Eram Qvod es – Once I was what you are now

ARTIST STATEMENT

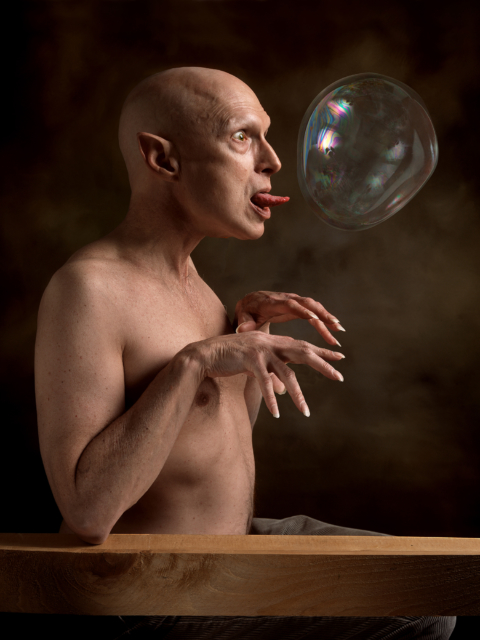

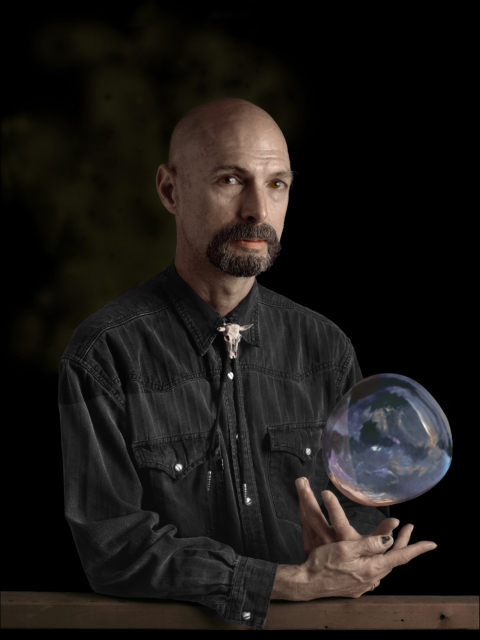

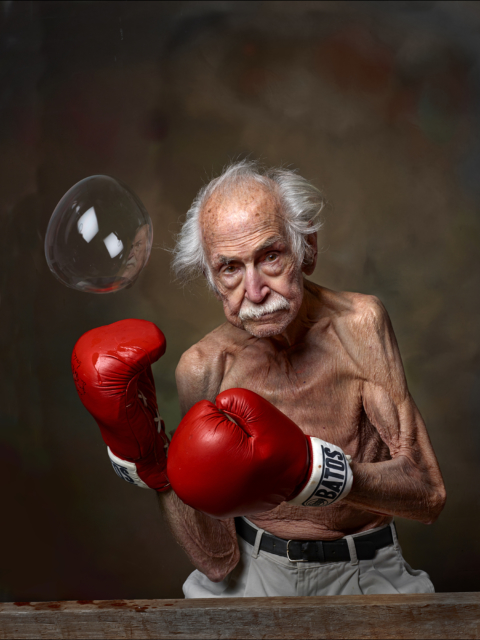

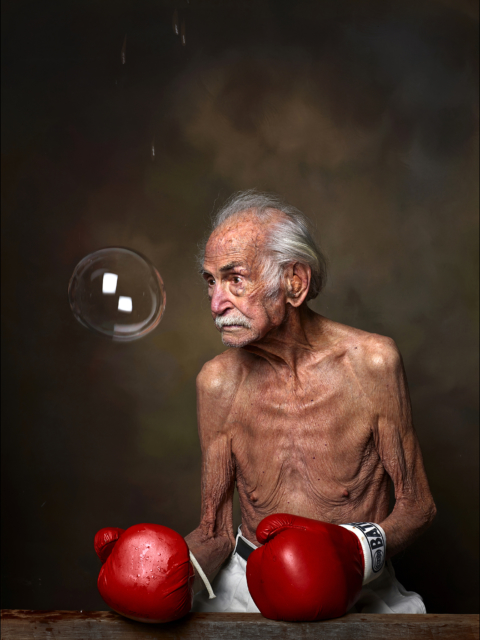

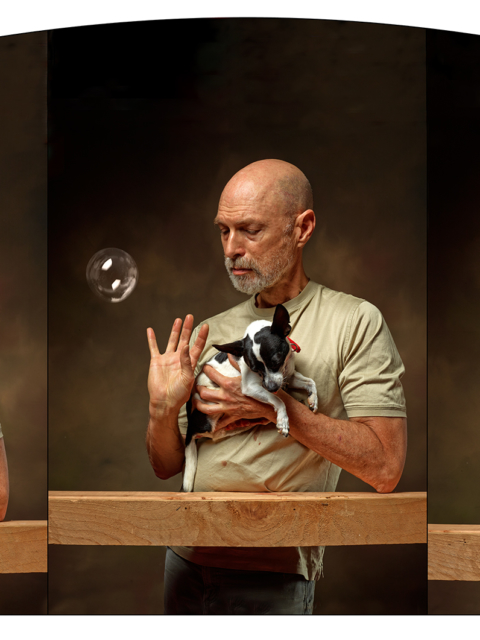

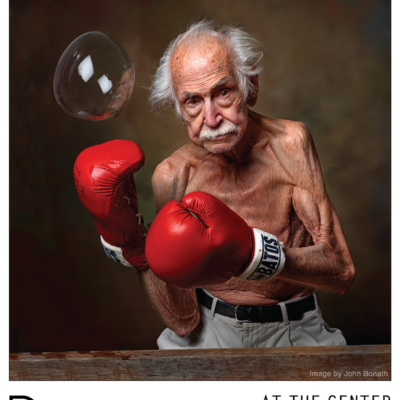

Vanitas (Vanities) is a genre of still-life painting that flourished in the Netherlands in the early 17th century. A vanitas painting contains collections of objects symbolic of the inevitability of death and the transience of earthly existence; it exhorts the viewer to consider our mortality. Common vanitas symbols include skulls (a reminder of the certainty of death); rotten fruit (decay); bubbles (the brevity of life and suddenness of death); smoke, watches, and hourglasses (the brevity of life); and musical instruments (brevity and the ephemeral nature of life). The vanitas imagery of the Renaissance started a rich tradition in art that is as alive today as ever.

The portraits in this series represent epic characters that dwell within our collective psyche. As we relate to them, we ask ourselves questions about these people, our human relationship to them, and in the process, issues of our own mortality.

The bubble is a symbol of each person’s mortality – here one moment… poof, gone the next. As such, it represents one’s life energy, like a self-contained aura. In many of these portraits, you can see the subject’s reflection in the bubble. Most of these bubbles were actually in the original shot. With the way the camera can freeze a fleeting moment in time, the bubble, and the reflections on the bubble, are caught in the static moment of the photograph. To make my bubbles, I use my own formula and construct various size bubble hoops out of pipe cleaners. With practice, I can quickly place a bubble of any size wherever I want it, jump out, and snap the picture.

Installation

Digital Dreaming, John Bonath's Mirror of Imagination, excerpt from an essay by Jan E. Adlmann

Bonath’s “Vanity Portraits” (“Man in Blue, Michael Rolf Ensminger,” “A Taste of Chemo, Self-Portrait,” and “Woman with Black Polka Dots, Marina Graves,” for example) strikingly appear to derive from the artist’s sharp-eyed study of some of the great Netherlandish masters of Renaissance portraiture. Echoing not just the classic poses of such portraiture—usually a profile or three-quarter head an upper torso, often presented as though poised in a window embrasure—Bonath most tellingly also repeats their customary, razor-sharp details and their intense, glittering, vitreous color.

As in the paintings of the great Van Eycks, or Van der Weyden, or even the German master, Albrecht Dürer, the observer feels it may be possible to count every hair on the lady’s venerable head, or in the gentleman’s beard. In the “Chemo” image, where the artist gesticulates like one possessed, the details of the demonic finger-and-ear tips seem to have been whittled to fiendish points.

Adding to the occult, obscure atmosphere of many of Bonath’s “Vanities” are such curious details as the quivering “bubbles” in the images, elements clearly meant as symbolic but, as in much of the art of the forgotten past, this is symbolism lost upon the present-day viewer. That inscrutability, moreover, is the very essence of much “magic realism,” bearing out the famous dictum of Georges Braque that, in art, the only thing that matters is the thing you cannot explain.

Constantly, in the entire body of Bonath’s work, the viewer can only marvel at the uncanny intensity of his color. The satiny jacket of Mr. Ensminger (textured to an amazing degree, due to manipulation after the fact) has the profound depth of the finest Russian lapis lazuli. “Marina” is enveloped in a marvelous, red robe with all the fiery glow of pegion-blood rubies.

“Distinguishing imagination from perception,” as he has put it, Bonath can spend anywhere from minutes to many hours infinitesimally tweaking his color, texture, line, perspective and volume. “Some images are very much like the original shot and only have color correction…but, even in such,” he continues, “I may aesthetically redesign a fold…or other, very subtle things to get the image to…crystallize to the desired end.” The operative word here is “crystallize”; Bonath’s photographs are almost invariably so hard and crystalline we feel they might shatter at the merest touch.

That oddly “mineral” quality in Bonath’s substances and surfaces, a sort of eerily obdurate materiality, not unlike marble or pietra dura, is the aspect of his work which further allies him with still another brilliant, intensely bravura epoch in the history of art, that of Italian Renaissance Mannerism.