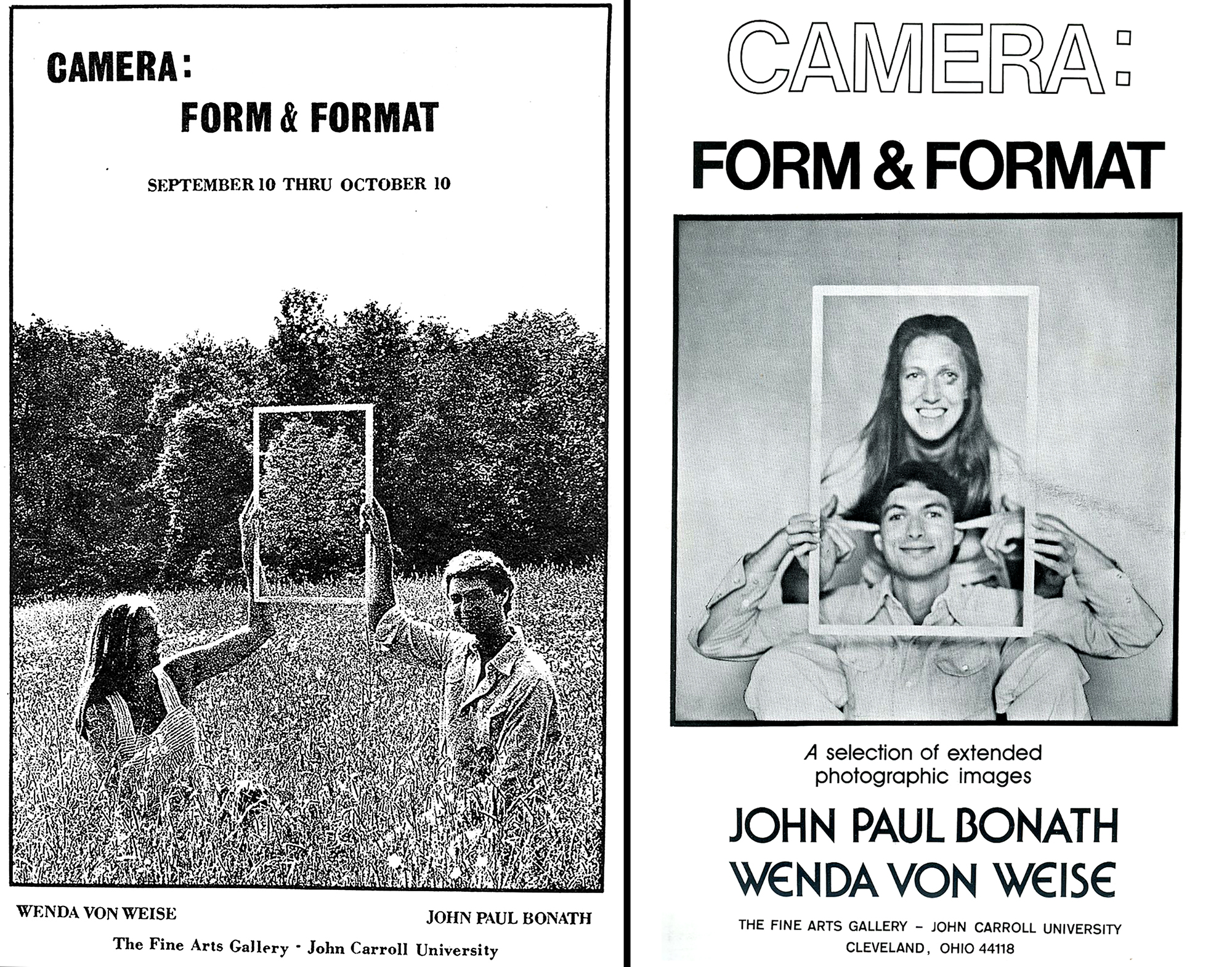

Essay by Robert Getscher from Camera: Form & Format

CAMERA: FORM AND FORMAT

Wenda von Weise | John Bonath

The Fine Art Gallery, John Carroll University

Introduction by Robert Getscher, Director

Photography seems to consist of choosing an object, framing it the viewfinder, and printing the resulting image on paper. At the simplest level we are pleased if we have an image of our favorite dog, and upset if her head is cut off. But the creative photographer is interest in the final print. For John Bonath and Wenda von Weise even the their prints are merely further suggestions for formal manipulations, manipulation first suggest by confronting the object.

Von Weise insists that she and Bonath rarely go out to photography with a specific goal in mind. One can see her ranging over the landscape, camera in hand, eyes darting back and forth, halted by stray interruptions of nature, a feather, in some weeds, a shell on the beach, a discarded piece of wood, which she captures on film.

With Ansel Adams or Minor White, objects have a meaning that is captured and exalted through film. The art of photography is an exacting and even mystical experience. Von Weise‘s photographs are merely stuck in her little black box, kept safe, to be drawn forth and fondled later. She will make a print, or several prints, until she has an image that pleases her. Yet the playing with the developer, the fix, the bath , are just part of the process of turning the image over in her mid, responding to it, running her fingertips over the shell, tickling nose with the feather as ideas form and grow. Perhaps her shadow crept in while photographing, perhaps the light fell a certain way, and a shock of wheat became a bearded lady, or a shop window lead her on.

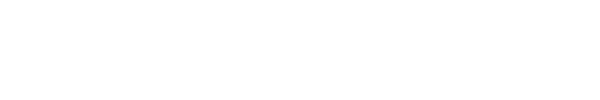

During the creative process an artist like Paul Klee would continue to play with his work until the last stroke of his brush, letting his thoughts be modified by what was happening in front of him. Von Weise starts that way, but at some point she has to stop and calculate, pre-determine what her next step will be. She selectively paints her photographic emulsion on paper, exposing some areas and leaving others blank. This is done carefully, often with systematic variation, to control her image. A discarded square of wood with a circle cut in it is blocked in and out, variations of a circle in a square.

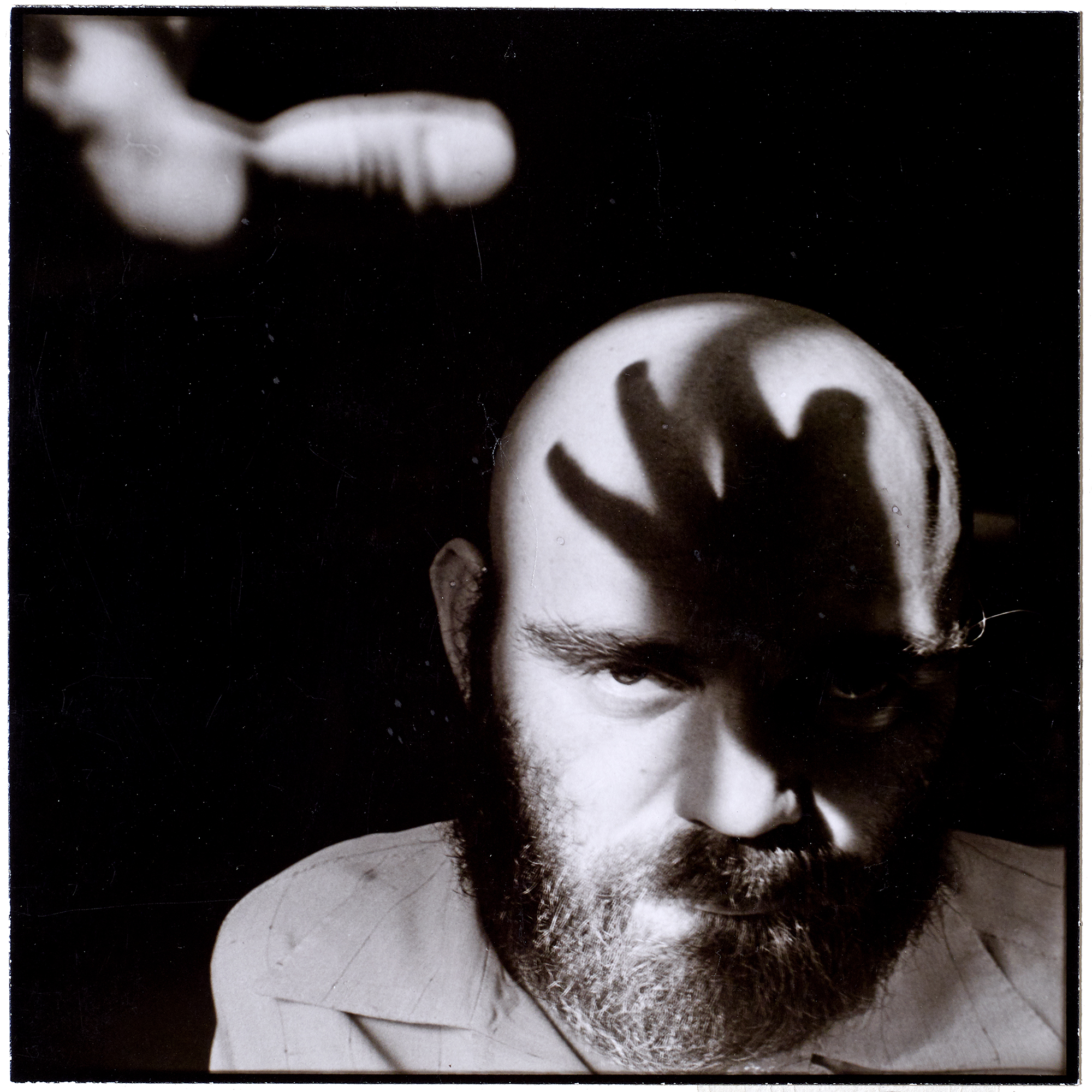

John Bonath is not nearly so free-wheeling in his approach. He searches out forms that have a natural dynamism to them, rocks with slits and cracks, cracks on a sidewalk, or clouds. These are photographed to stress their natural dynamism. In his straight photographs the image can seduce us. In “New Year’s Day” the reflection of the weeds are beautifully atmospheric, like Peter Henry Emerson, a small, delicate, graceful photograph. Or in “Delpha”, blades of grass push through a crust of snow like strokes of Japanese calligraphy. But even his pale images have a firm black edge. This edge determines the relationship of objects within this format, and becomes an impetuous for new relationships.

Often his prints are dissected and rearranged, sometimes violently, sometimes with the precision of a surgeon. Floating clouds are torn out of context, with jagged ripped edges like torn paper. Or a photo is so tipped that recognizable clouds fall into frame-like forms that avoid any sense of gravity. Te recognizable falls into the unrecognizable.

One of Bonath’s most beautiful and complex prints is “Interlock”. Through toning various prints that already seem interlocked, through pasting, but actually through the process of printing, the distinction between bushes and clouds are confused. Shifting planes and colors also work to both fuse and separate the images. This kaleidoscope is carried further by interweaving smaller images of clouds among the larger ones. Te colors are both natural and arbitrary, so that we remain conscious of the artificial nature of its image. This is a rich, joyous prints, evoking springtime with the clouds scudding across the heavens faster than the eye can follow. The use of colors might seem like painting, or color photography. But it is only photography’s sense of anonymous increment, spliced together in richly ordered profusion, that suggests this sense of time more strongly than place.

For Bonath it is important to explore the vocabulary of photography, to stress the rectangularity of the image and yet to manipulate it, bend it, break it so that we become conscious of how we are looking, what we are accepting as true. Something as simple as a dog laying down can be split and reassembled so that it seems relaxed and at ease. We accept the image unthinkingly. Yet if we think about it, none of the whole images are possible, ad all the single images we think we see are composite unreal ones.

Or a tree gets repeated along its trunk, its line of growth , and the branches spill out of the picture plane. Or rocks are repeated with changing colors in frames as if they are rising. In “Projection”, squares of light made by toning stress the relations between squares and grids. In “Docking to the Locked Format”. a section of landscape seen through a tunnel has been cut out. It no longer seems to fit this powerful curved form that has been regularized so that its receding orthogonals line up with the horizontal. Our clues to distance have been twisted to fit the visual frame, making a form too strong to contain nature.

Or the skeleton of a dolphin is repeated like sardines in a can, or like parts of a spinal column. Or silver prints of leaves are wrinkled and pushed and folded, as crumpled as the leaves themselves. Or a photograph of a sky is beat and folded like Origami, pushing out into space, violating again the picture plane.

What both of these photographers have in common is a desire not to accept a photograph as an end, but as a beginning. A photo is not a true record of an object, but an emulsion on paper, subject to the control of the photographer. Drawing implies a sense of order. “I can’t draw a straight line” is a common excuse of the inartistic. But they do not mean that art consists of straight lines, on that an artist applies a sense of order, that at its most exalted, become divine. “Great” photographs are often separated from casual snapshots by the same criterion – a sense of order. But i their manipulations, Bonath and von Weise introduce new kinds of order. They seem to ignore the important “subject” and stress the incidental. But this unconventionality makes us realize that order is made, not found. Nature is chaotic, in flux. And when we find order, let us be aware how fleeting it is, and the conventions we rely on to sense it.

FORMAT STUDY STATEMENT by John Bonath

Prior to concentraiting my work in photography, I worked primarily in painting and drawing. Starting with a blank canvas or paper was quite different than starting with camera in hand. The simple act of “taking a picture” fascinated me on formal levels. What I found so fascinating was the manner in which the 3-dimensional space in front of the camera, was translated into a 2-dimensional photograph on paper.

I believe that man has been deeply and profoundly effected by the photograph and its accompanying vocabulary. The understanding of its relationship to us increases inner as well as outer awareness. My search for this understanding is based in the relationships that the elements of my images have with each other and with the space that they occupy.

In breaking down this 2-dimensional representation of space, the first element I formally explored in my thinking was the format. The unique concepts of isolation, which photography has inherent within its frame, have importance in shaping content. In fact, the subject of a photo does not exist before the shutter is released. This makes defining the subject the essential task of a photographer. This is done by organizing the formal elements within the frame to make a coherent visual statement. The format and the image cannot be separated. The viewfinder of a camera is like a window-frame that crops out a section of the space in front of the camera. This frame is an editing device. It is the first decsion-making step in the process of making a visual statement. For example, if there was a body next to a flower; the resulting photograph could be about a pretty flower; it could be about a bloody body; or it could be about the relationship between the two. The structure you create to make either of these statements becomes the composition.

I believe the reality within a photograph is contained within the frame and what is outside of the frame to not be a part of the statement. This idea is especially critical in establishing the design of shapes with framing and the resulting negative and positive space of the composition.

Shapes are cut out as much by the frame as they would be with a cookie cutter. Any visual element that has been cut by the frame, has an edge that is part of the frame. It is the nature of being a 2-dimensional object; much like a jig-saw puzzle is made of many 2-dimensional pieces, the first to be organized are the ones with a straight edge that create the border; when all the pieces become a single image, the illusion is complete. The negative and positive shapes fit together to form the composition. This is the foundation structure on which an image statement is built.

Once the composition establishes the visual elements, it is the relationship of visual elements that create visual content. We relate visual elements together through the Gestalt laws of perception. These various Gestalt laws include premises like Similarity (the more similar two things are, the more we tend to relate them), Proximity (the closer two elements are, the more we tend to relate them), Continuity (lines that are close enough in proximity will tend to be seen as continuous) and the idea of Closure (we want to understand vs. not understanding and will strive to do so).

In my work I am constantly dealing with ordered visual symbols. I consider the understanding of visual tools and vocabulary to be the most important concerns of photography today in stressing an images’ natural dynamism (which may e incidental), I rely on an order that is made, not found. The conventions of visual language are used to make sense out of the chaotic. The defining edges i my work may determine the relationship of objects within this format, or become an impetus for new relationships. My work has tendency to stress the rectangularity of the image and yet manipulate it, bend it, break it so we may become conscious of how we are looking and wheat we are accepting at true. This criterion of order is involve d with aspects o time more strongly than place. By my manipulations, I am able to introduce new kinds of order in hopes of giving the realization that order cones from within and is not just found.

As Robert Getscher has written about my work: “Nature is chaotic in flux. And when we find order, let us be aware how fleeting it is, and the conventions we rely on to sense it.”