hit so many that the ground was covered with a thick carpet of their brilliant orange color. All around, they swarmed in the air, landing all over your body and tickling your skin with their tiny feet. The following artwork with butterflies includes a photo-silkscreen from that day in Bolinas.

Butterflies appearing in my work over time. In the “Angels” series they are a metaphor for the migration of the human spirit.

We homo sapiens are a species of hunters. Civilized and primitive societies alike have a need to satiate this instinct. The primal response to spotting and stalking a butterfly with net in hand is not all that different from chasing a buffalo down. Having but one chance to swoop it up, with perfect technique, produces a momentary high that is addicting. These days, I don’t act out my hunter instincts with butterfly hunting but do so through photography. In lieu of a net, I use my camera to catch the spirit of things around me. The camera is often thought of as hunting with such gun-like terms as loading the camera, shooting, a shot, snapshot, machine gunning, trophy shots, pistol grips and flash guns. When I go for a walk with camera in hand, it is much like going on a butterfly safari with my net. I am out to capture spirit in my camera and bring it back. As an artist/hunter, my studio walls abound with a mix of specimens from nature and photographic works, all for study and inspiration.

Butterflies being spread in position for some photographic ideas.

A couple shots in my studio.

The Butterfly Collector, a daguerreotype circa 1850 by an unknown photographer.

Photography (Greek for“light drawing”) is the interaction between light and light-sensitive materials. On one hand, it is little more than that; but on the other hand, light is the most magical element in the universe. Catching light with a camera is nothing less than a miraculous phenomenon. As a photographer, going for a walk is always a submersive experience into the realm of light. Always aware of the qualities of light, I visualize in my mind’s eye what kind of photograph the light around me might render. I am always notating the way certain kinds of light might manifest in an image and create a feeling that emanates from within the photograph. There is always one place on my walk that stops me in my tracks to simply admire the light. That place is the tunnel.

Underpasses like these have a special way in which they transform light. Like a tube, the sunlight enters from both ends rather than coming from above, as we are accustomed to. Any given point in the tunnel offers different lighting options. Shadows follow suit with the light as they dramatically define and fall obliquely off forms onto the simple concrete wall background. When I approach the tunnel with my camera, it is like checking out my “light trap” to see if anything is inside it today to harvest with my camera.

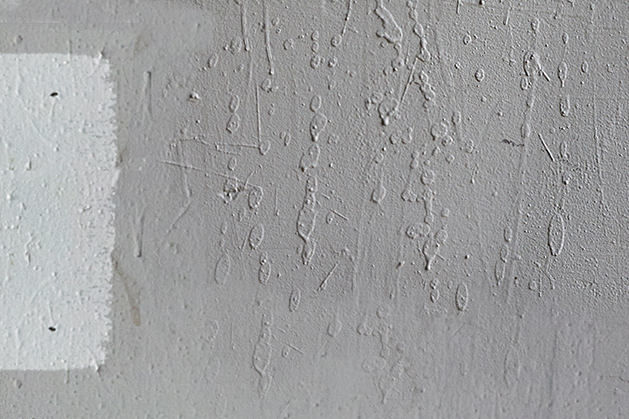

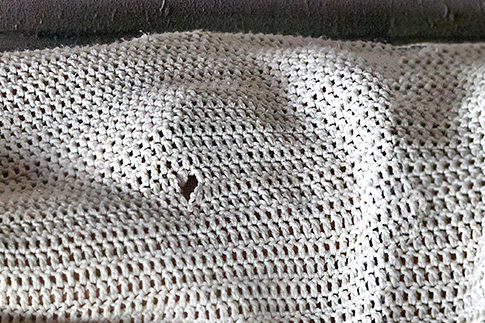

The following image of a sleeping man was shot in the tunnel ; his face lit from below, the texture on the pillowcase and blanket coming out strong from the oblique angle of light, the glow of ambient gold light bouncing off the beer can and coloring the concrete, the gossamer sheen on the white paint, the radiating glow of blue light coming from some fluid inside the bag on the right, and the extreme lunar-like texture of the wall and floor.

As I was passing this body, I was immediately reminded of a painting that hangs in the Museum of Modern Art by the painter Henri Rousseau entitled “Sleeping Gypsy”. In this painting, the sleeping man’s body and dark face is similar and next to him lay objects that tell of his life. Above him is a full white moon – much like the bright white square hanging over the man in the tunnel. In Rousseau’s painting there is a lion standing on top of the sleeping man. I couldn’t believe it when I noticed the man was sleeping on a blanket with a large tiger on it. I photographed the man as he lay there while joggers and a mother with a baby carriage passed between us. I photographed him in a grid of nine photographs. Later, these nine pieces were spliced together in the computer to form a single image. In this way I could “unfold” the picture, as in Rousseau’s painting, so that the man was laying on the horizon line and almost falling off a tilted picture plane. Shooting it this way also enabled me to create a mega-high resolution file that could be printed extremely large while maintaining sharp detail.

The allegorical aspects of this image are profuse. The colors between the cracks in the wall tell of layers of graffiti that have been rolled over by layers of gray paint, like a subtractive printmaking technique. Cigarette buttes catch light from within the deep cracks; a freshly eaten banana peel is lit with its long shadow at the man’s feet ; hot-pink graffiti drips come off the stenciled “no camping” sign as the man sleeps below in direct violation of law ; white rectangles cascade down from the top into the white rectangular pillow holding the man’s head ; and a very mysterious hole above the man’s head beckons interpretation, perhaps it is a door to his dreams or perhaps a rat’s nest. All the details, describe in a visual language, the story of this moment in a man’s life. My intention being to simply portray the beauty of this human scenario with compassion.

The next day, I ran into this same man outside the tunnel. The police had just ruffed him up and tossed all his possessions from the shopping cart onto the sidewalk. He was visibly shaken, and angry, as he gathered his worldly belongings to put his life back together in the cart.

“Did you get the money I left in your shoe yesterday?”, I asked as I approached him.

“I did, so that was you. Thank you.”, he replied, as he started to relax a little.

“Did you know I took a picture of you sleeping in the tunnel?”, I added.

“I thought I heard your camera clicking.”, he said with a grin.

“Would you mind if I did a portrait of you now that you are awake?”, I asked.

He said, “One minute the police have no respect for me as a human being and treat me like scum, the next minute a stranger like you shows me respect. What a crazy world. Maybe there is hope after all. I am honored that you would want to take my picture.” With that, I did the following head shot and a long running friendship began. It has been over six years now. I still run into him and occasionally he rings my doorbell to say hello. As it turns out, he was born in the row-house directly across the street. His mother now lives down the block and he drops in on her now and then to take a shower. This is my special friend Marci.

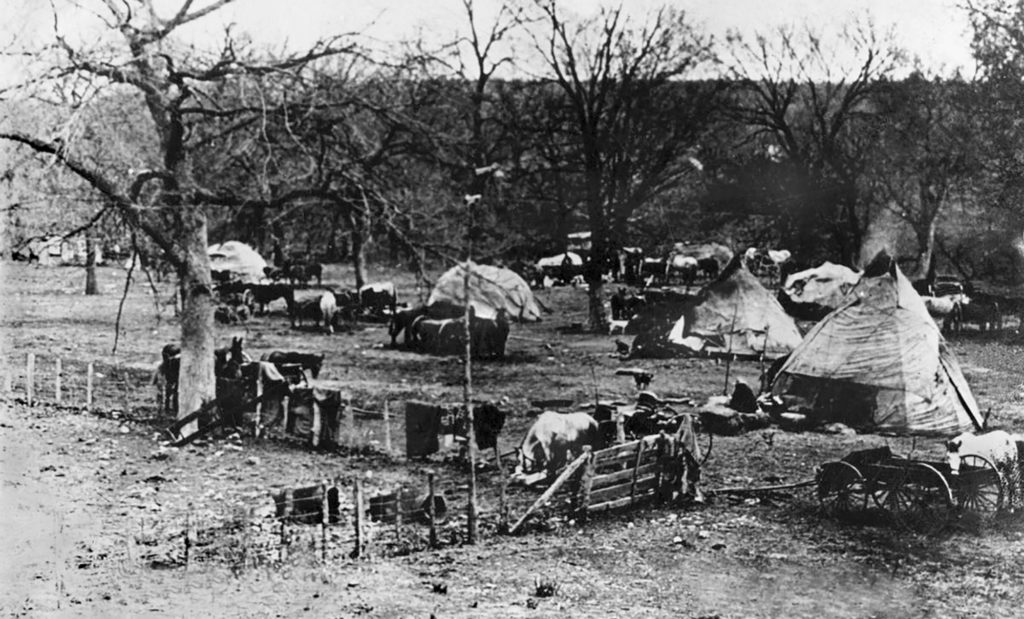

Train-hopping has a very rich and romanticized history. Even Ernest Hemingway did a little. In the United States, this was a common means of transportation following the American Civil War as the railroads pushed westward, especially among the migrant workers who became known as “hobos”. It continued to be widely used by those unable to afford other transportation, especially during times of widespread economic dislocation such as the Great Depression. Although the practice is less common today, a solid community of freight-train riders still exists. Rail companies have their own private police departments whose goal it is to deter and exterminate train hoppers. These railway security men are known as “bulls”. The Amtrak Police is the largest with more than 450 sworn officers who undergo training alongside other federal officers. They are armed with Glock 22 .40-caliber pistols and no less than 100 5.56mm Bushmaster Patrolman’s carbines and batons. The bulls and brakemen are infamous for the beating and maltreatment of the vagrant population. Because railroad companies can only patrol stopped trains, freight-hoppers often embark and disembark while the train is in motion to avoid the bulls. But freight train cars are not designed for human riders; hopping on and off moving trains bears serious risk of dismemberment or death.

With all the railroad tracks that go under the highway, the tunnel is a good place to run into this special breed of people. One train-hopper I met showed me some odd graffiti in the tunnel. He said it was written in “train-hopper code” and communicated information about the “bulls” in the area. This train-hopper graffiti also relayed information on good places to hide and wait for trains. I couldn’t really decipher the graffiti any better than the bulls, but the train hoppers seemed to understand it quite well.

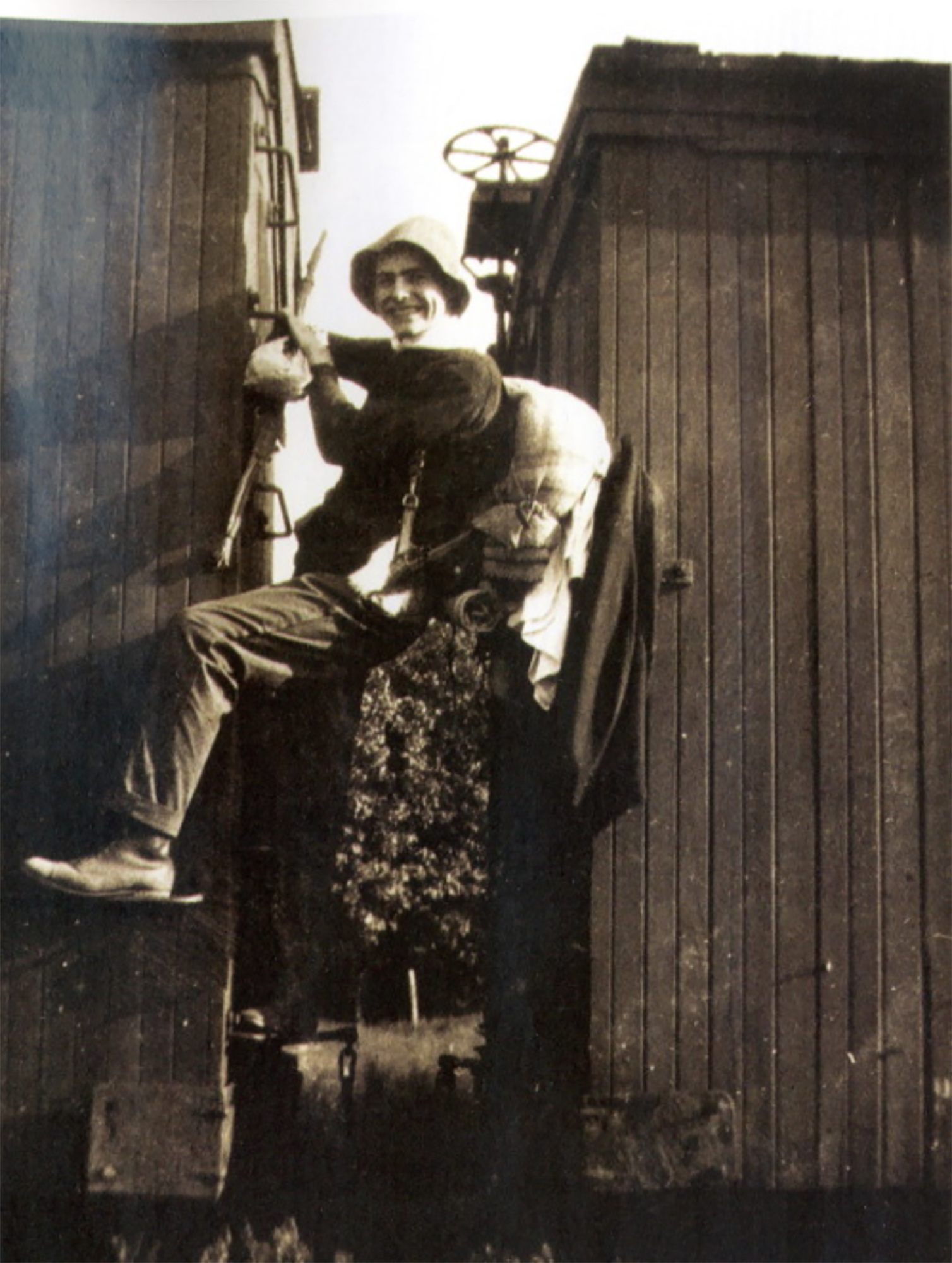

Young Hemingway train-hopping

The train hoppers are my favorite demographic of the homeless population. They are a free-spirited breed, always on the move from place to place, like butterflies hopping from flower to flower as it suits them and drifting where the wind blows. They thrive on their carefree freedom. They also seem to have relatively lucid brains, as the absence of alcohol or drugs during travel is imperative. Many are young and physically able to manage the train-hopping lifestyle, and there are the older veterans, many of whom are ex-cons. I even run into hoppers resting at the tunnel that have adopted a stray dog or cat found along the way. Apparently hopping with animals is do-able and the bonding and companionship benefits apparent.

Train hoppers at the tunnel.

Philly and Lyric are self-proclaimed “punk-gutter homies” (the permanent, lifelong homeless) . Philly is 35 and has been homeless since he was 12. He smokes meth and marijuana every day to “manage his illnesses”. Lyric is 25 and has been homeless since he was 12 as well, when he fled domestic violence. He was inspired by a video game to make this weapon out of wrench. He demonstrated how it is used like a ball on the end of a chain in lethal battle. He asked me to photograph his dirt encrusted hands.

In the tunnel, there is a wire-mesh fence separating the walkway from the railroad tracks. A hole has been made in the fence that most train hoppers and the homeless use. It appears like an entryway to another world. The light is beautiful there and the design of the bent wire mesh is very sculptural. The following are a few photos I took at this special passageway in the fence: an abandoned homeless sign ; Ookie rolling a cigarette ; Ookie pulling his bandanna over his face ; some oranges that someone left in kindness; and some shoes left for feet in need to try on.

The hole in the fence.

On my return home, I exit the tunnel and am back on the hood’s residential streets. The streets in my hood are part of a grid-work of alphabetized names and numbers crossing each other. The street names defining my hood have a tribal vibe to them, like a fiefdom.

My house sits on Osage Street, one line amongst alphabetized street names that mostly consist of Indian tribes. The street names include: Inca, Jason, Kalamath, Lipan, Mariposa, Navajo, Osage, Pecos, Quivas, Raritan, Shoshone, Tejon, Vallejo, Wyandot and Zuni. Jason and Quivas are not Indian names. Jason comes from Jason and the Argonauts of Greek mythology, and was used in lieu of anything logical because a “hard J” was thought easier to pronounce in the English language. Kalamath is probably supposed to be Klamath. Mariposa probably stands for Mariposan and Vallejo is the name of a place.

None of these Indian tribes actually lived in Colorado. The native American tribes that occupied Colorado were the Apache, Ute, Cheyenne, Comanche, and Arapaho tribes. This is the panel of the Keating/Luna Neighborhood mosaic depicting those times before the settlers moved in and took over this place we call Denver.

It was in 1897 when the Denver Water Company hired Henry Maloney, a bookkeeper and Indian agent, to organize Denver’s street names. It was mostly due to a large number of complaints about billing and service issues with customers. He realized that the Denver street name system was preventing the water department from finding customers. The same was true for the police, fire, and people always getting lost. The patchwork of names was due to developers having the control in naming streets. Most street names were only blocks long and changed rapidly. Every community had different street names. Imagine Speer Boulevard changing names every two blocks. So the city figured out a system of grids with numbers and alphabetical names. It was up to Maloney to come up with the names.

He came up with my neighborhood names. Maloney chose names he figured were phonetically easy for people to say. At the time, many citizens protested the Native American street names. Some newspapers even said the move was “honoring ‘savages.’” But the names stuck.

The Osage Indians, of my street name fame, have one of the most bizarre chapters in American Indian history. I am surprised that Hollywood has not latched onto this amazing story. Based on the story alone, it could walk away with all the awards. But for now, I will relay this tale to you in my humble blog. The Osage had the usual tragic stories of multiple government relocations but with a most unexpected and bizarre twist. The best account of this drama comes from David Grann’s book, “Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI”.

The Osage Indians were originally located in Missouri by the Osage River on 100 million acres of land. They were herded onto a reservation in Kansas that was 50 by 125 miles in size and told by the government that this land was theirs forever. Awhile later, the government compensated them $1.25 an acre and re-relocated them. This time onto the most barren and rocky portion of northwestern Oklahoma – out of sight, out of mind. This “worthless” land, as it turned out, was sitting above some of the largest oil deposits in the United States. To extract that oil, prospectors had to pay the Osage for leases and royalties. In 1923, the Osage received collectively what would be worth today more than $400 million. Many of the Osage lived in mansions and had chauffeured cars and servants.

Wealthy white America, stoked by racist and sensational press, went into a moral panic. Newspapers told exaggerated stories of Osage who threw out grand pianos on their lawns or replaced old cars with new ones after getting a flat tire. Harper’s Magazine wrote, “The Osage Indians are becoming so rich that something will have to be done about it.” Something was done about it.

It was said that, whereas one in eleven Americans owned a car, every Osage owned eleven of them.

The federal government monitored the Osage Indians’ spending habits by appointing white guardians to oversee and “help” them spend it. Even small amounts of money had to be authorized for spending. Graft was out of hand. Then things got worse. The Osage began to die under mysterious circumstances. They were, as a newspaper of the time reports, “shot in lonely pastures, bored by steel as they sat in their automobiles, poisoned to die slowly, and dynamited as they slept in their homes.” Few if any of these crimes were solved. In the lingo of the time, who cared about, a “dead Injun”? It went on for so long because many people were part of the plot – lawmen, prosecutors, reporters, oilmen, even morticians who buried the bodies and doctors who helped give the poison.

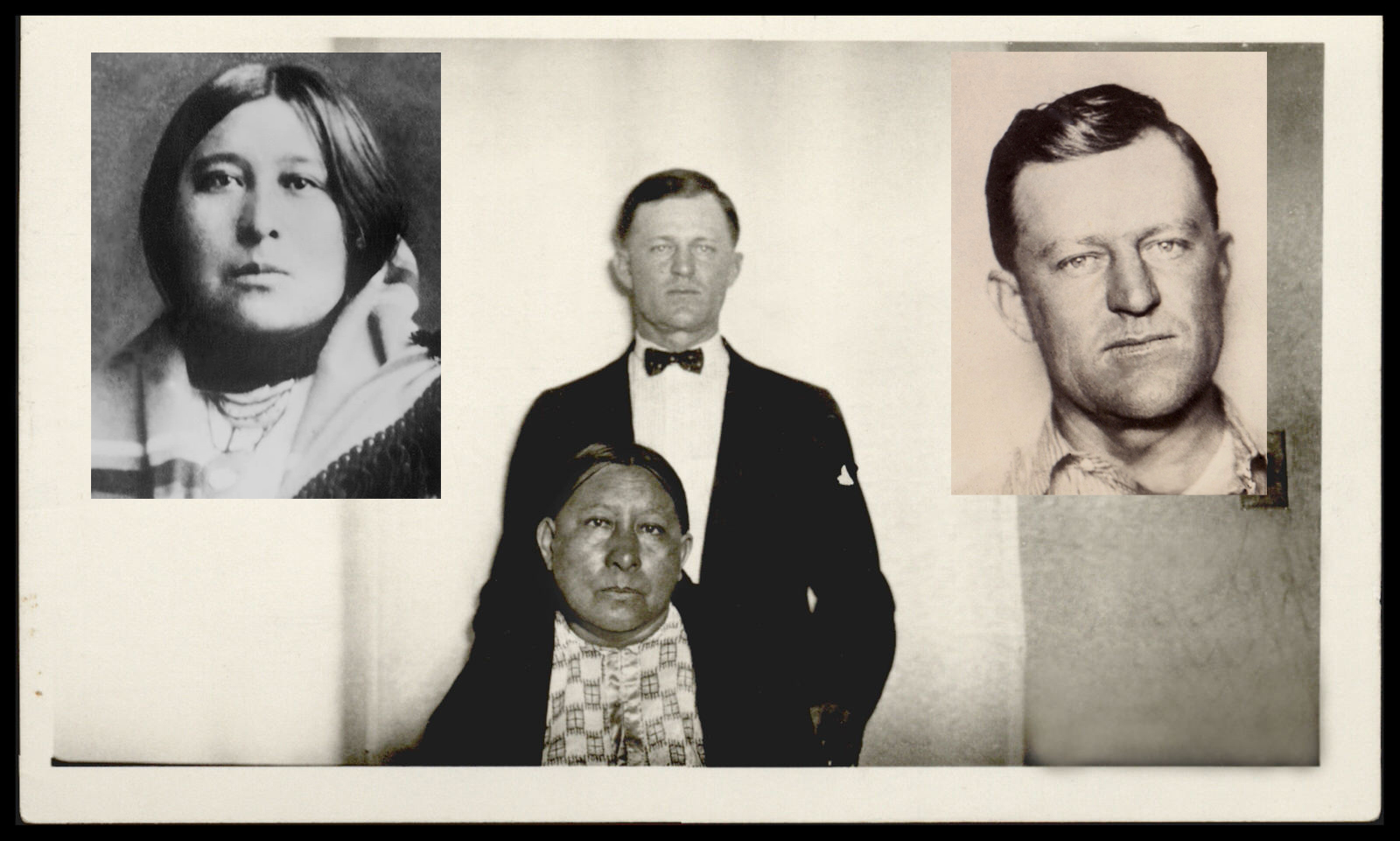

The plan was so sinister that it involved marrying into families. There was an evil level of betrayal and calculation to the very people they pretended to love. After a white married into an Osage family, the family began to die. One in particular, Mollie Burkhart, married the nephew of “The Kind of the Osage Hills”, the ringleader of this conspiracy, William Hale. Hale directed his nephew, Ernest Burkhart, to marry a wealthy Osage woman named Mollie, so that over the next couple years, he could begin to kill her family members and take their wealth. Thus the family of Mollie Burkhart, became a focused target. In the spring of 1921, Mollie’s older sister, Anna, disappeared. A week later, Anna was found in a ravine decomposing, shot in the back of the head. Then Mollie’s mother became ill and died ; she had been slowly poisoned.

When their tribe struck oil in the 1920s, Mollie Burkhart and her family became some of the wealthiest people in America.

But they were soon the target of a ruthless campaign of murder by William Hale.

Mollie’s younger sister was so frightened by these killings that she moved with her husband closer to town. Their house, where a maid also lived, was not far from Mollie’s. Late one evening in March 1923, Mollie, her husband, and their children were woken by a loud explosion. She got up and went to her window and looked in the direction of her sister’s house to see an orange ball of fire rising into the sky. Somebody had planted a bomb under her sister’s house, killing the couple and their maid.

Those who tried to catch the killers or investigate the killings were also killed. One good Samaritan attorney was thrown off a speeding train; another oilman got as far as Washington, D.C. only to be found naked, stabbed more than 20 times and his head beaten in. The entire tribe went to the federal government, beseeching help at a national level. In 1923, an obscure branch of the Justice Department, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, was assigned to investigate. They initially sent out, Blackie Thompson, a notorious outlaw himself, hoping to use him as an undercover informant. But unfortunately, instead, he seized the opportunity to rob a bank, kill a police officer and was gunned down himself. Meanwhile, the Osage tribe was getting picked off one by one by a large and organized group of racist serial killers.

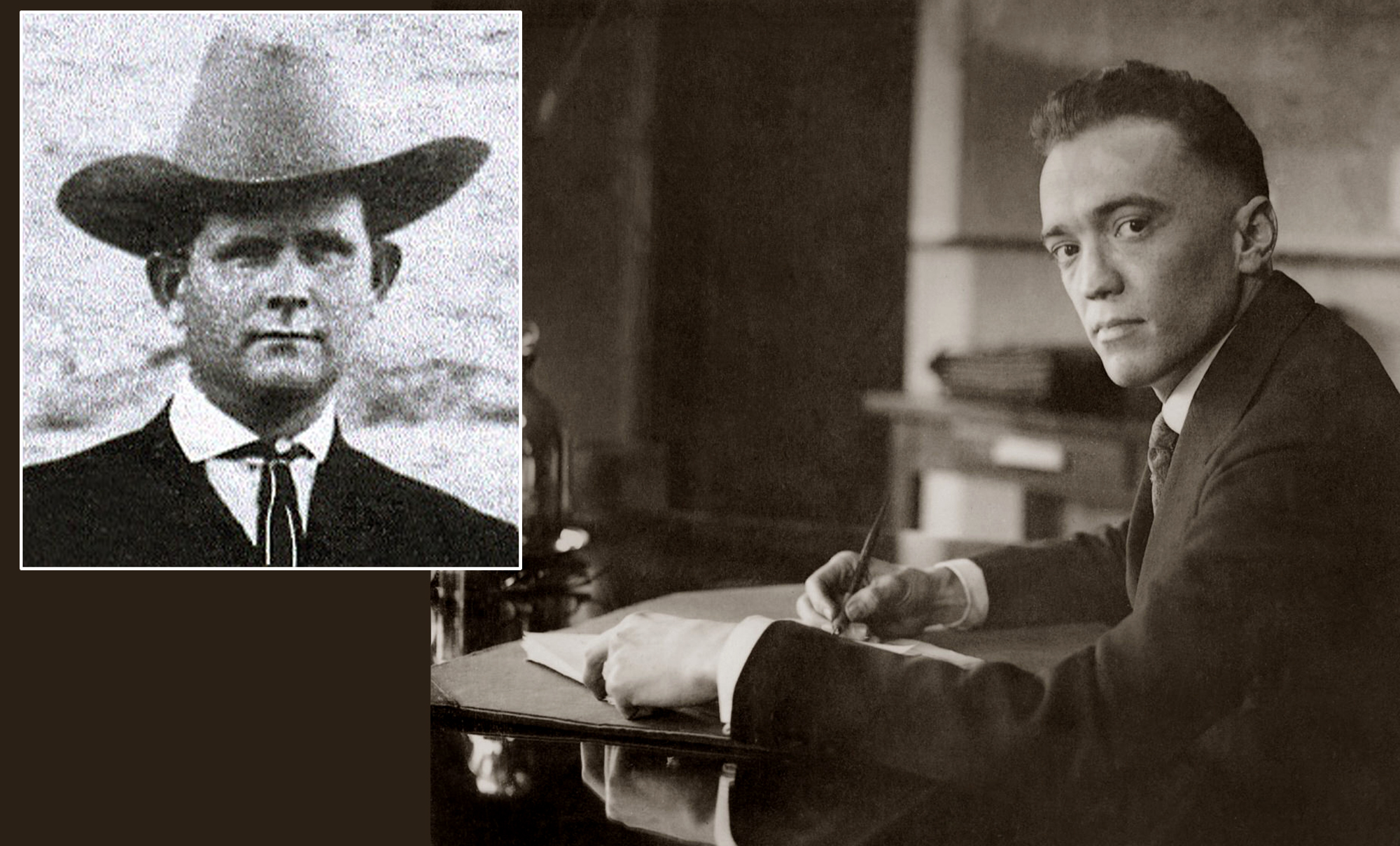

J. Edgar Hoover was only 29 when he was appointed the acting director of the FBI in 1924. He was out to build a bureaucratic kingdom for himself and feared the botching of the Osage investigation could undermine his dreams. Out of desperation, in 1925, he brought in a field agent named Tom White to take over the case.

Former Texas Ranger, Tom White, had what it took. It was dangerous work. White had nerves of steel and a demeanor of iron like Henry Fonda in Twelve Angry Men or more recently like Agent Cooper in David Lynch’s TV series Twin Peaks – only with a factual plot stranger then fiction. White gets his man, a local cattleman named William Hale and a figure of genuine evil. White put together his own undercover team, including an American Indian agent. One of the agents posed as an insurance salesman, others pretended to be cattlemen. By following the money to see who was profiting from the murders, White and his team were able to capture some of the killers.

William Hale and Mollie’s husband, Ernest Burkhart were convicted, but it was a culture of killing which eliminated several hundreds of Osage Indians. Most of the killers and murders were never investigated. The “financial mentors and guardians” and the corresponding Osage they were assigned to are recorded in a government ledger. Most of the Osage who had a white guardian to help them manage their funds eventually ended up being listed as “dead” in the government ledger books. It is of note that my street was named a couple decades prior to the tribe striking it rich in the 1920’s. Such is the legacy behind my street name.

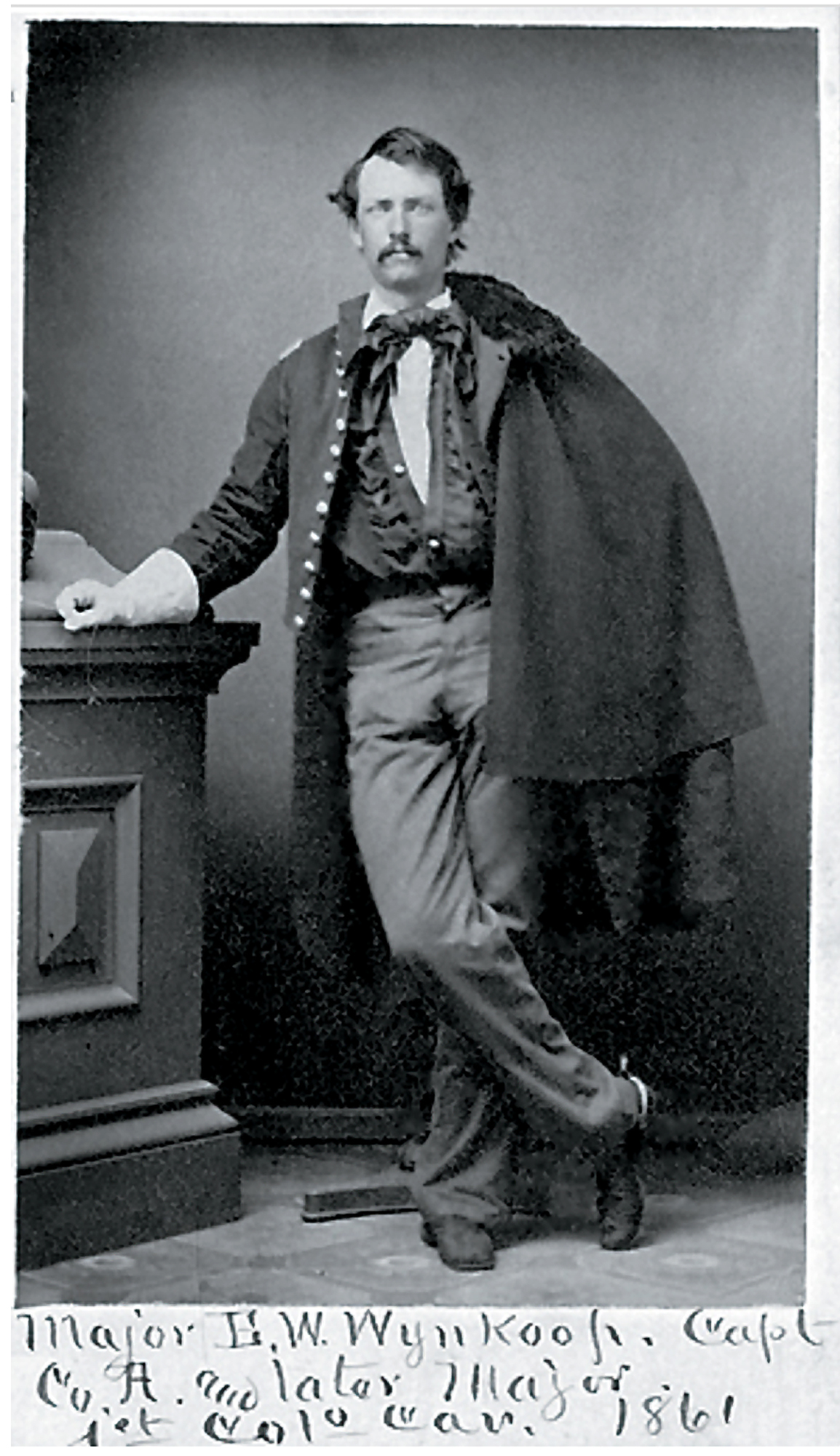

Denver’s streets offer an encyclopedic history into the past. Many of the names memorialize colorful characters, leaders, and Colorado legends who forged Denver’s history. In my research on Osage Street, I ran across another well known street close by with an interesting character behind its name. Wynkoop Street, in front of Union Station, was named to honor Edward Wynkoop.

There is a plethora of history to be found on Edward Wynkoop so I will just highlight a couple of my favorite stories. He moved out here in 1860, just prior to the Civil War. He was a sheriff with an independent mind and a Yankee’s point of view. One day, the postmaster, McClure, refused to hand over Wynkoop’s correspondence until he paid the $5 he owed for mail services. Wynkoop simply grabbed his letters and walked off with the postmaster screaming at his back. They were initially best of friends, but McClure was a Southerner and they had major political differences. When they met later, McClure cursed out Wynkoop again. You would think their friendship would have been worth more than $5, but that was not the case. At that point, Wynkoop was not going to pay up or put up with more cursing. It was still the “Wild West” back then and ignoring the fact that dueling was illegal, Wynkoop challenged McClure to a duel in order to settle their differences. McClure accepted the challenge.

They scheduled the duel for January 2nd, 1862. The day before the showdown, McLure sent a mutual friend to tell Wynkoop that he “could hit larks on the wing.” Wynkoop smirked and retorted, “Larks don’t have guns.” The sheriff then walked the streets of Denver, firing his guns at selected targets. He hit targets the size of silver dollars at up to 60 paces. Crowds gathered to watch, cheering each shot. When Wynkoop spun around and hammered a heart drawn on a tree, an onlooker cried out, “Thank God, I am not a gentleman.” The gamblers mostly placed odds against McLure’s chances the next day. During Wynkoop’s flashy shooting exhibition, no one dared confront him. After witnessing the sheriff’s marksmanship, one woman rushed to McClure and told the postmaster, “You’re a dead duck if you face that Kansas jayhawker.”

When Wynkoop arrived at the field of honor the next day, he was all deadly business. As their seconds went over the rules, McLure realized his friend-turned-foe was not about to chicken out. Some 1,500 people, including an undertaker, had gathered near the Catholic church to watch the two have it out to the death and place their bets. McLure’s confidence waned; he had an epiphany that he was not ready to meet his maker quite yet – or you could say, he chickened out big time. With the clock ticking, the postmaster apologized to Wynkoop, handed him his mail and offered him a year’s free postal service. Since Amazon, FedX, and UPS were not options back then, Wynkoop accepted the offer from USPS and let McClure lick his stamps.

Wynkoop lived by his own set of rules and stood up to many a confrontation in his life. While true to his country, he walked his own line and had no fear of taking an unpopular stance that would garner him enemies. This independence was unwavering and served him well later in the Army. Neither Sheriff Wynkoop nor Officer Wynkoop would tolerate compromise. He had full trust in his viewpoint and always acted upon it – consequences be damned.

Four years later, in 1864, he was in the national spotlight when he was involved in a clash with the Cheyennes in the Colorado Territory. Major Wynkoop, of the 1st Colorado Volunteer Cavalry, did what he thought was right. He met the warring Indians, received four white child captives, and brokered seven Cheyenne and Arapaho chiefs to Denver to discuss ending the conflict. It so happened he had acted without orders and was removed from command.

With Wynkoop out of the way, a troupe of Colorado volunteers attacked mostly peace-minded Indians at Sand Creek on November 29, 1864. The soldiers murdered children and mutilated the dead. Wynkoop was outraged and damned the victory. His viewpoint didn’t sit well with most whites, especially Denver’s citizens. Wynkoop withstood the harsh backlash and maintained that Sand Creek was more massacre than battle. His behavior before and after the Sand Creek Massacre caused an uproar among citizens of the Colorado Territory and criticism from the press, the military, and the U.S. government. But Wynkoop did not waver. He had done what he thought was right while serving Denver’s citizens, and now he was doing the same with his new friends, the Cheyennes. Despite being condemned as an Indian sympathizer, his name remained on this Denver Street and became the name of Denver’s first craft micro-brewery. The Wynkoop Brewery was started by former Denver Mayor & Colorado Governor, John Hickenlooper, along with his three partners. As with so many of the street names in Denver, pronunciation is all over the place. The sheriff pronounced his name “Wine-koop” but most Denverites these days say “Win-koop”.

As I return home to Osage Street, I notice that my “Rock of Gilbralter”on the corner got tagged – like a dog’s fire hydrant. Nonetheless, I find it to have an interesting graphic appeal and decide to leave the initials up for awhile until I get the time to figure out a strategy for removing them. In a way, a friendly compliment and message to CN from me. I am sure that leaving it up for awhile will not go unnoticed.

After contemplating the rock, I search for my door-key at the end of yet another walk through the hood. As I approach the front door, I notice a curious little creature hanging upside down on my bottom step. This little bat must have lost its way… or not. Red doorways bring good fortune in the “happy home” philosophies of Feng Shui. Perhaps this critter is a good omen, sent from the heavens to rest for the day at the entry to my home. As I gaze at it in another momentary state of wonder, my dogs patiently await as I free them from their leashes to chase each other in circles of joy. Undisturbed, the little bat slept there all day and in the evening, as the sun set, it awoke from its slumber and flew off to join its comrades in the evening Denver skies.

If you liked this blog, please share and get others to subscribe to this website.

Pingback: Stories from the Hood, Part Four – The Flag – John Bonath Fine Art Photography

Mark Sink

Love it …thank you ! … I think you should put this all into a book no? At least a blurb book?

Mark Sink

PS . .. a quick note .. i did not see the credit on the mosaic wall ( maybe i missed it)… it was done by Martha Keating ( government grant)… a great heroic effort that included the whole community making tiles at the Our Lady Guadalupe of Church .. i made many myself.

Peter

As a former professor of Native American Art and Culture I particularly enjoyed your telling the story of the Osage. I have fond memories of Georiana Robertson and her daughter Jan Jacobs coming to talk to my class at CSU. Gorgiana and her sister ran “The Redman’s Store” in Ponca City and were largely responsible for the revieval of traditional Osage ribbon work. I am enjoying your Blog and find the narratives and the images very engaging .

Denver_Mike

Your recounting memories of raising monarch butterflies, having them emerge from their cocoons, and fly around your bedroom was exactly what I experienced at about 9 years old! Sadly, I just read that the monarch population that winters in the forested groves of California are down from 4.5 million in the 1980’s to 29,000 in 2019. Also, I related to your “hunting” with a camera. As you know I do the same with my photography: https://denverphotography.com/africa-safaris. Again, trying for “trophies” of our disappearing wildlife. I found most disturbing the story of the Osage Indians, but again it goes on today. Look at the Rohingya indigenous people, deemed victims by the military of Myanmar of genocide according to the World Court (which was sadly denied by the Nobel Peace Prize winner, Ang San Suu Kyi).

Patty Martin

This post contains such a glorious array of curious flotsam and jetsam left behind. I love the rich variety here.