On Humor – Part Two

by

John Bonath

Humor in Art

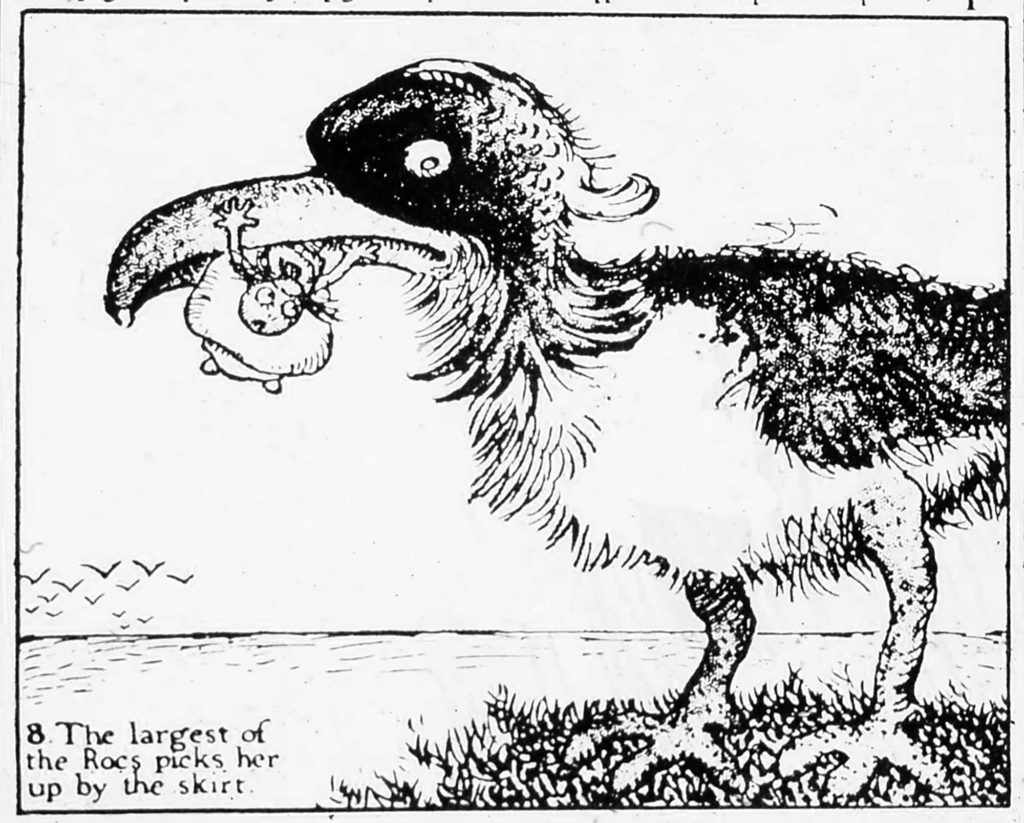

Humorous art can be a dangerous endeavor as traditionally we seem to have the idea that “art” is supposed to be a serious matter. When humor works, it often rides a precarious line between the sublime, the silly, the absurd and the offensive; then again may not be found to be funny at all. But alas, humor and art are both basic to human nature and humor is easily found throughout art history and the contemporary art scene. Aside from individual artists, art movements that incorporate humor have had a major influence on the art we see today.

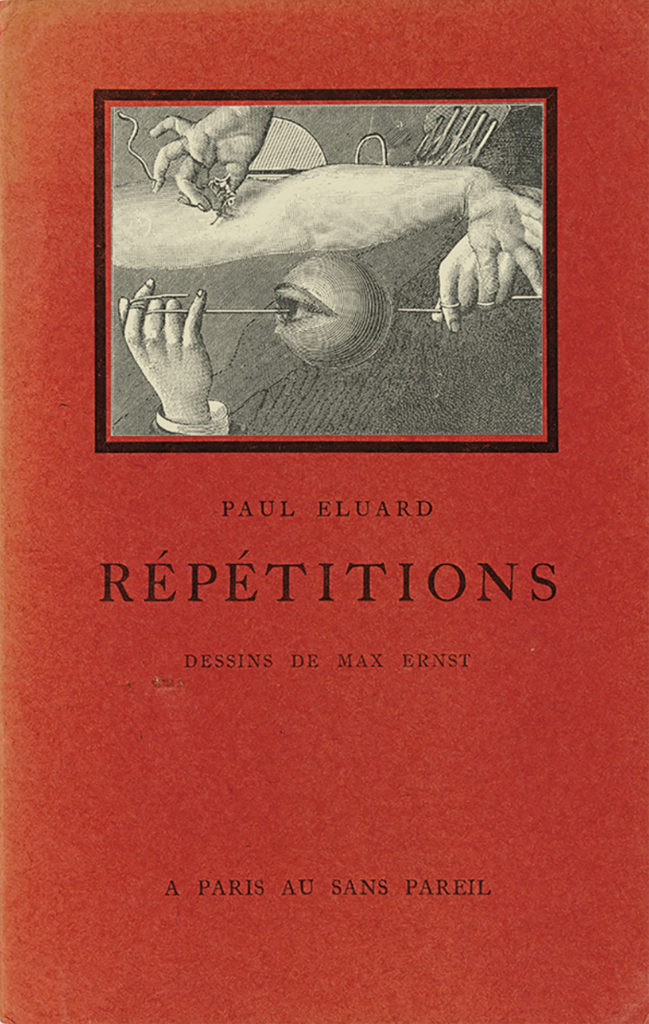

One such art movement that has greatly influenced my sensibilities is the Dada movement of the early 1920’s. Dada artists incorporated humor as a doorway to grapple with difficult topics. While seemingly flippant on the surface, this art movement was fueled by disillusion and moral outrage at the carnage wrought by WWI. Dada is often characterized by clever wit, irrationality, satire, enigma, anti-bourgeois sentiment, irreverence, mockery, absurdity, unpredictability, nonsense, anarchism, revolution, and a questioning of everything that is taken for granted. The made-up word “Dada” itself is nonsense. Dada broke from tradition to create new thinking about art by experimenting with the laws of chance and the “found object” (called “ready-made” art). In so doing, the definition of art was challenged as never before. It turned out to be one of the most influential movements in modern art, fueling Surrealism and giving fertile ground to Conceptual and Pop art. At times when the world seems to make no sense, the impact of Dada art resurfaces and is as alive today as ever, thriving in fertile ground.

“Dada artists incorporated humor as a doorway to grapple with difficult topics.”

A performance by Hugo Ball reciting the sound poem “Karawame” at Cabaret Voltaire in 1916, in which he recited nonsensical syllables in patterns to create rhythm and emotion. He was referencing the inability of European powers to resolve their diplomatic problems through civilized and rational discussion, a dilemma that led to WWI – equating the political situation of that time to the story of the Tower of Babel. It is certainly an easy connection to find meaning in this performance over a century later, recently with an encore performance by Putin and Antonio Guterres at opposite ends of a twenty-foot table.

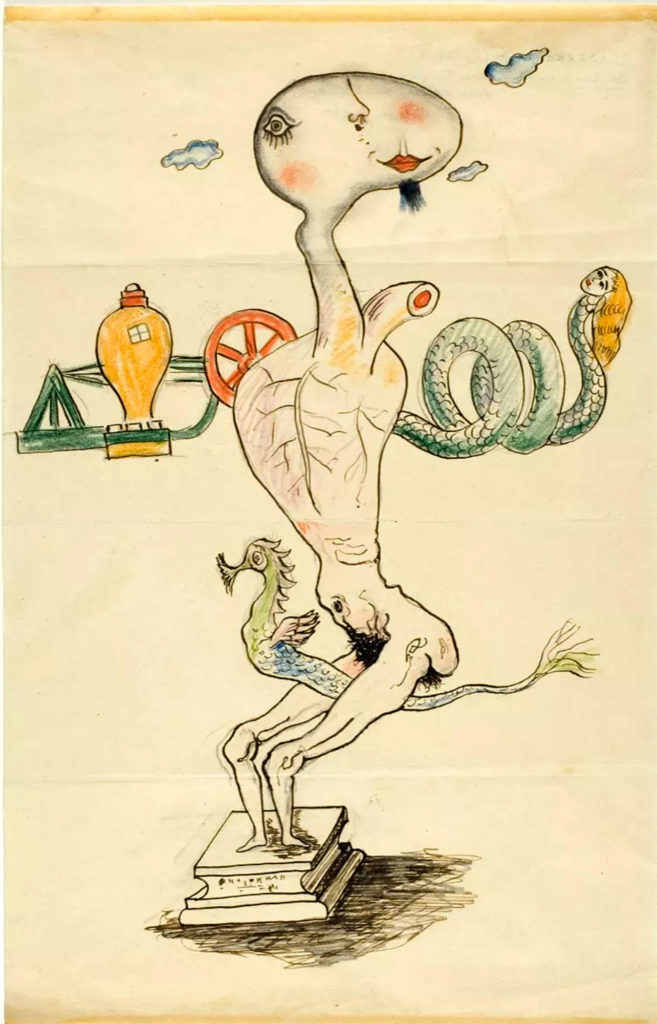

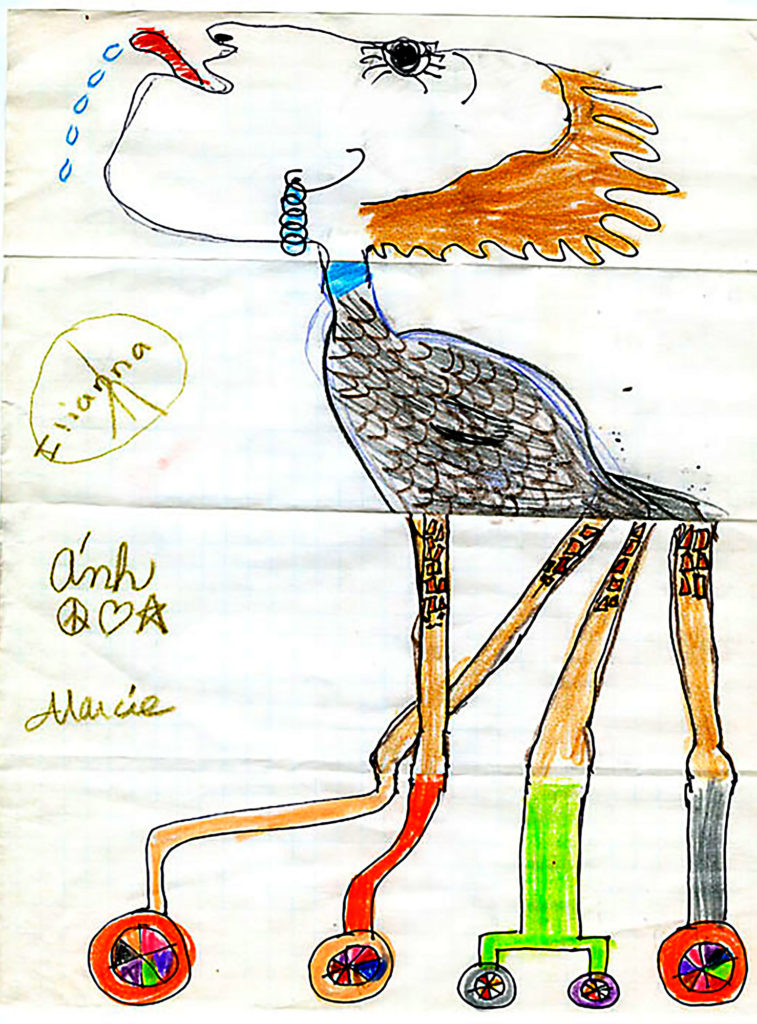

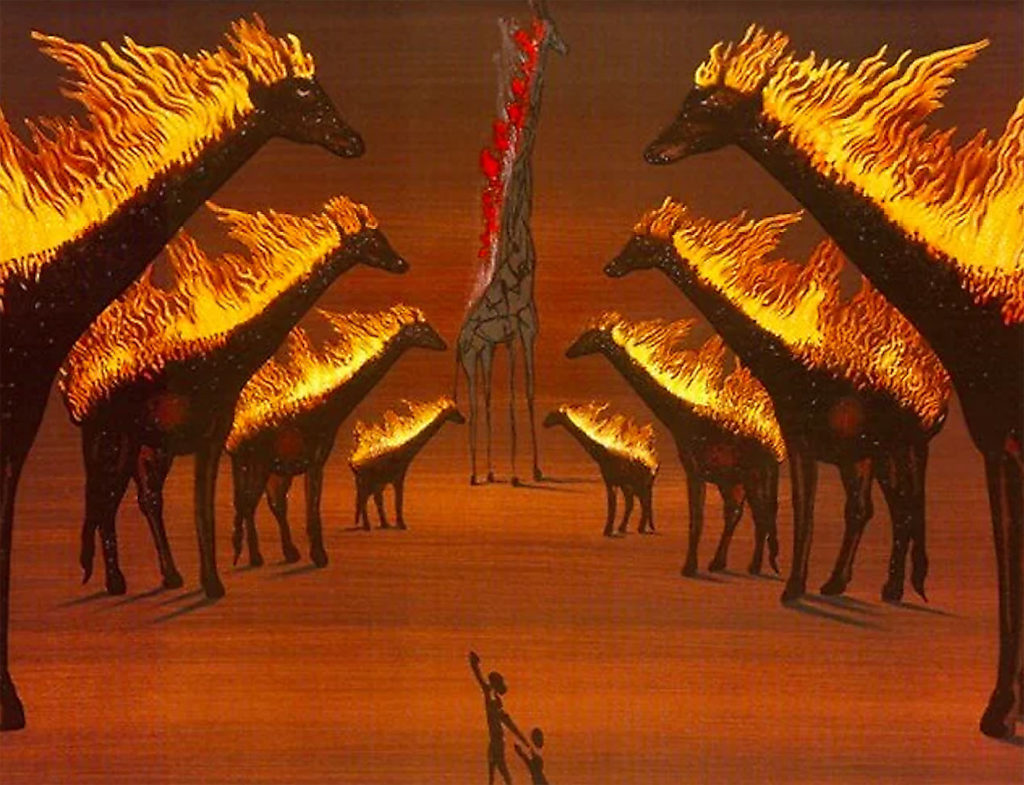

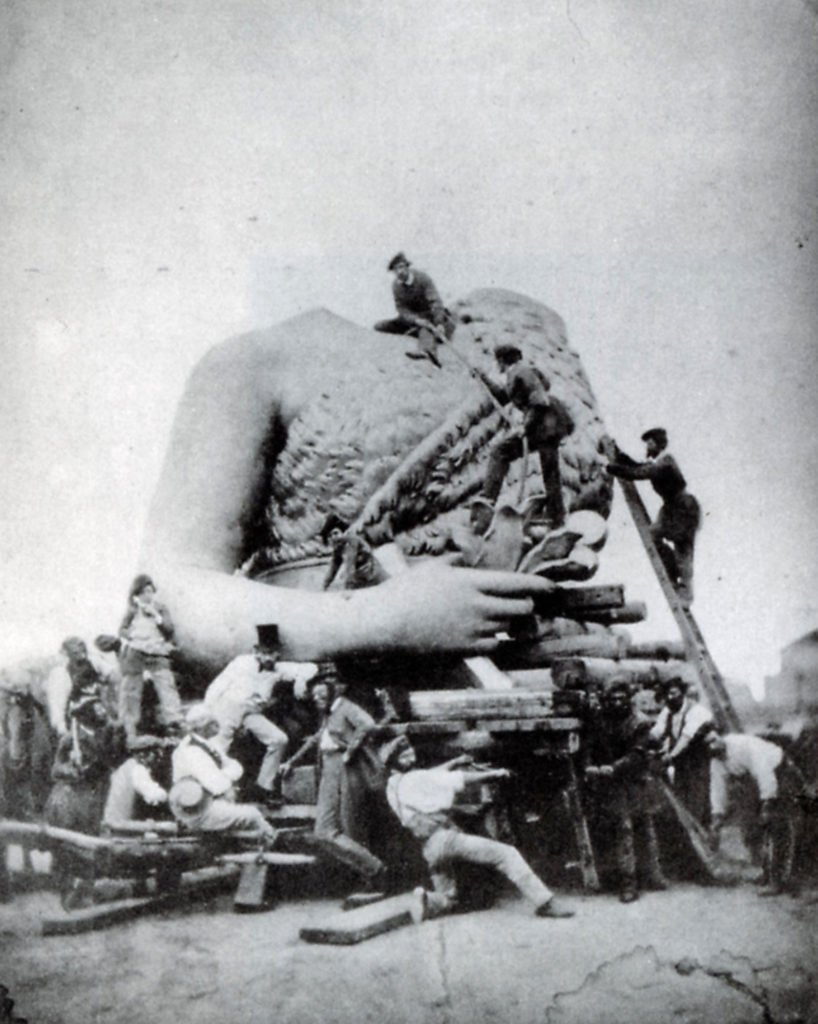

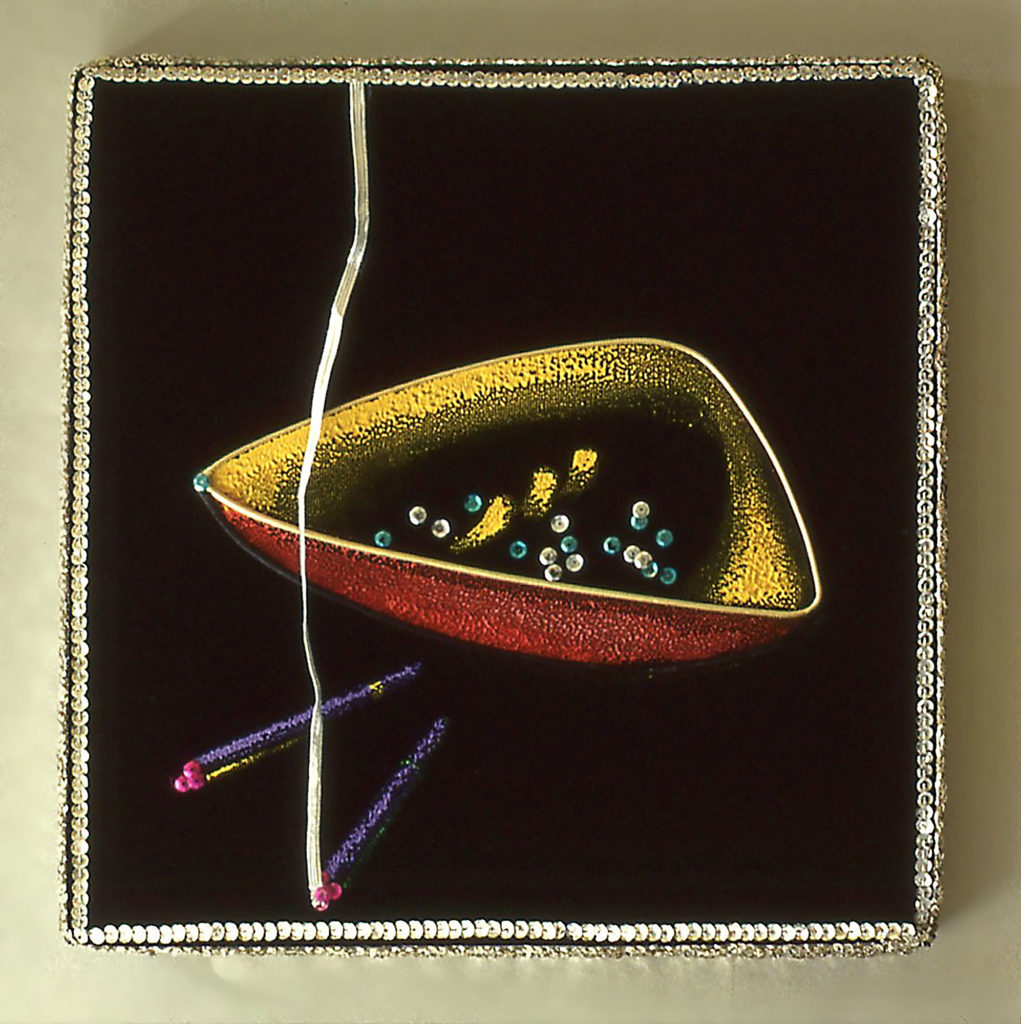

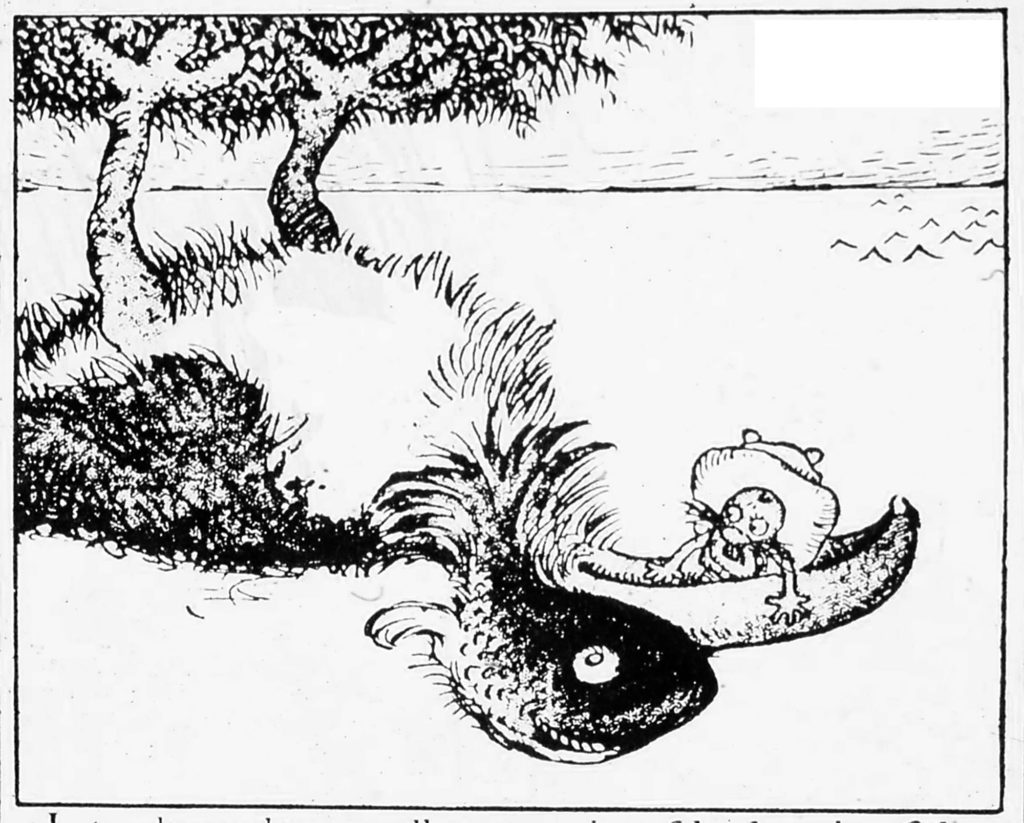

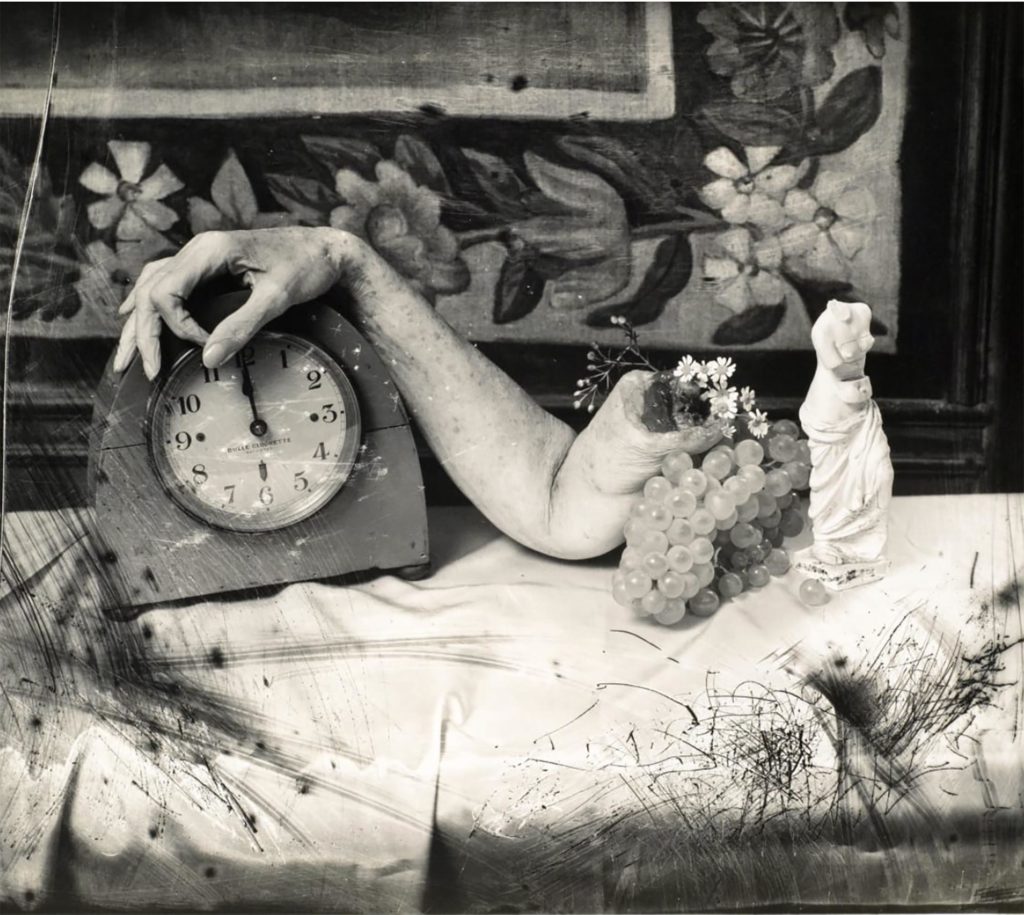

A few representative examples of art from the Dada movement. When looking at these images, try to understand a flavor of humor somewhere in the image experience. What is playful, amusing or humorous in some manner? In much of Dada art, there is a dry wit of absurdity. Sometimes humor is obvious in art, at other times it can be very subtle and even hidden on a personal level.

“The Exquisite Corpse” is a classic game of humor that the Surrealists came up with in the early 1920’s and is still played today. In this game of chance, one artist makes a part of a drawing, folds the paper so only the edges of their drawing can be seen, then passes the folded paper on to another artist who uses the ending edges of the previous drawing as the beginning lines of a new drawing. When the “chance” drawing is unfolded, the result is a fun surprise.

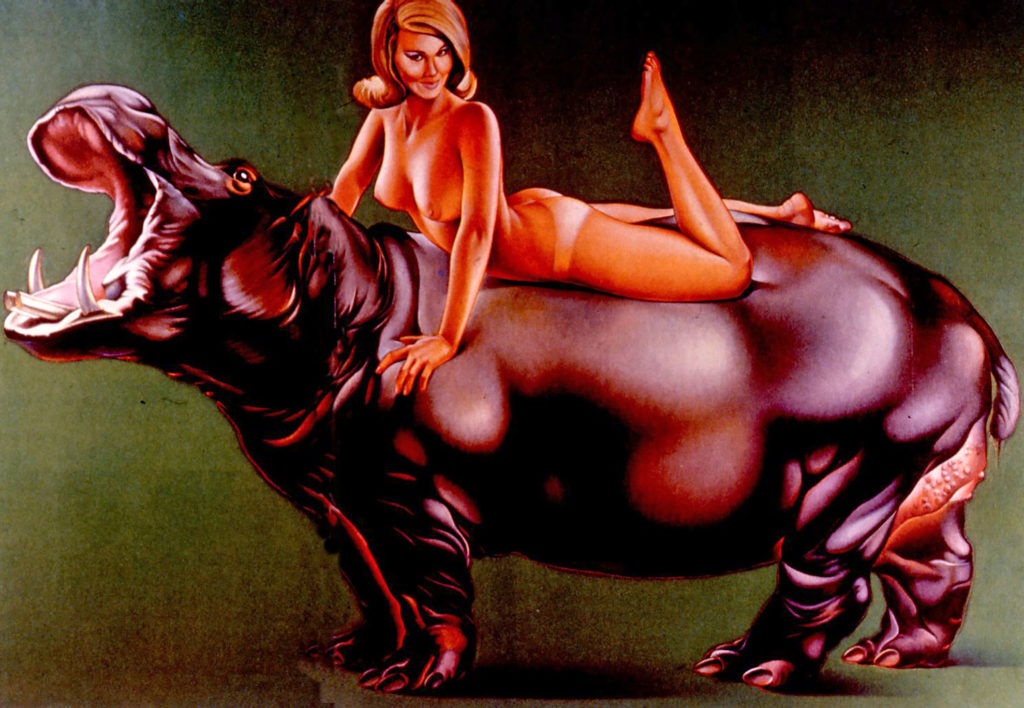

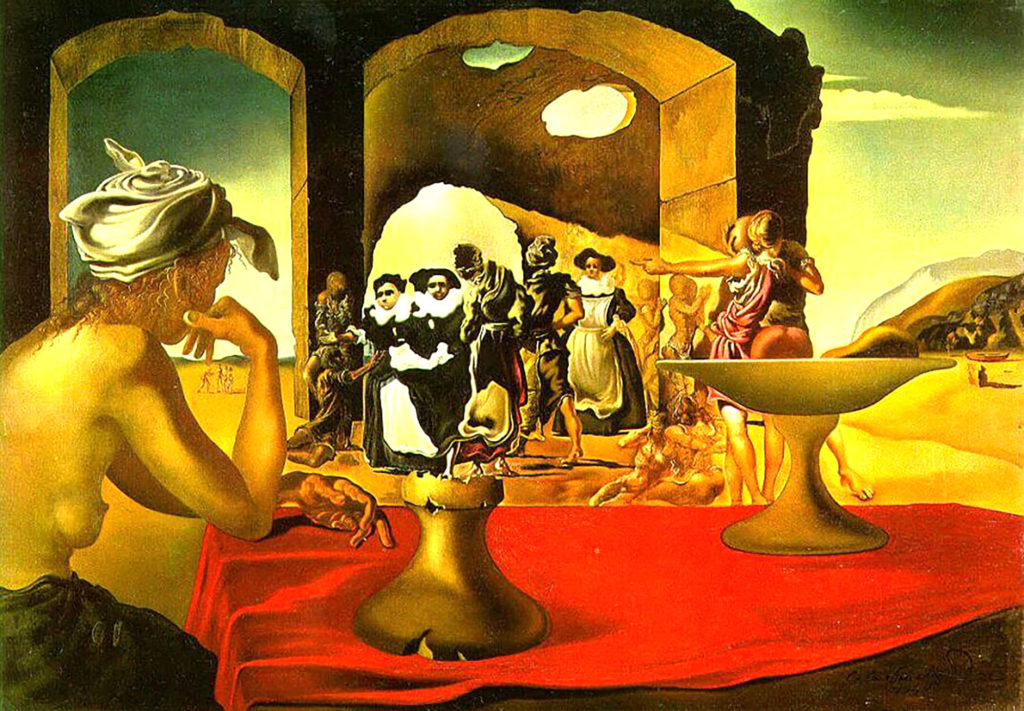

Surrealism grew out of the Dada movement with its own flavor of humor. The brand of humor in Surrealism is a form of humor based on deliberate violations of causal reasoning, thus producing seemingly illogical events. Surreal humor tends to involve a bizarre incongruity resulting in irrational or dream-like situations. Although there is much cross-over between Dada and Surrealism, I tend to think of the humor in Surrealism as similar to Dada humor in its absurdity and illogical relations, but with a less harsh edge, being more romantic and appearing to make sense as in a subconscious dream-like state. Surrealism also differs from Dada in that it doesn’t rely as much on the found or ready-made object.

Sandy Skoglund is presently exhibiting in Denver at Rule Gallery in a show entitled Outtakes, June 10 – July 23, 2022. 808 Santa Fe Drive,, Denver, CO, Tues – Fri 12-6p / Sat 12-5p, info@rulegallery.com, 303-800-6776. Skoglund also presently is exhibiting work in Modern Women, Modern Vision, Works from the Bank of America Collection at The Denver Art Museum in the photography gallery , through August 28, 2022.

The way we percieve anything is effected by what we know or beleive. The same art is perceived differently at different points in history. Today we see art of the past as nobody hs perceived it before.

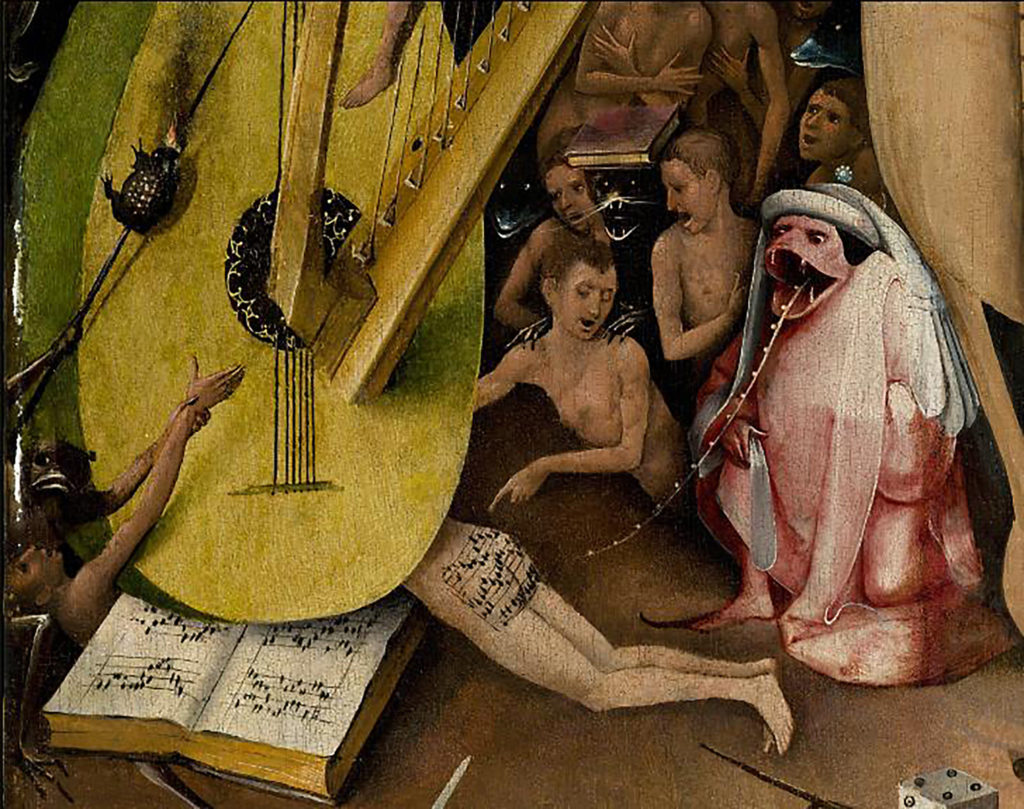

The following are some details from a triptych that Hieronymous Bosch painted around 1500 called The Garden of Earthly Delights. In the left panel depicting Hell, Bosch illustrated the consequence of earthly sin in a way that was supposed to be one’s worst nightmare of what literally happens to sinful souls after they die. The painting is loaded with symbolic language that is a hoot to speculate on. This painting preceded the Surrealist Movement by over four centuries yet is the embodiment of Surrealism. Today this painting is a cult classic and these days is usually viewed from the contemporary perspective of dark humor. Here are a few choice details from this mega-dense religious work of art. It was not meant to be funny, but to the modern mind, these images of what hell is like are quite hilarious to consider.

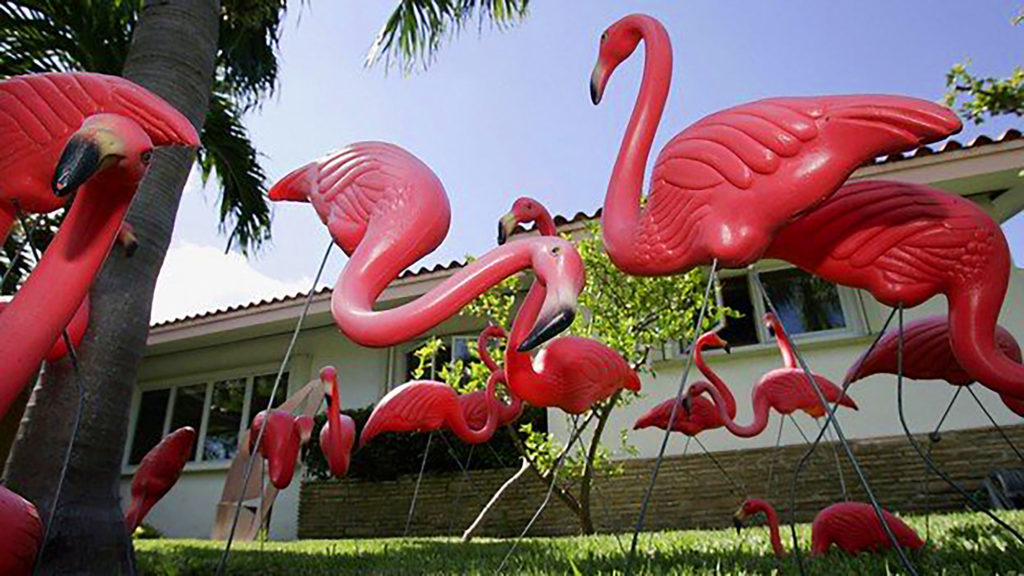

I can’t talk about humor in art without dedicating a special category to an appreciation of the Kitsch. Kitsch is its own special art genre that people relish for its absurd cheesiness or garish tack, this factor is what constitutes its charm and humor. For someone who “gets” Kitsch, it will evoke a laugh accompanied by a big smile; for others, their sophisticated “taste” will be offended; and yet others might find it seriously beautiful with the “Kitsch-factor” going right over their heads. Kitsch can be naive art or a respected form of fine art. Oxford dictionary defines Kitsch as “art, objects or design considered to be in poor taste because of excessive garishness or sentimentality, but sometimes appreciated in an ironic or knowing way”. The cultural critic Walter Benjamin, defined Kitsch as “something which offers instantaneous emotional gratification without intellectual effort.” According to many experts, Kitsch art cannot be considered as “art” at all, or it can, but it would be “bad” art. Good Kitsch, (or do I mean bad?), is quite alive in some of today’s best contemporary art. I just came across a call-for-entry from ShockBoxx Gallery in Florida, which calls itself a “cutting edge” gallery. They are having a show later this year called “Here Kitschy Kitschy”. In their entry prospectus they say “Just make sure it’s bad, really bad…” and are looking to feature “the best working artists”. Interest in this show attests to the ongoing popularity of Kitsch.

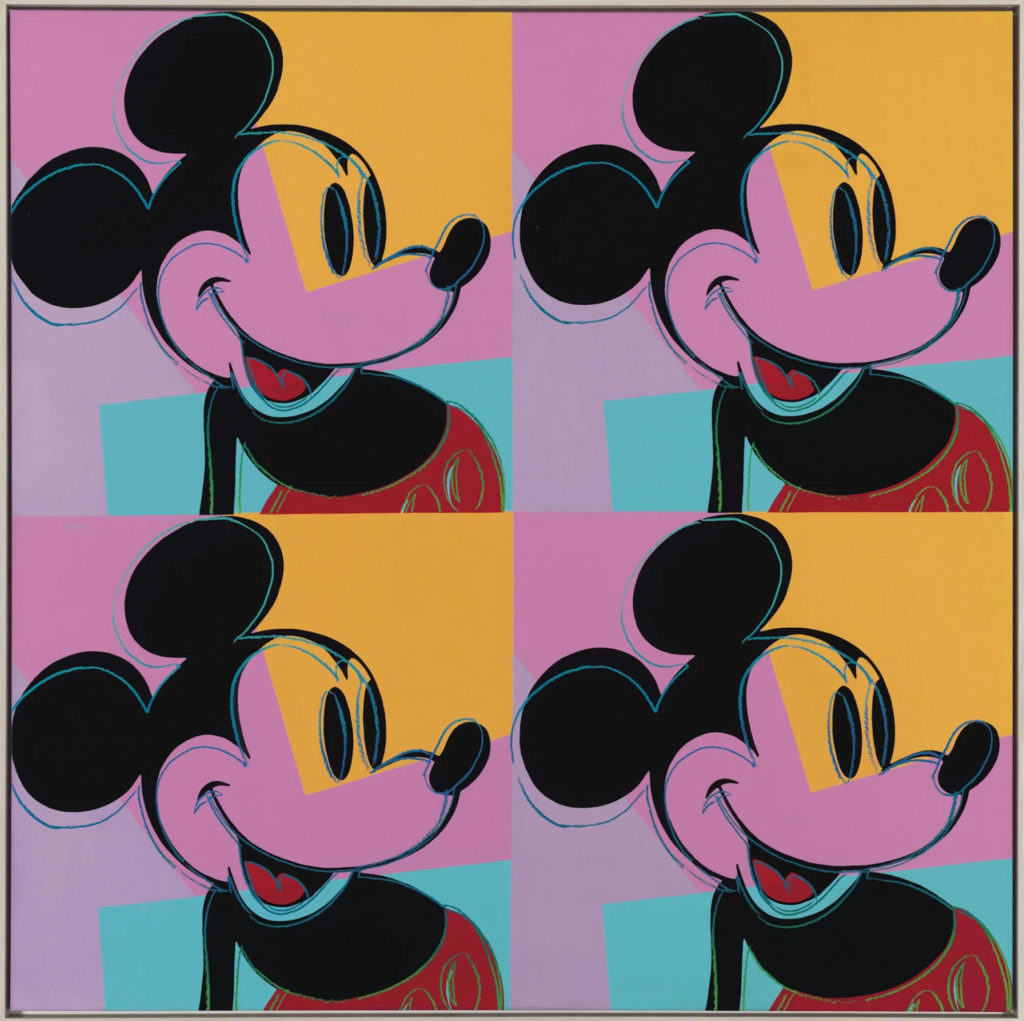

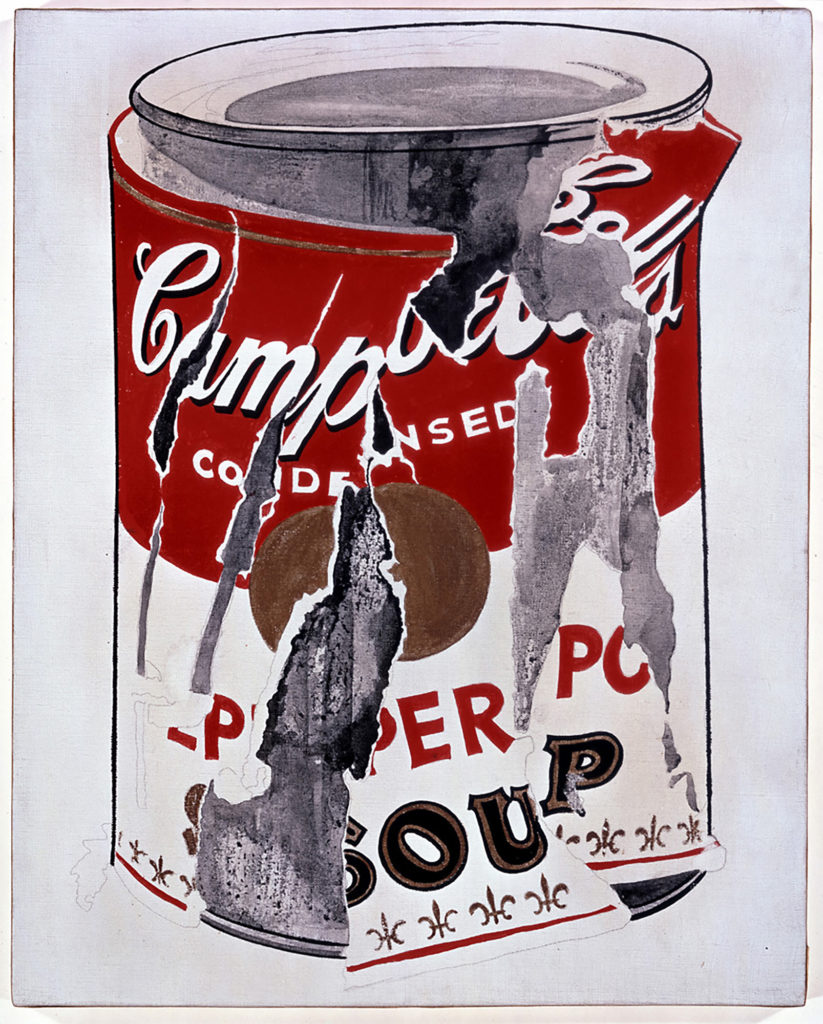

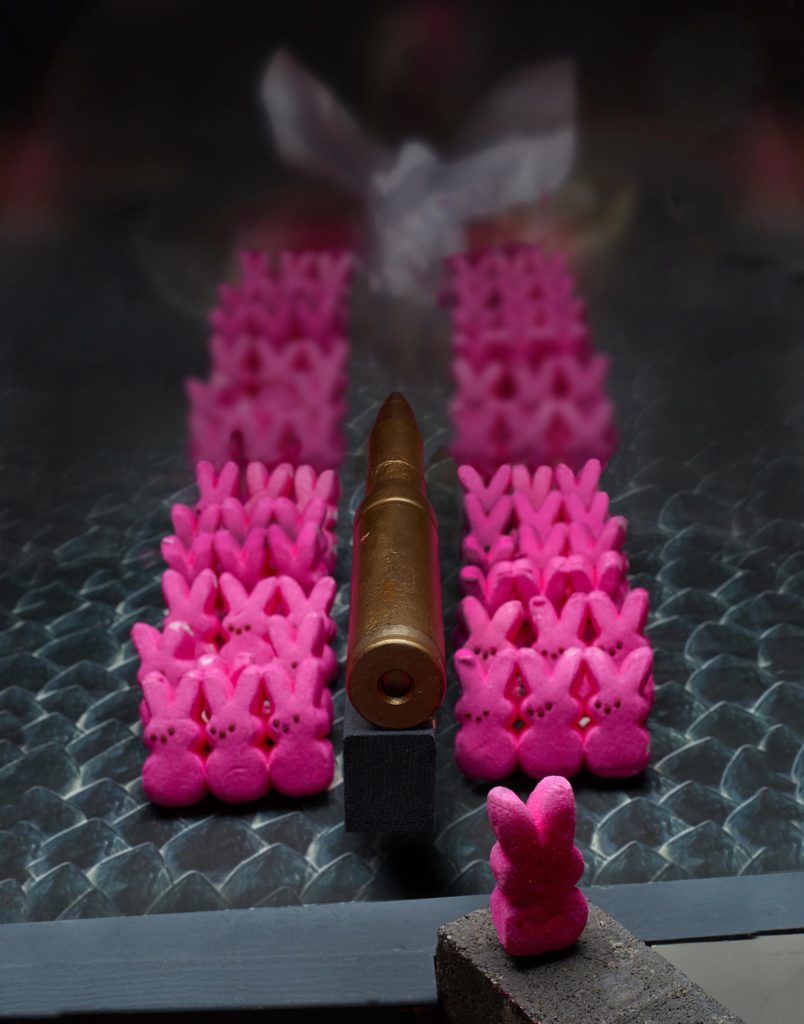

Many top contemporary artists are accused of implementing Kitsch elements into their work, such as Jeff Koons, Andy Warhol and Yayoi Kusama to name just a few. These artists purposely use Kitsch with abandoned intent because they like it and it emotes a response. Although these amazing artists are accused of making “Kitschy art”, they are among the most successfully recognized contemporary artists around. Without getting into existential hypotheses about “What is art?”, there are many different views on Kitsch art. Oxford Art Dictionary suggests that “Kitsch art” is “Art”, as simple as that. Art is ultimately a subjective experience and what is for one person the horror of Kitsch, is for others a spicy and wonderful experience. Tapping into the Kitsch, with a detached air of objectivity, can be a very sophisticated genre of art replete with wit and humor. There are many objects in our culture that have become icons for just this reason. One such Kitschy icon, the pink fluorescent bunny Peep that seasonally lines store shelves, was the motivation for this blog.

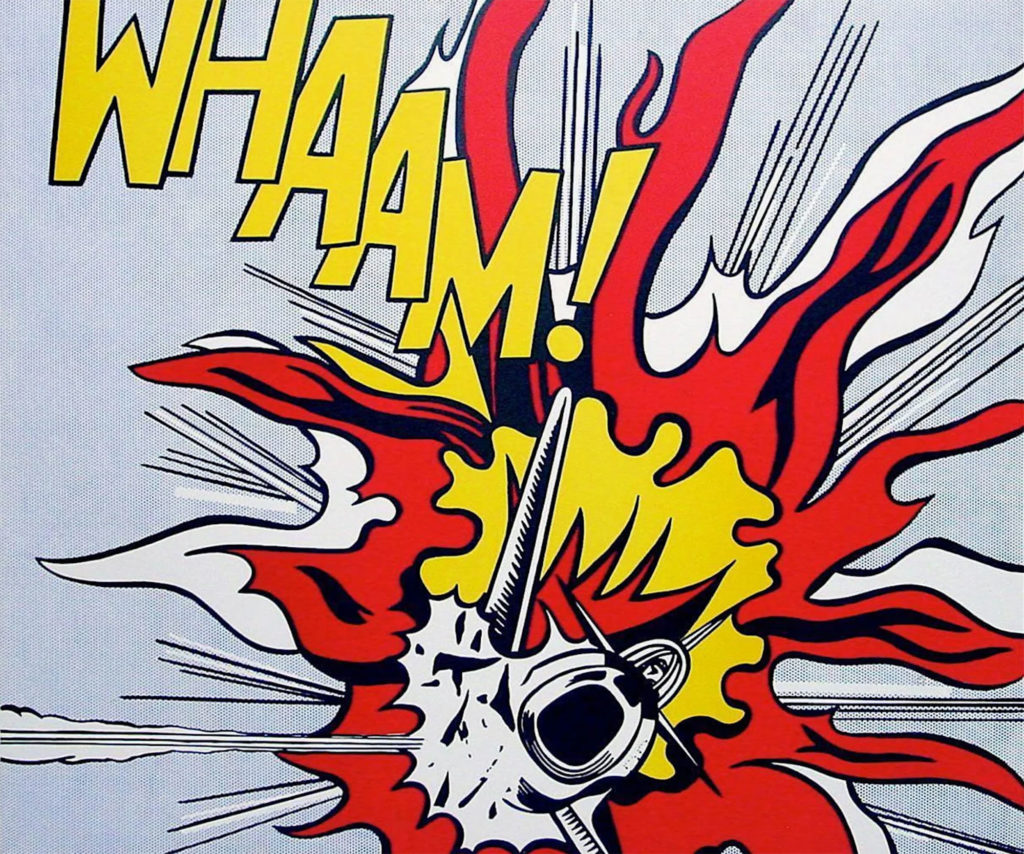

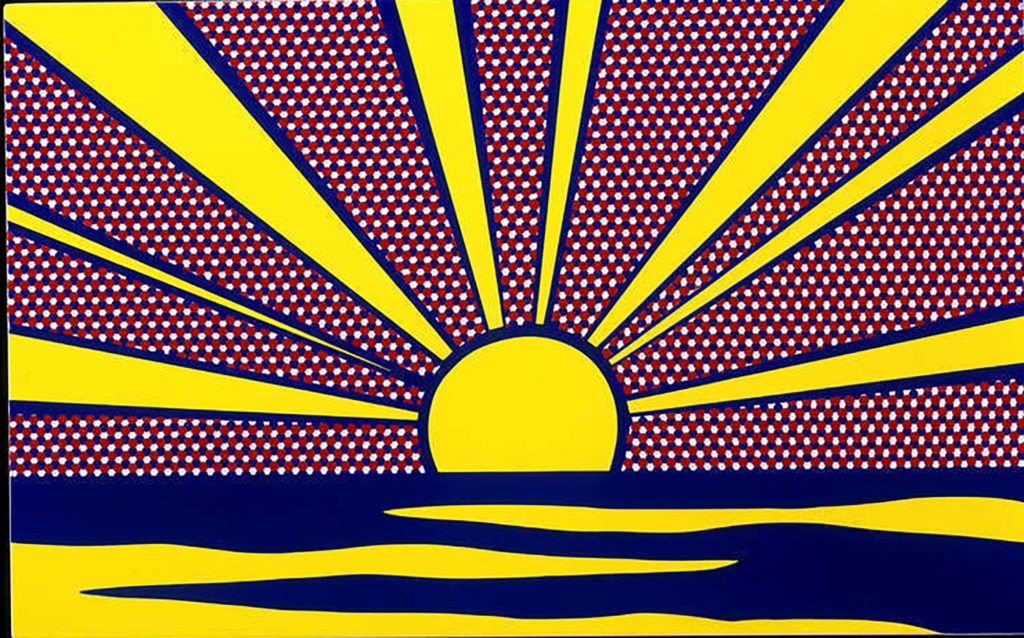

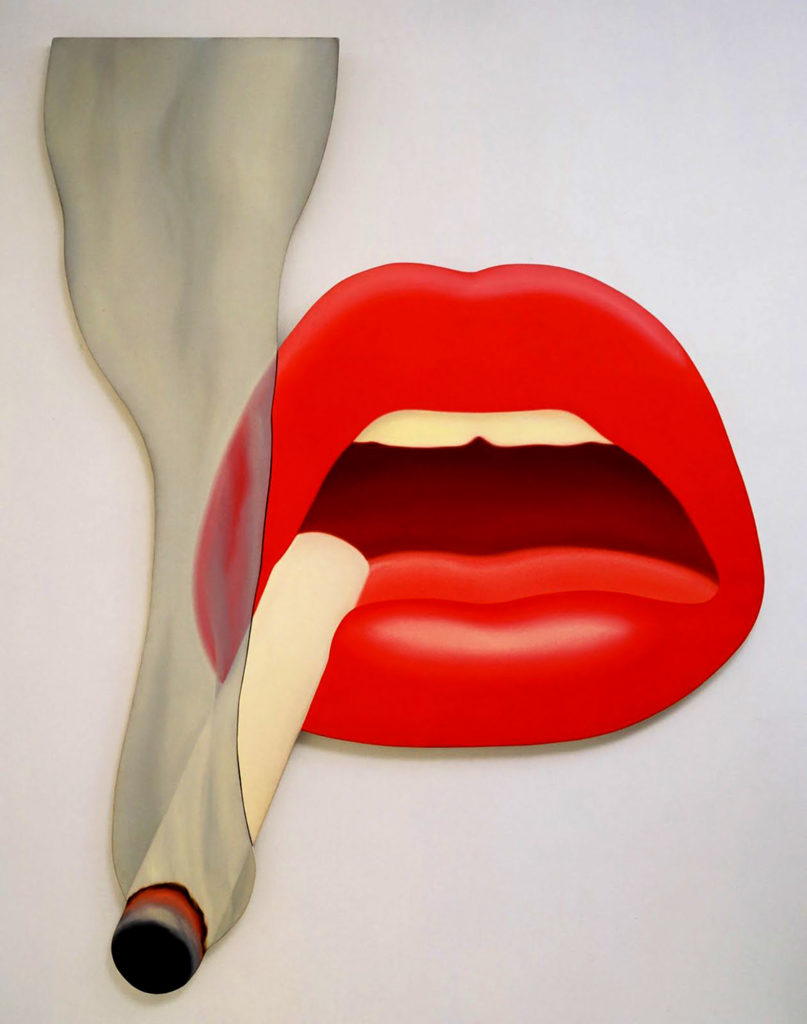

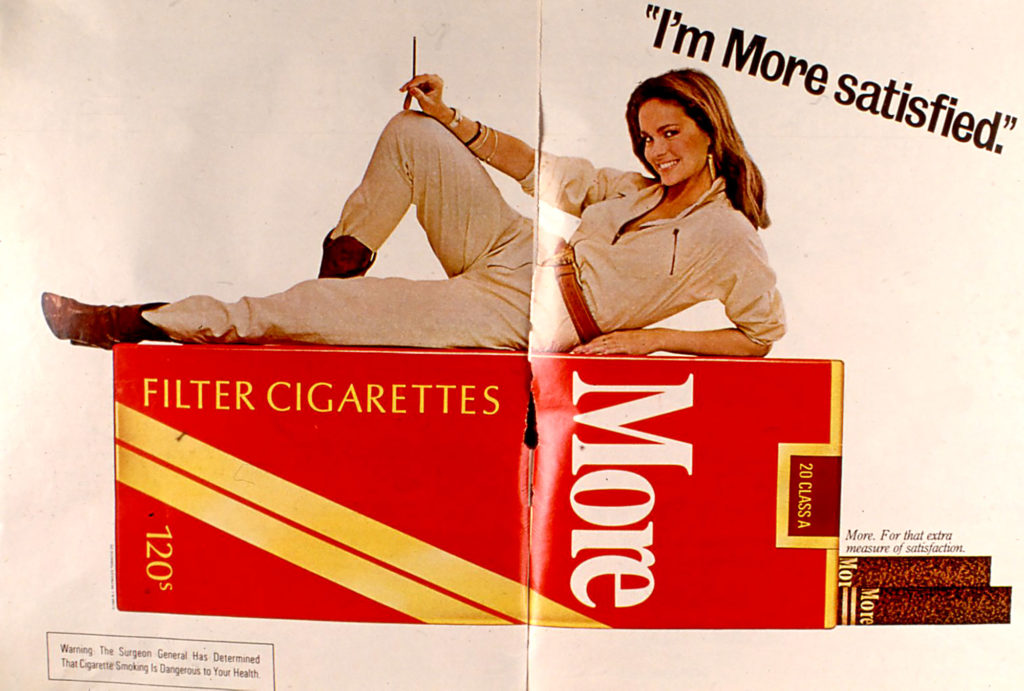

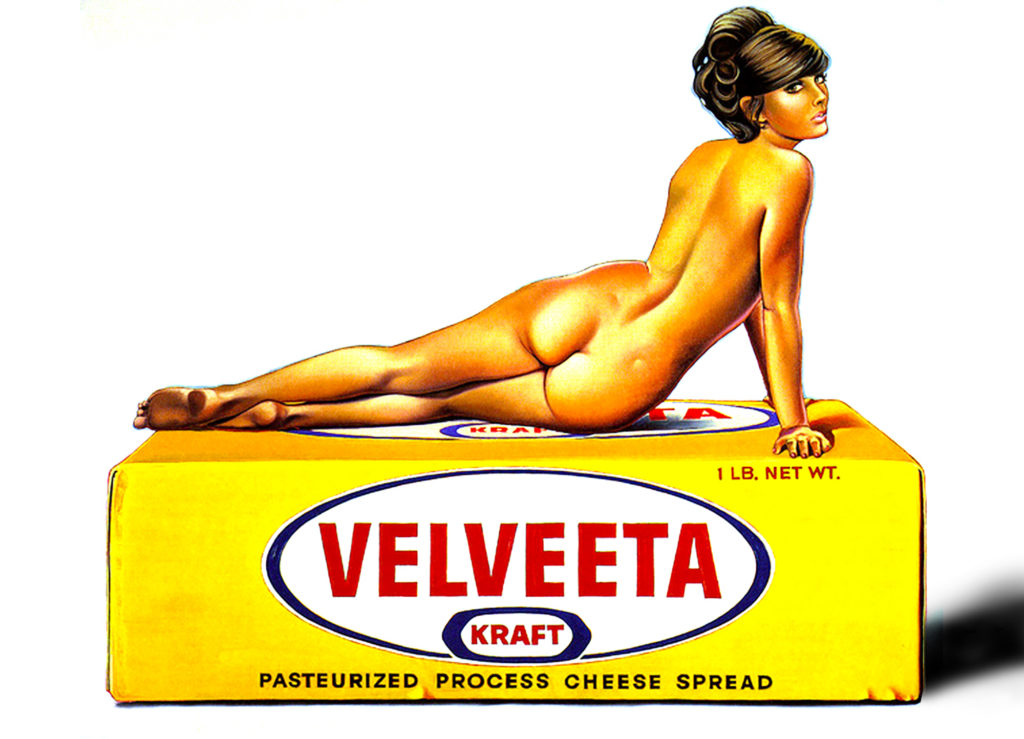

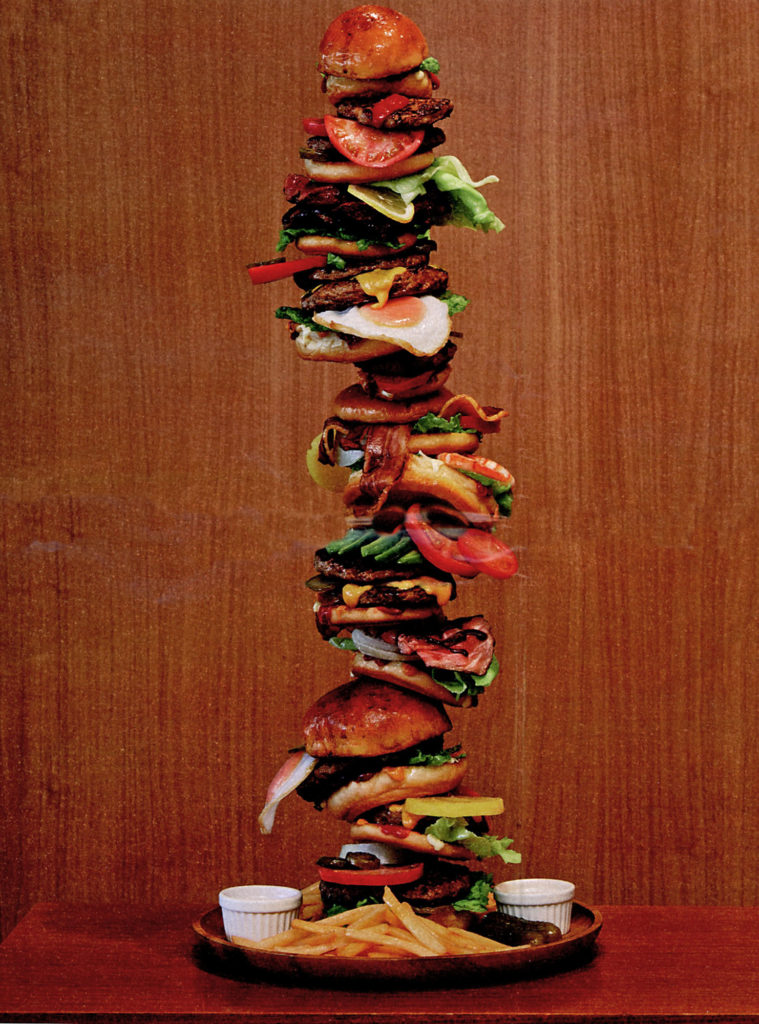

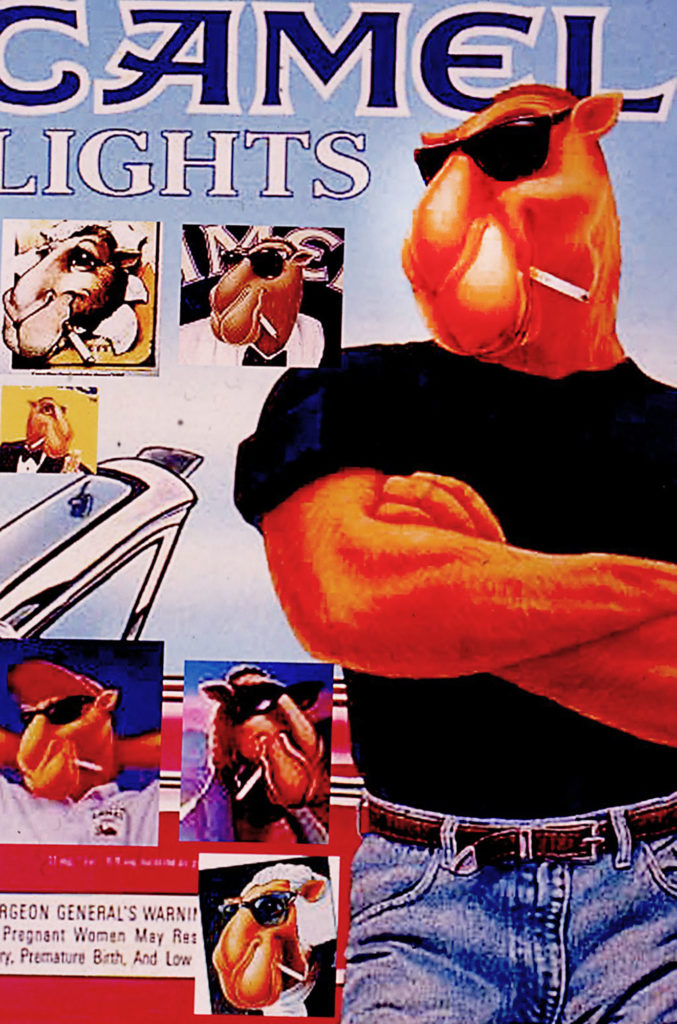

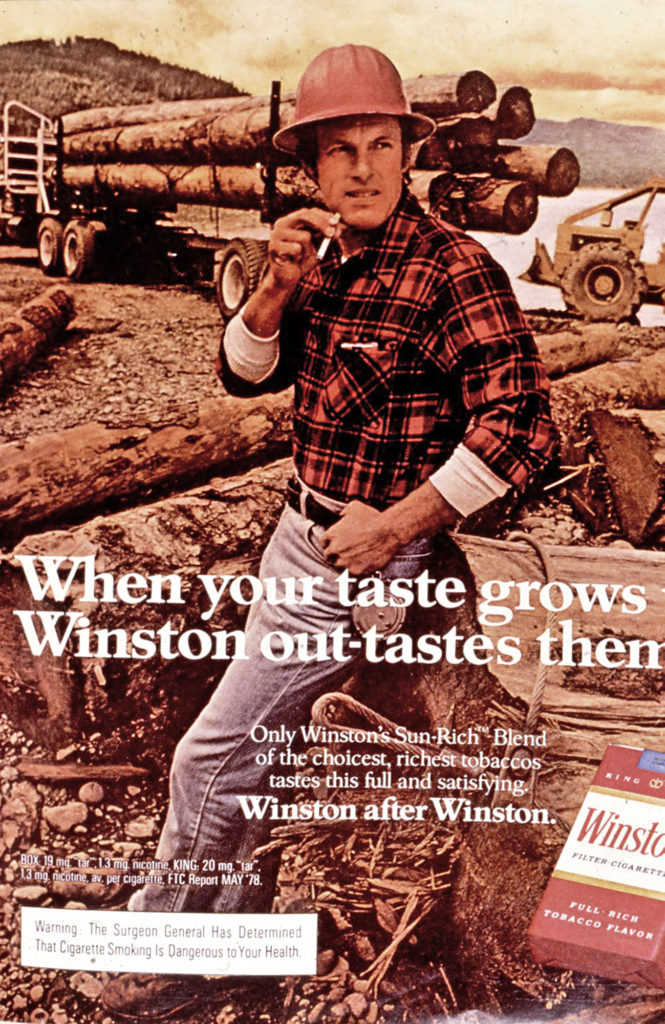

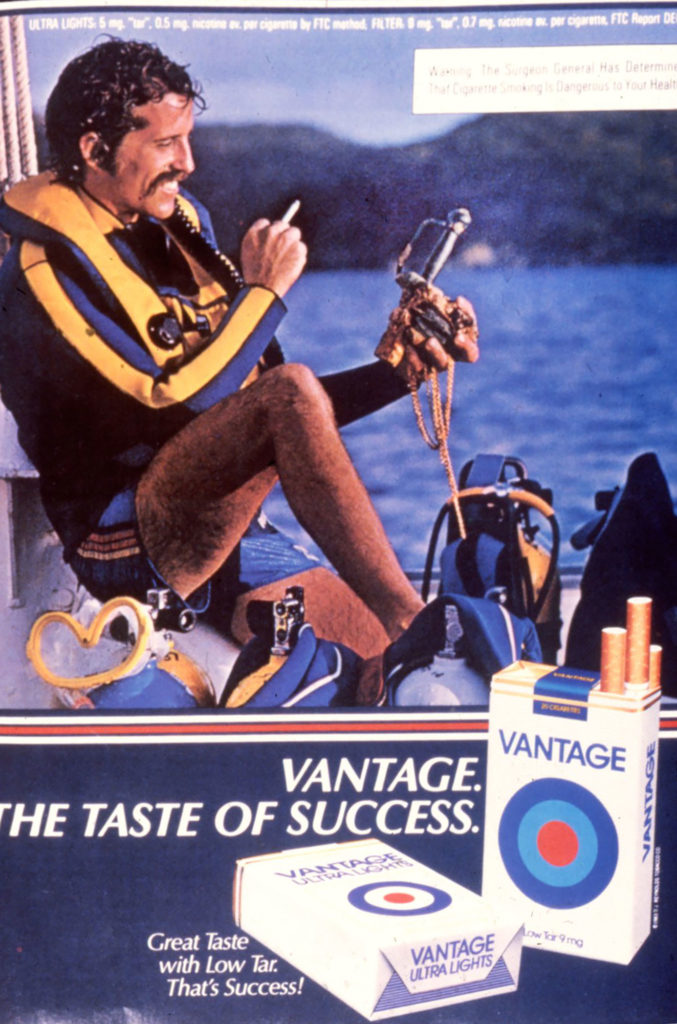

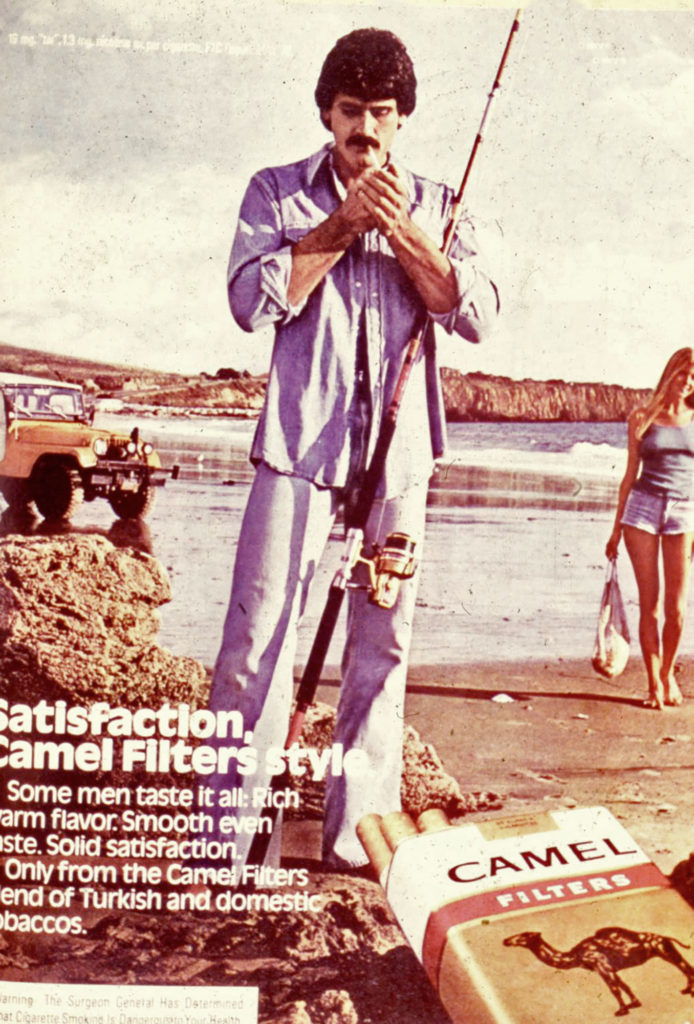

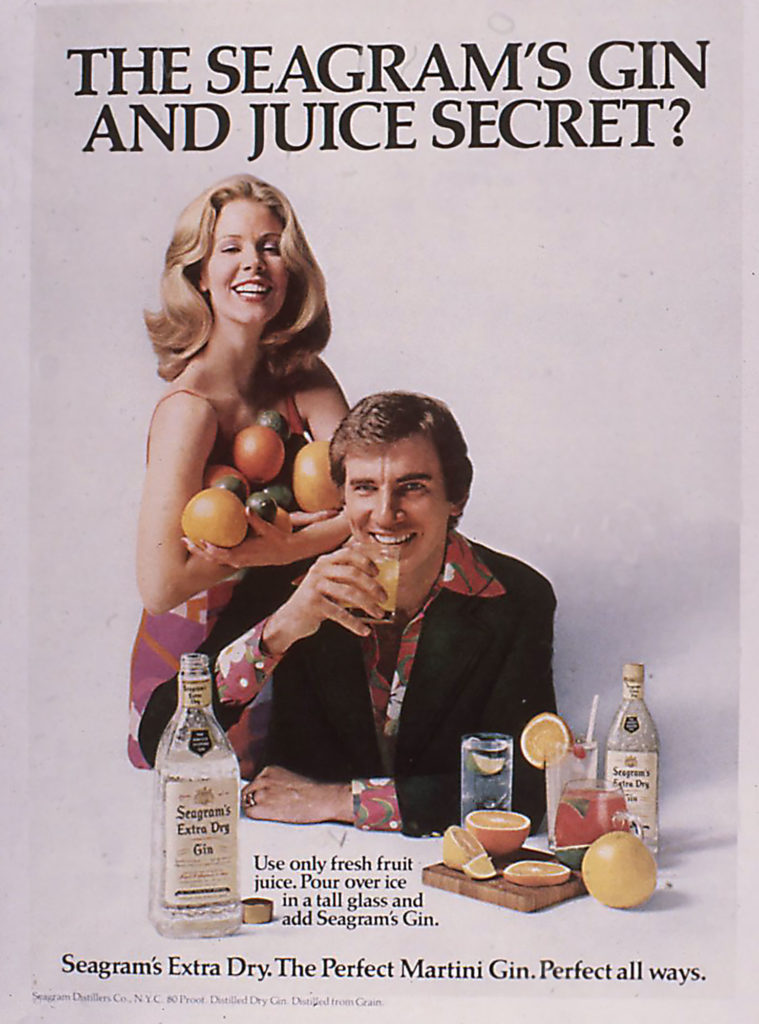

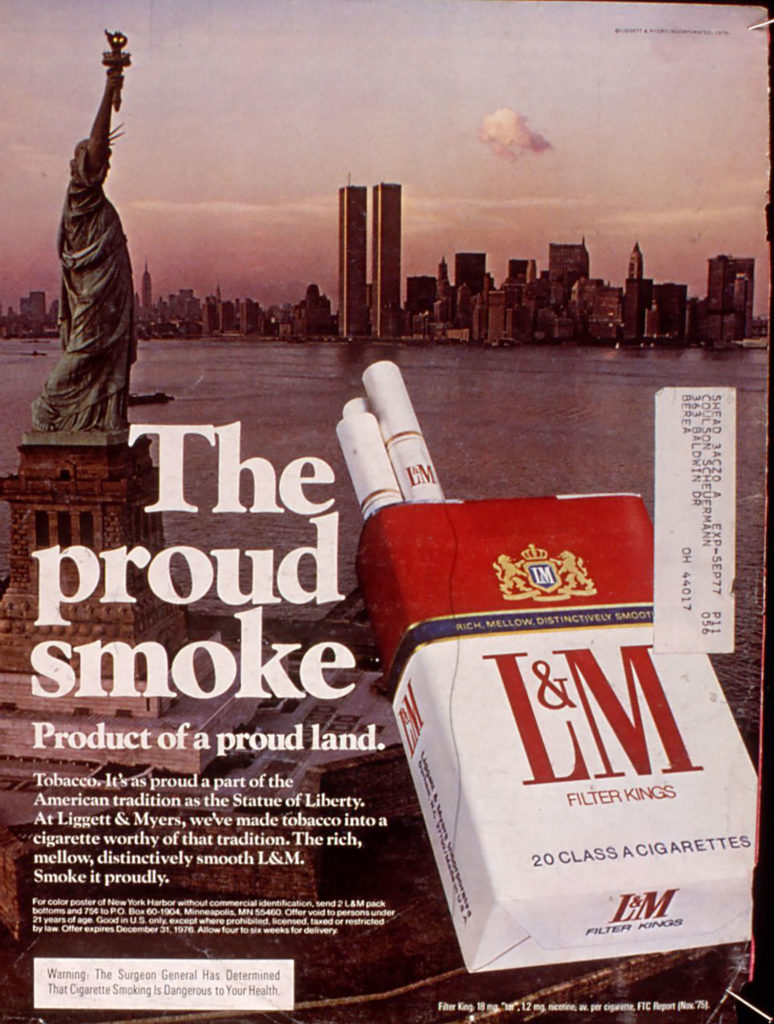

Aside from reflecting popular culture, Pop Art can be tremendously humorous in its absurdity, sarcasm and often Kitsch nature. The way in which the Pop Art of the sixties and seventies has become a part of everyday life in our culture is a testament to our enduring love for the sensibilities of this movement.

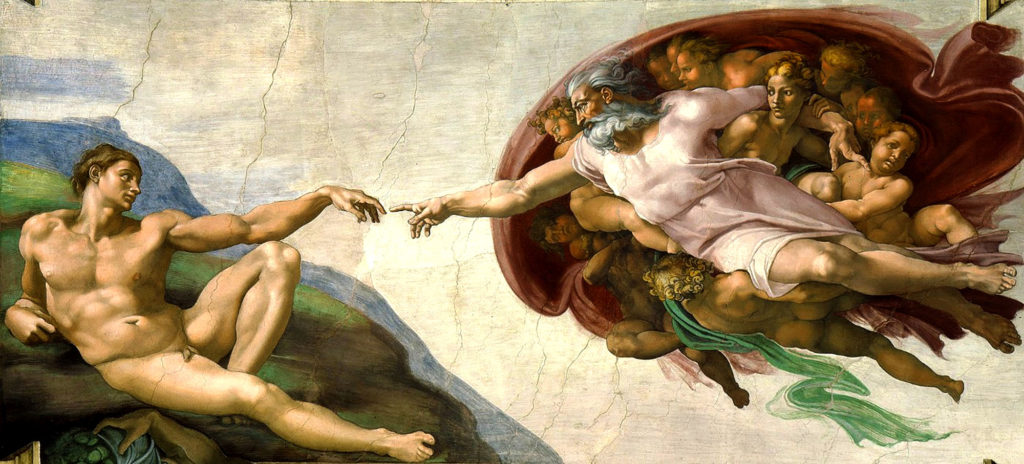

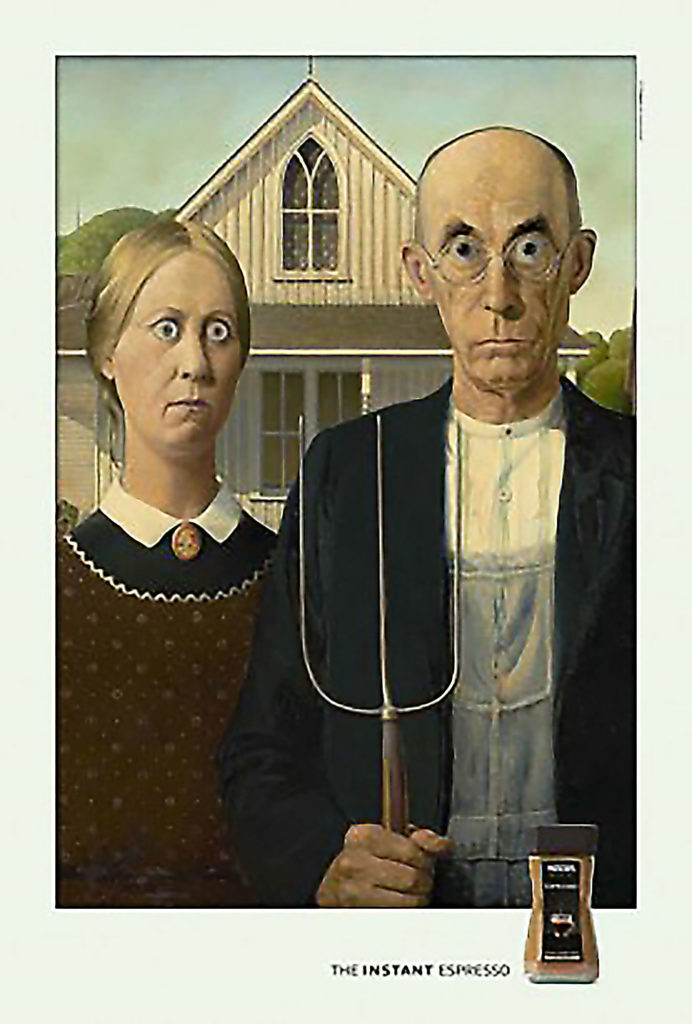

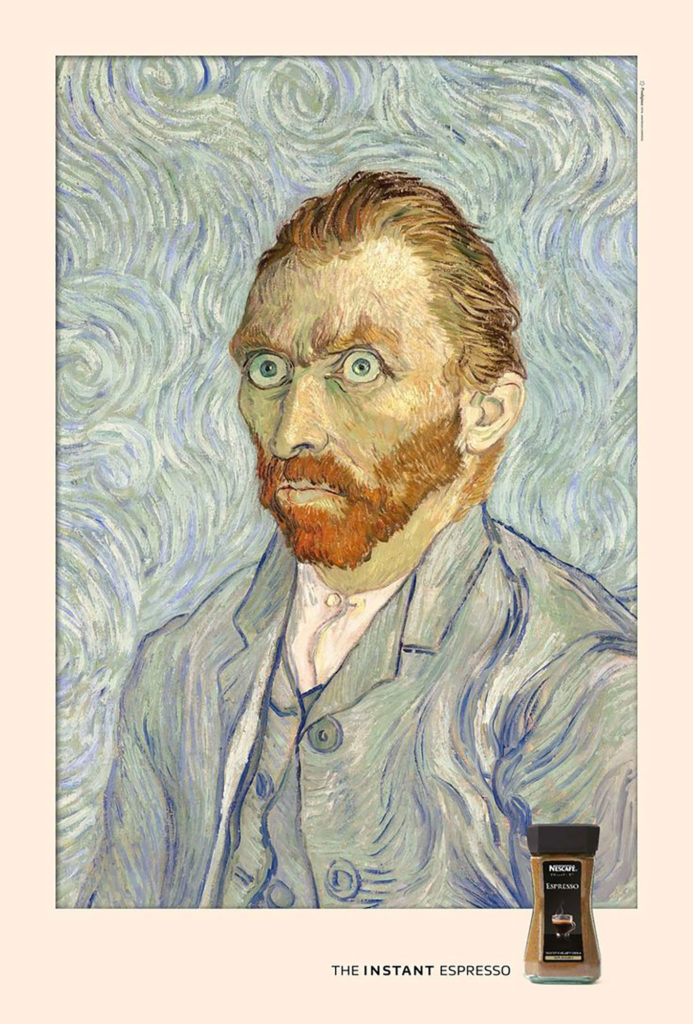

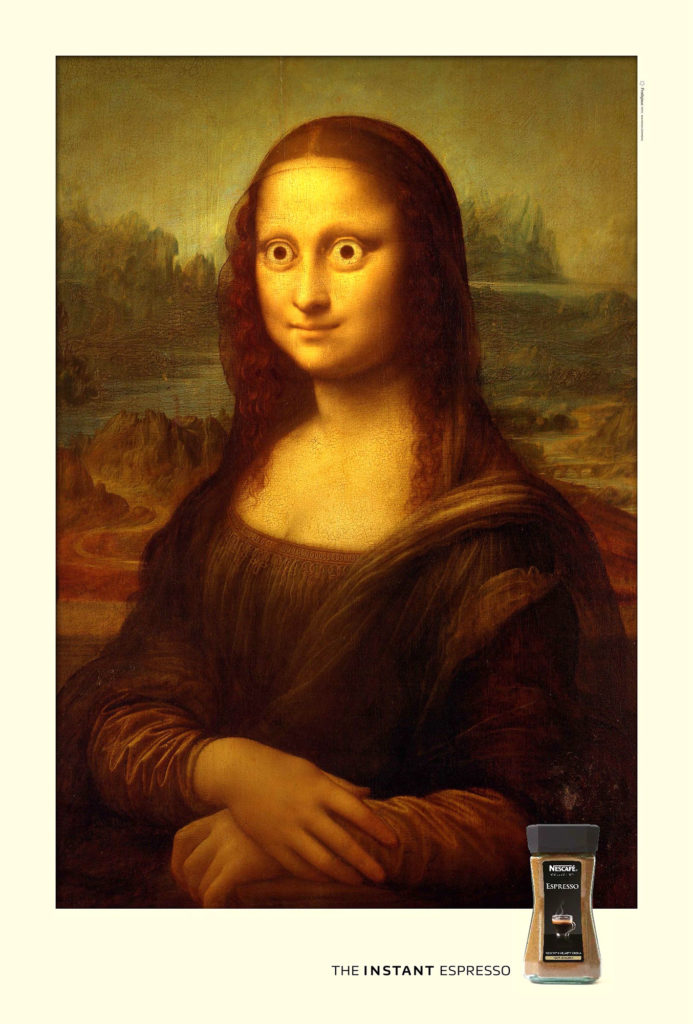

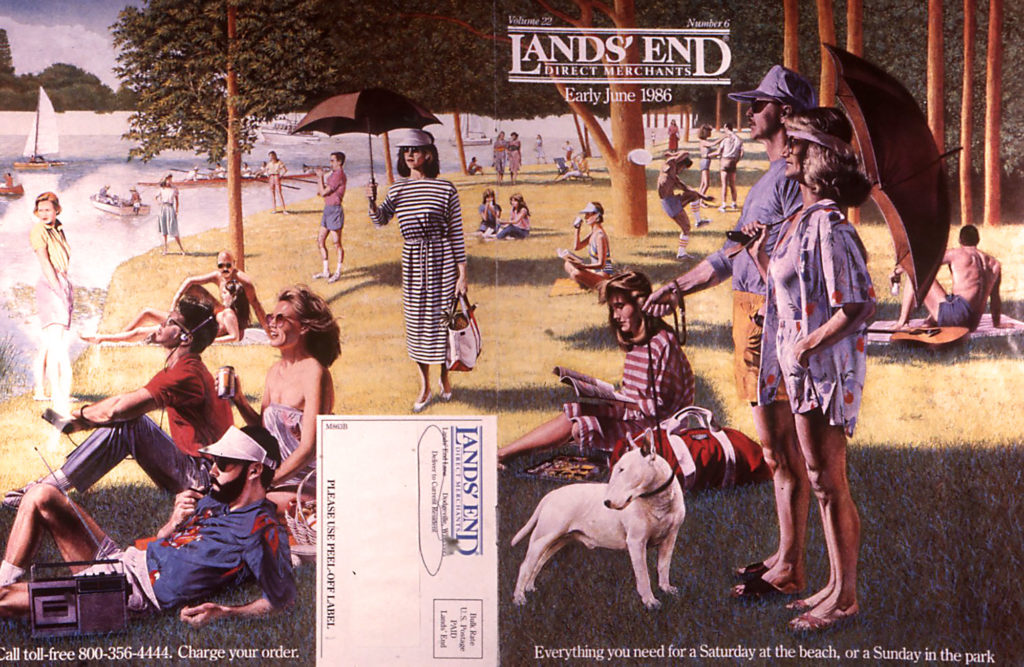

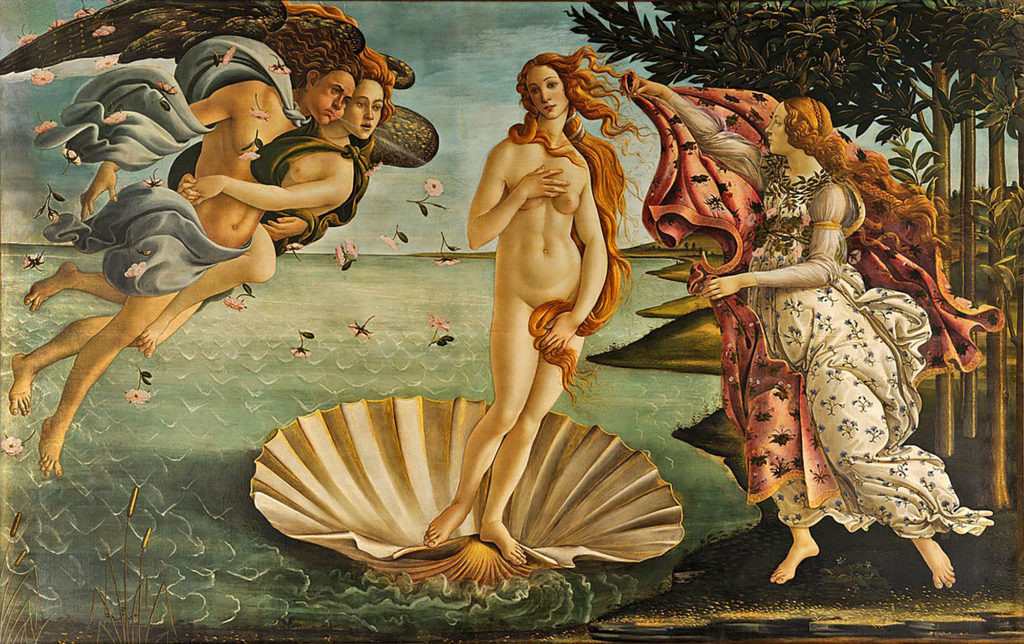

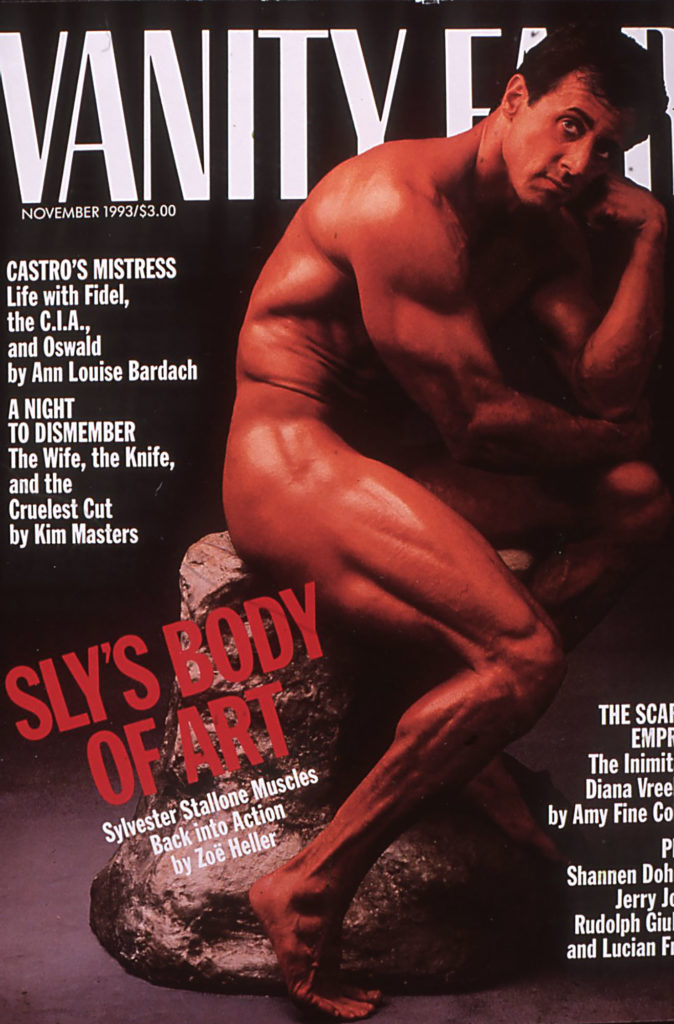

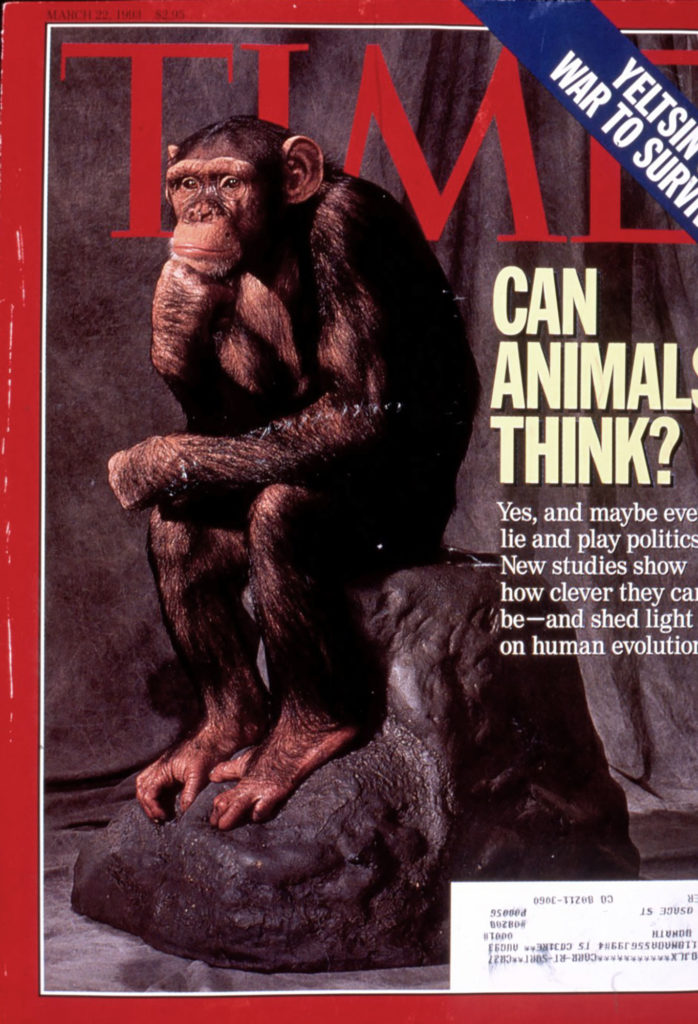

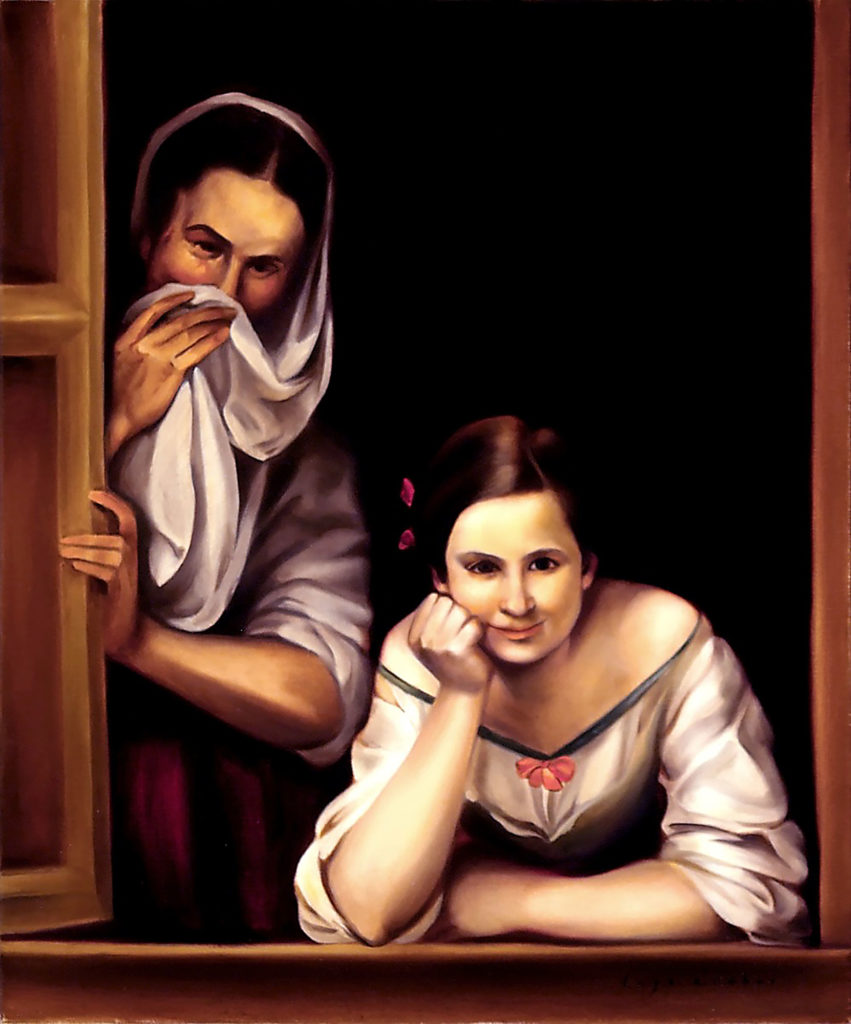

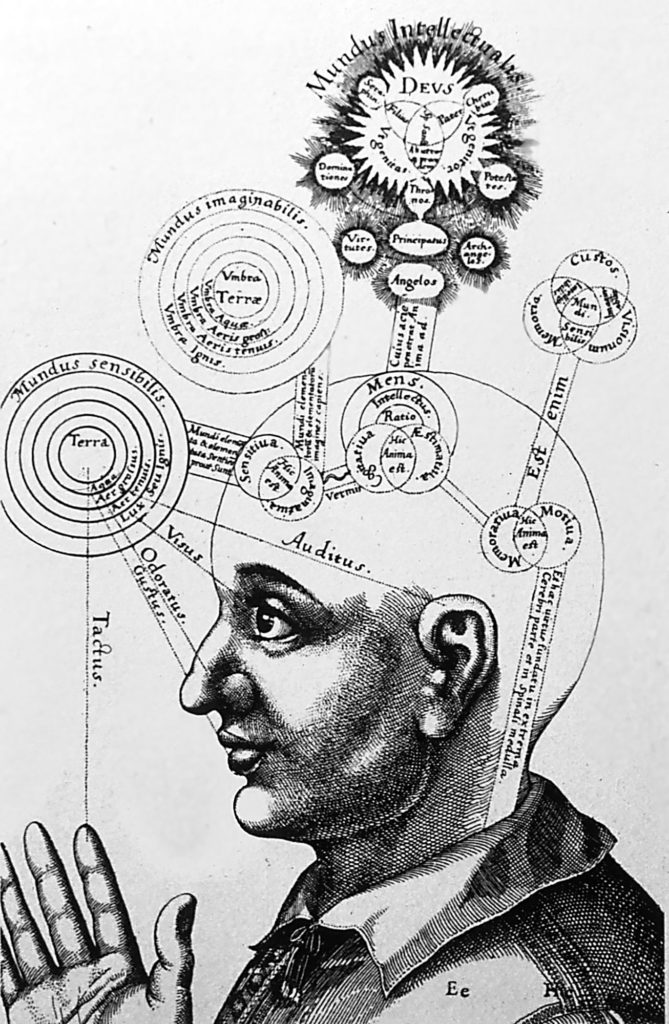

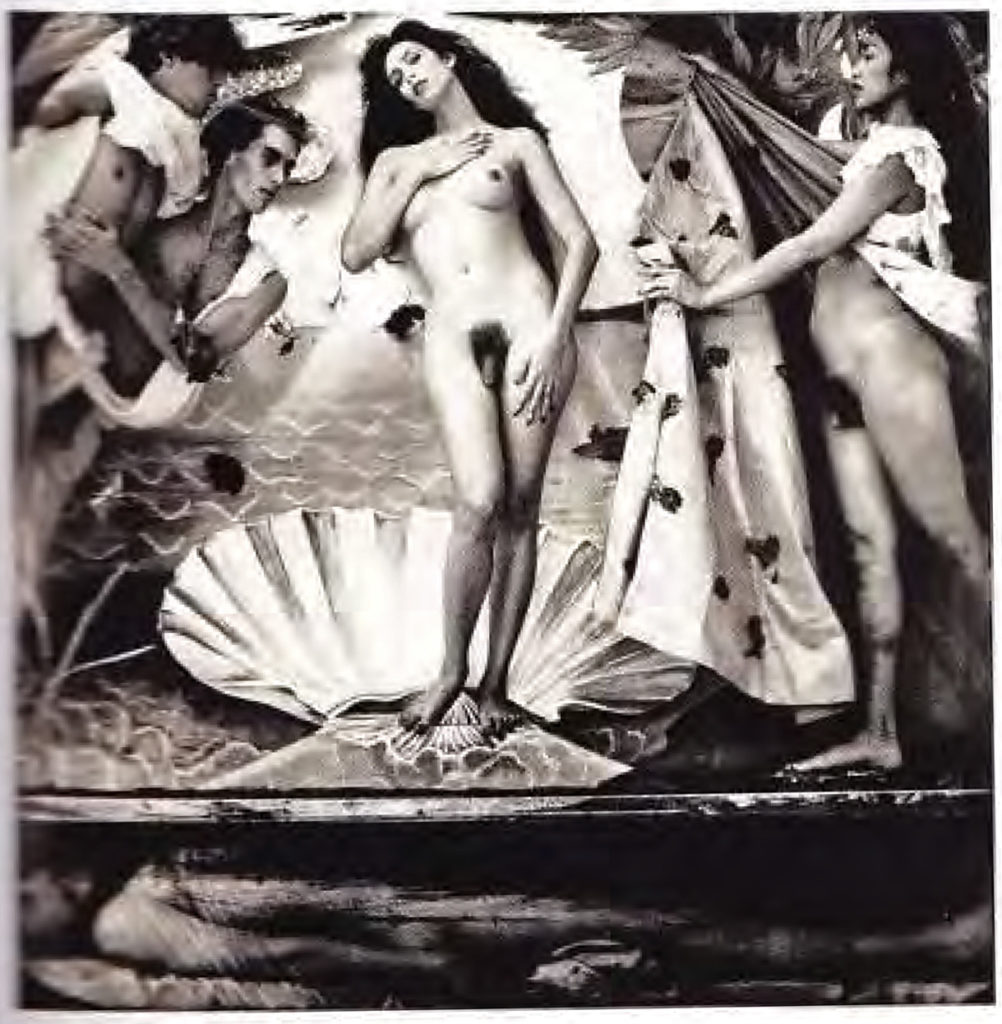

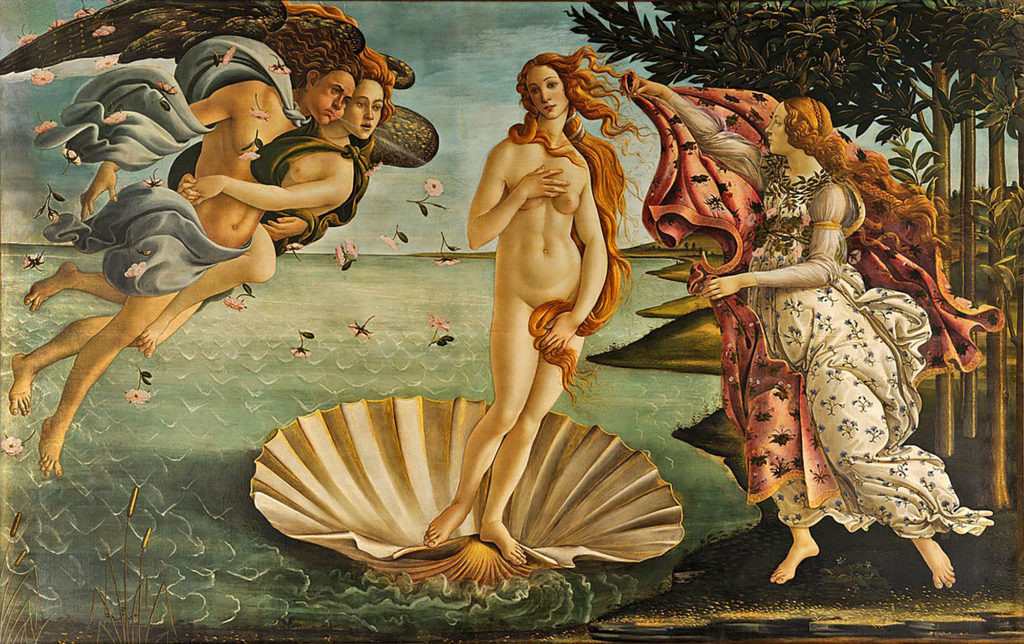

Parody is a genre of humor that is frequently found in art. Parody pokes humorous reference at iconic images that we, as a culture, are familiar with. Along with the images that we are bombarded with through media, art history provides a plethora of fodder for the parody. The most overused parodies from art history include the Mono Lisa and Michelangelo’s “Birth of Adam”, (where the finger of a muscular, white-bearded male God is almost touching the finger of our sensually gazing Adam under the pretext that God is giving the spark of life to the first man and thus giving birth to the human race. God is also surrounded by little naked nymphs, like the brain in a human skull.) Such iconic images are also exploited prolifically in commercial advertising. Parody is dependent on the reference-image being well-known in the mind of the target audience. It is often the case that the audience who “gets” the parody can be a limited audience. The parody is often a one-liner with an irreverent take on the original, but it is more often used as a humorous vehicle to carry an ulterior message.

“The parody is often a one-liner with an irreverent take on the original, but it is more often used as a humorous vehicle to carry an ulterior message.”

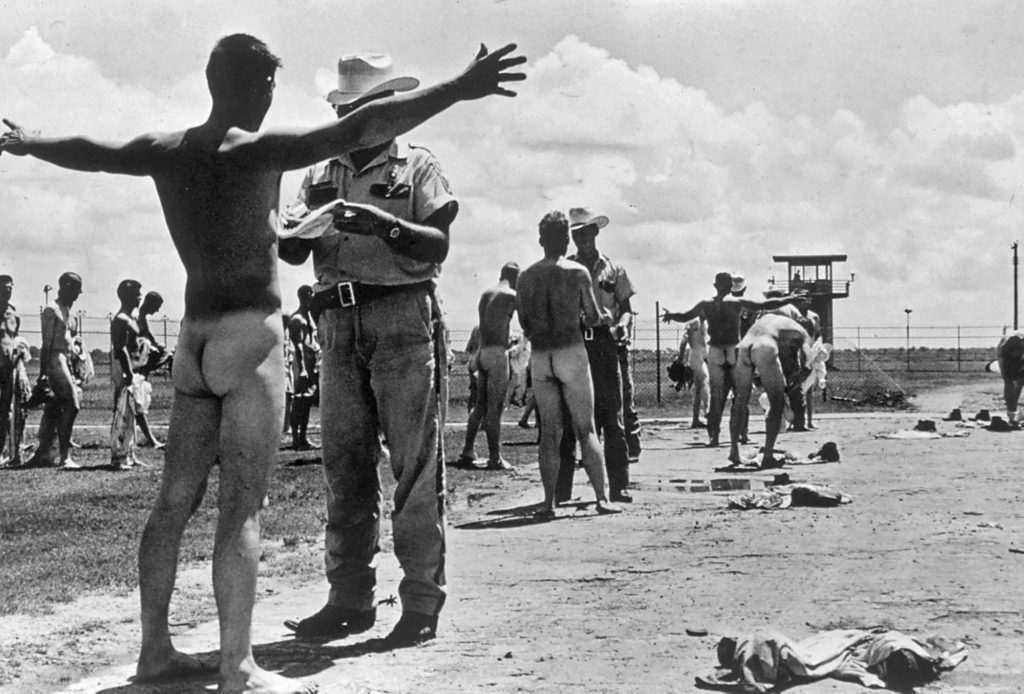

The crucifixion of Jesus is perhaps the most seen icon in our culture and is used quite often as a layer of reference in art. I make the case, that with any form of parody, there is a form of absurd humor somewhere in the means used to make a statement or raise a question. In this image a parody is used to see the prisoner as human in an epic sense and in a martyred light. The exact meaning of this lyrical proposition is for each individual to answer in their own way. Humor need not be in the end experience but can be a part of the means by which we arrive there.

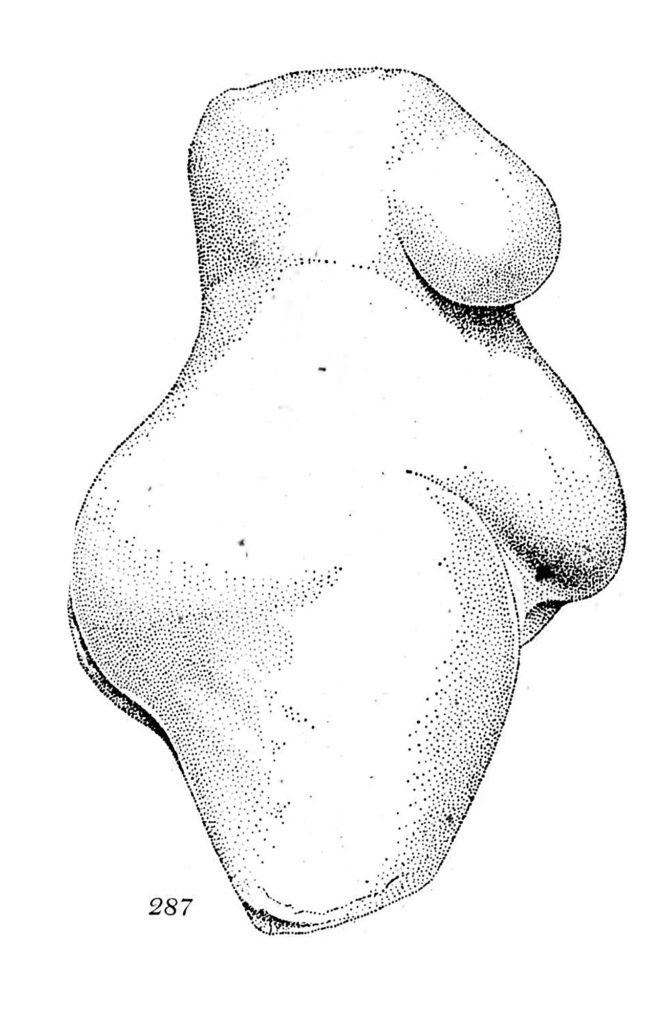

The deflated state of the balloons in this image is part of the Jeff Koons parody commentary, but aside from that, reminded me of the forms in prehistoric fertility figures like the Venus of Willendorf in which the important female reproductive parts are huge and all other features are tiny or absent – so I titled it “Venus” and laid flowers at her “feet” as a dysfunctional fertility offering of sorts.

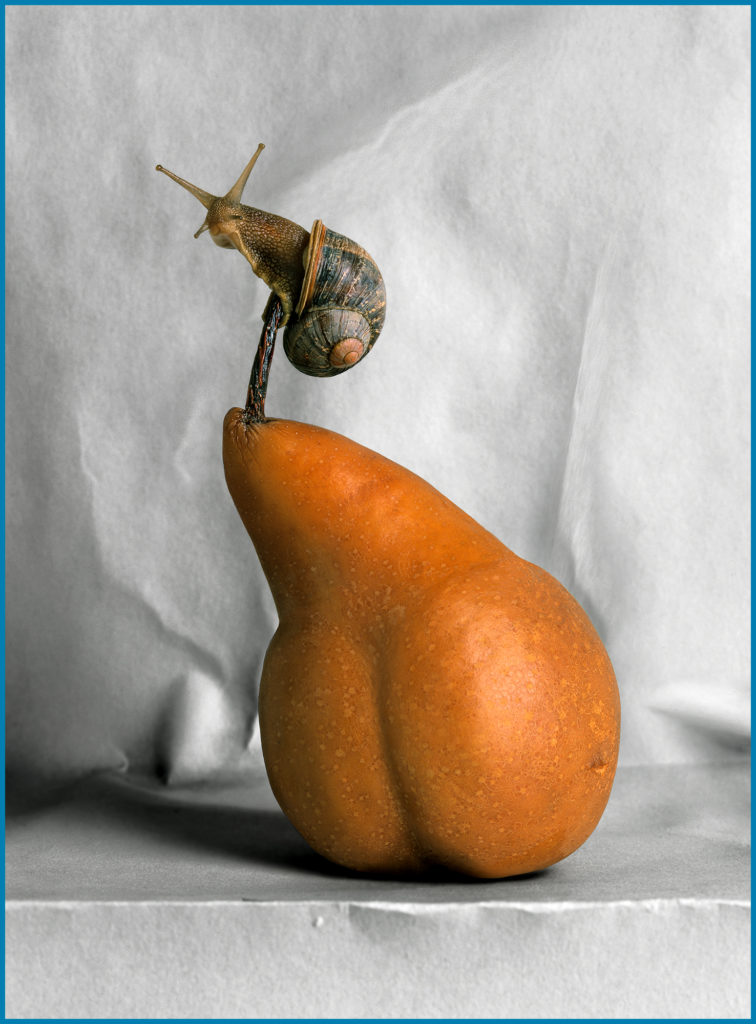

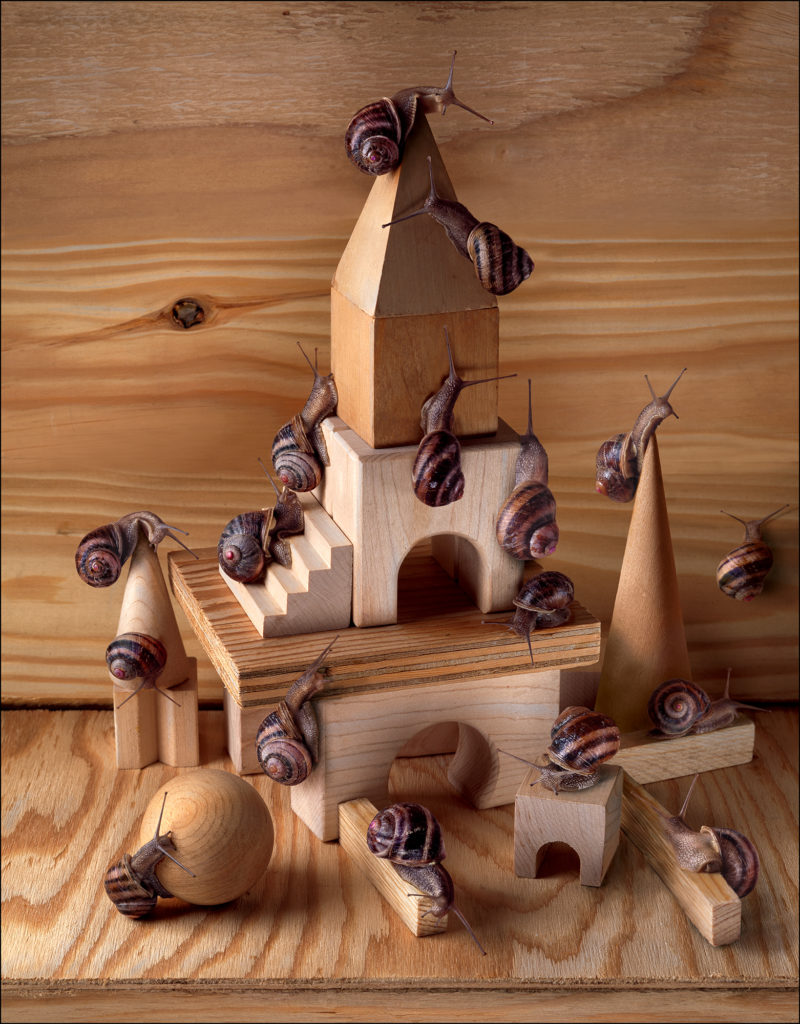

Magic Realism can be seen as a genre of Surrealism. (This genre is more commonly referred to in writing.) Magic Realism imbues the mundane with a magical level of reality. I use it to transform everyday objects, often with a humorous perspective. Magic Realism can be a catalyst or bridge to engage in meaning where we least expect it. The psychology of Magic Realism embodies the maxim that there is more to reality than what appears on the surface; images can be read in a way that includes, yet transcends, the simple identity of an object.

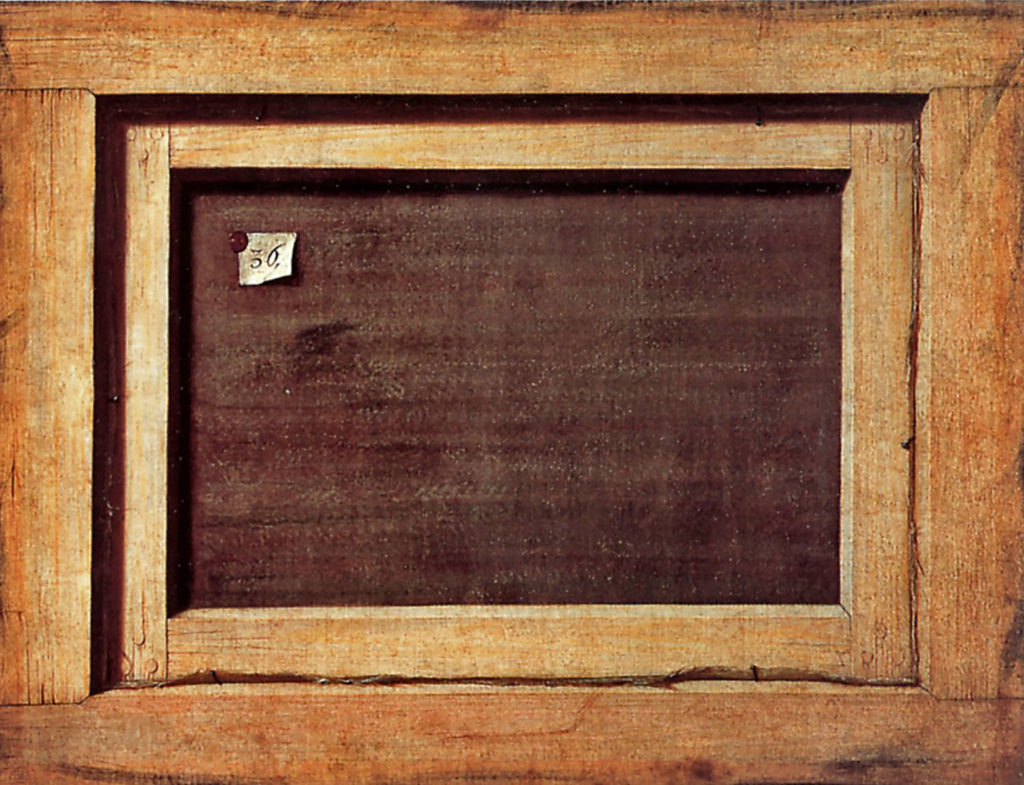

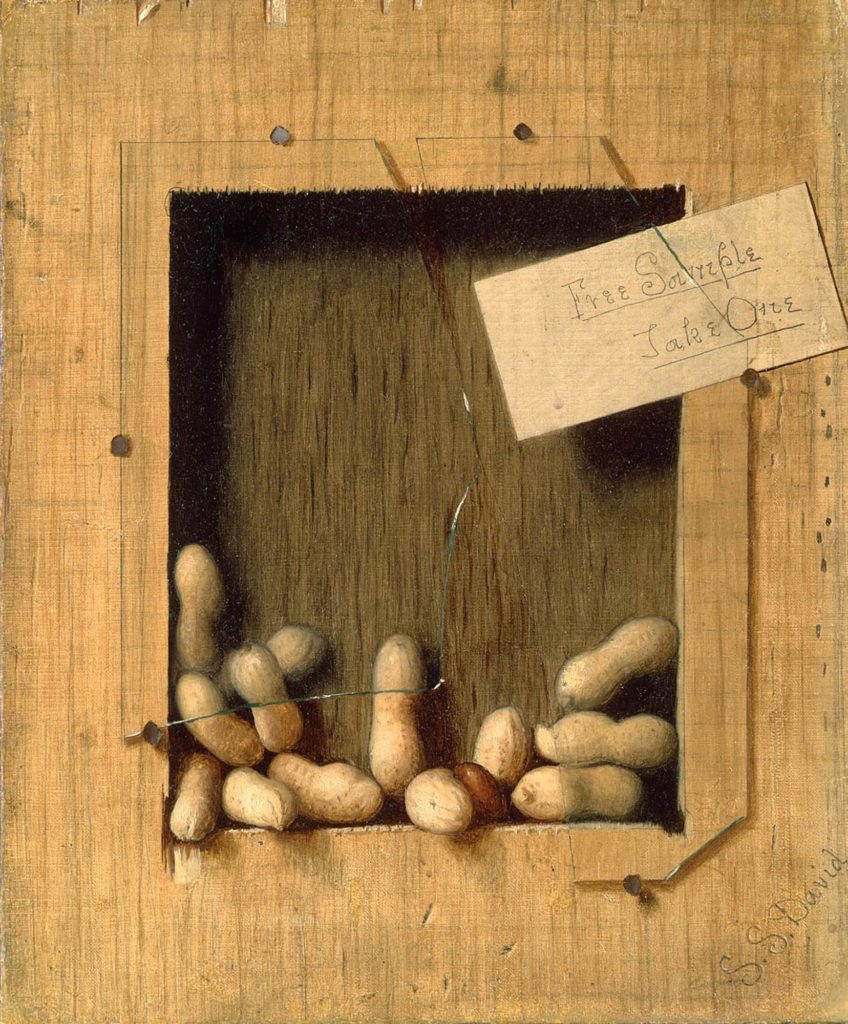

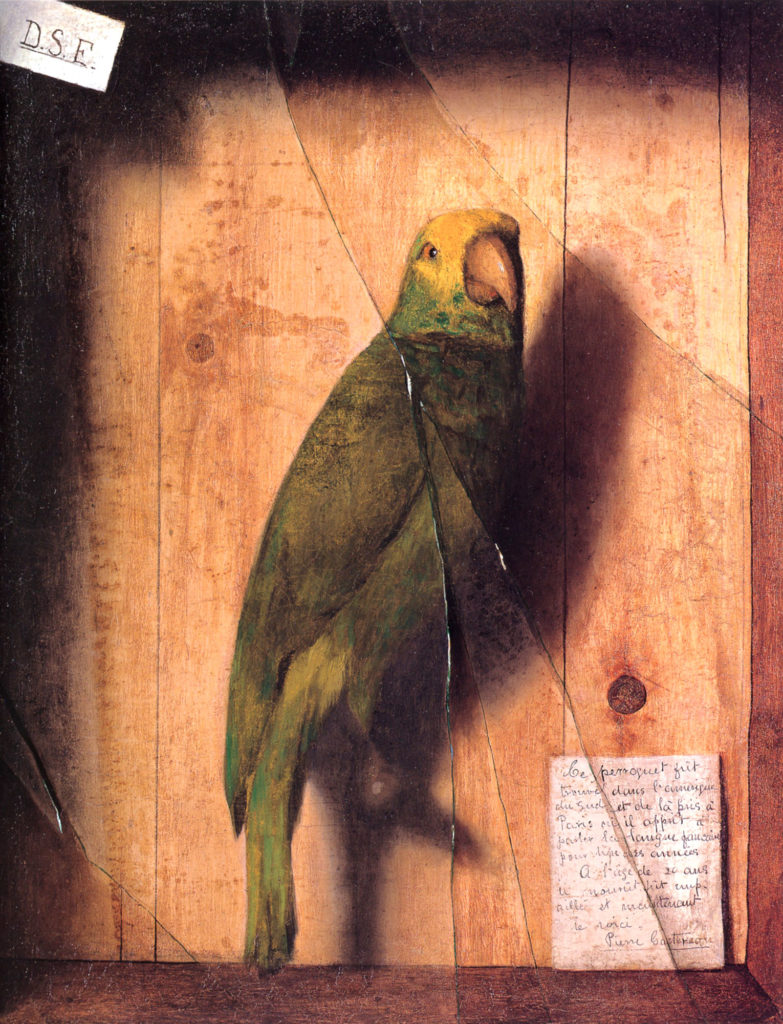

“Trompe l’oeil” (“deceives the eye”) is a unique genre of art that humorously plays with our perceptions. In this genre, the illusion is perceived as denying its own two-dimensional surface and existing in the logic of the three-dimensional space in which the viewer exists. In order to perceive the illusion, there is a specific vantage point from which the work needs to be viewed. The idea is slightly different in Tromp l’oeil sculpture where it is hard to believe what is in front of our eyes as we assume the object is other than what it is.

In this piece, the content is not humorous but the delivery is a Tromp l’oeil pun. 2-D becomes 3-D when the image literally breaks out of the confines of the picture plane and frame as some frogs jump through the frame, some sit on the frame, while one escapes onto the wall. I painted the frame with cracks to replicate the mud cracks and wet/dry patterning in the photograph. The hands are casts of the same hands that are in the photo.

German street painter Edgar Mueller is a master of playful Trompe l’oeil street art. People know this Trompe l’oeil crevasse isn’t real but that wouldn’t stop us thinking twice before standing on it. Trompe l’oeil art always plays with a perceptual conflict between what we see and what we know. There are a plethora of street artists that work in this genre, many of whom create their temporary works in chalk.

An amazing form of three-dimensional Trompe l’oeil is the fake plastic food of Japan that one sees displayed in restaurant windows in lieu of a written menu. Although it is not considered fine art, or even humorous, it is one of the highest and amusing forms of visual illusion out there and is a multi-billion dollar industry. These perfect replicas are one-of-a-kind with their hand-crafted imperfections; even fish eyes are clouded over from the heat, the markings suggest that it was flipped over the charcoal with delicate crinkles and uneven washes of carbonization. An artisan commented that the hardest illusion for him to create was the warmth of just-cooked foods – the sizzling edge of a pork cutlet right out of the pan and the steam escaping from a bowl of rice. These obsessively worked over plastic food models are known as shokuhin sampuru (translated as “foodstuff samples”, “sampuru” being the Japanese pronunciation of the English word “sample”). With some single plate replicas selling for $17,000 each, many restaurants end up renting them.

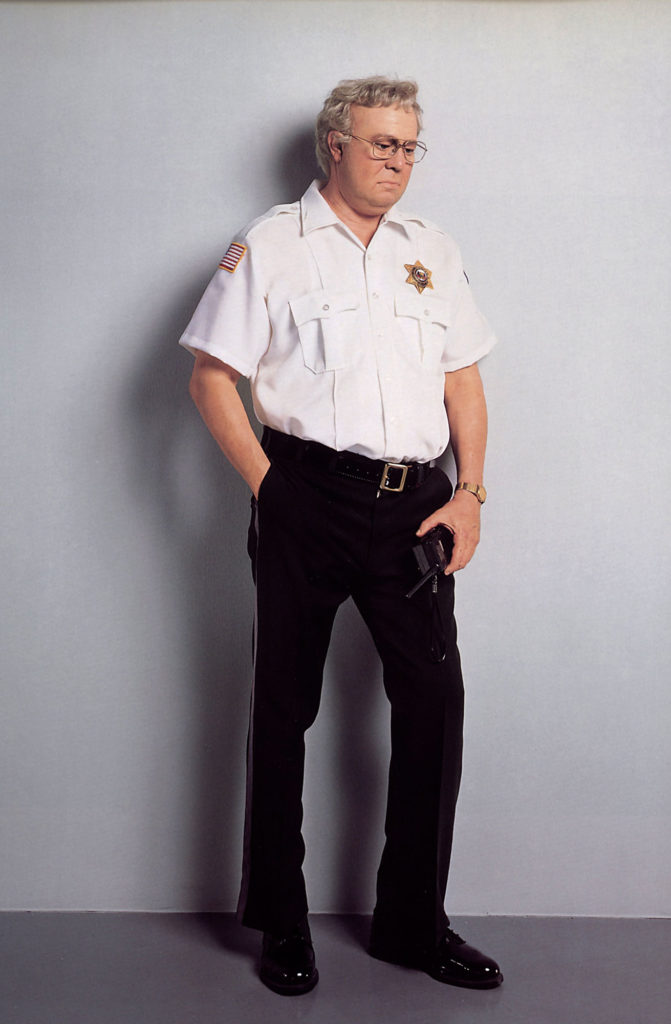

The established genre titles of art movements do not have definite boundaries and quite frequently, art crosses borders and overlaps into multiple categories of classification. Here are some Pop Art examples that are also Tromp l’oeil.

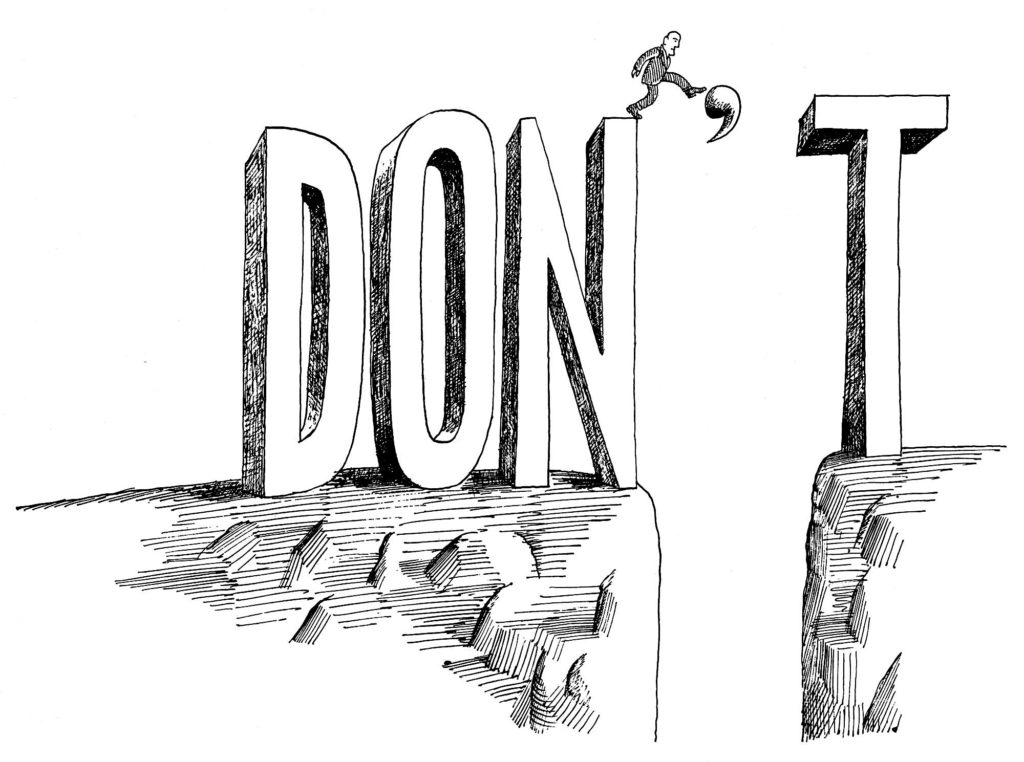

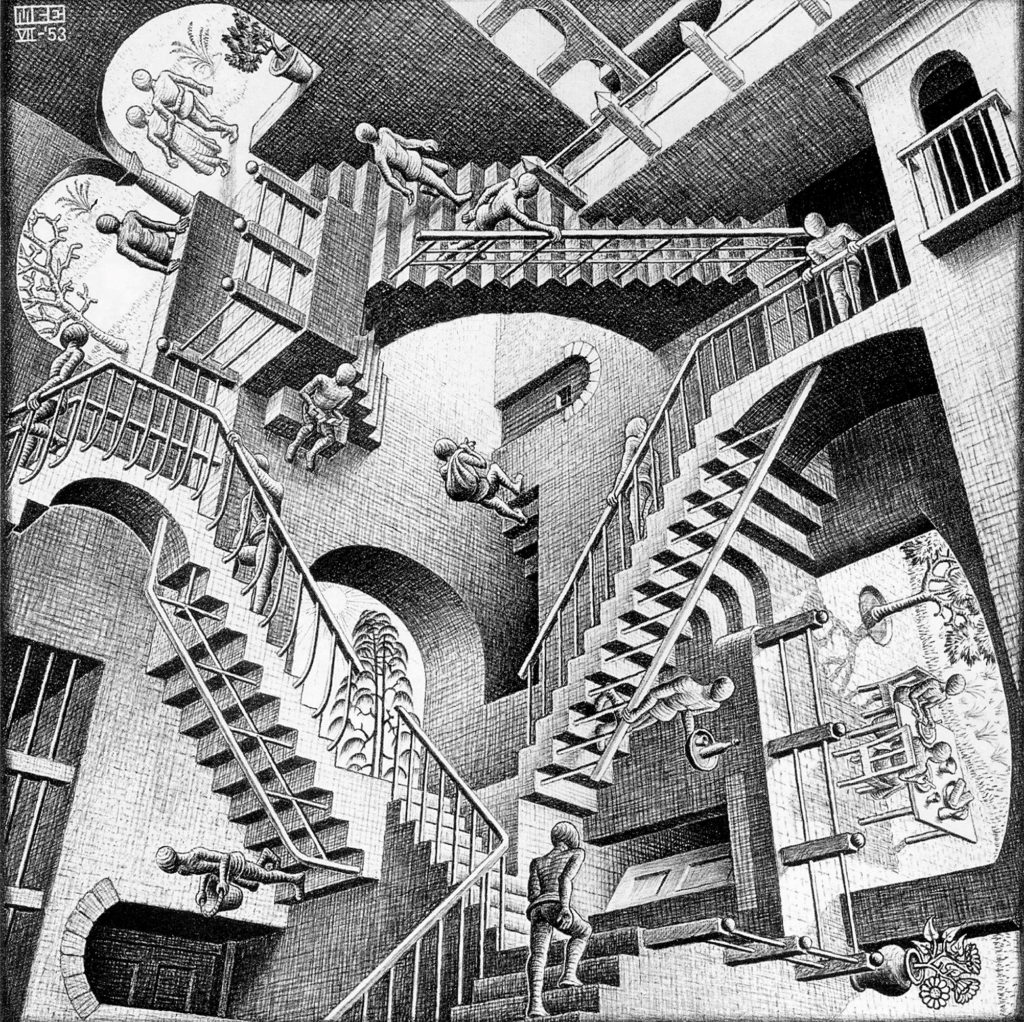

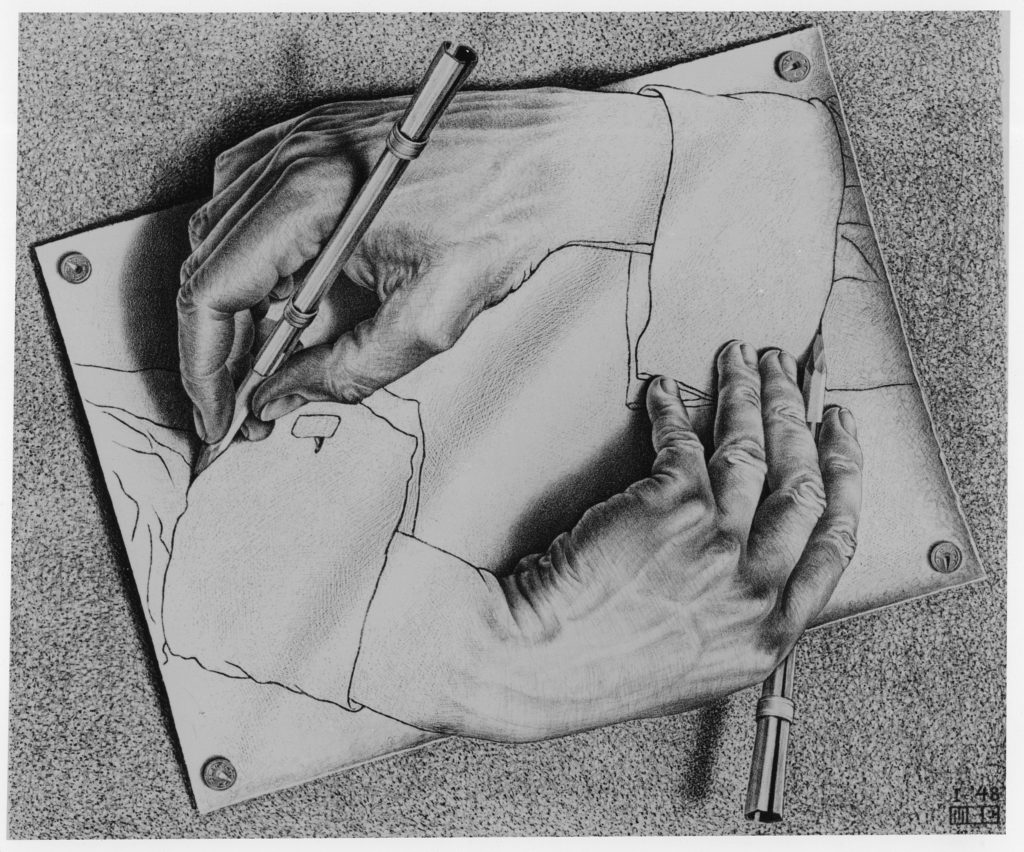

There is one particular kind of visual humor that is my favorite but has no specific term that I know of to describe it. Since I see it often, I have created my own term to describe it for my own thinking. I call it “esoteric media humor”. There are many sub-genres to this kind of humor, but they all are plays on perception; a joke about the medium vs. message. What I mean by this is that the media itself is used to make fun of itself in ways that joke about the often contradictory manner in which our brains process visual information.

Reading images is something we take for granted but is actually a complex language that had to be invented. This visual language has many rules in order for us to create and see pictures “correctly”. When the “rules” are understood, they can be broken to play games with our brains in very humorous, clever and witty ways. This perceptual genre of humor plays with the visual language we use to understand our universe. It is a world in which “seeing” and “knowing” are at odds. “Seeing” is usually the stronger of the two and wrongly wins the battle to understand what is in front of us, even though we “know” it to not be so. “Esoteric media humor” has fun with breaking the “rules” of perception.

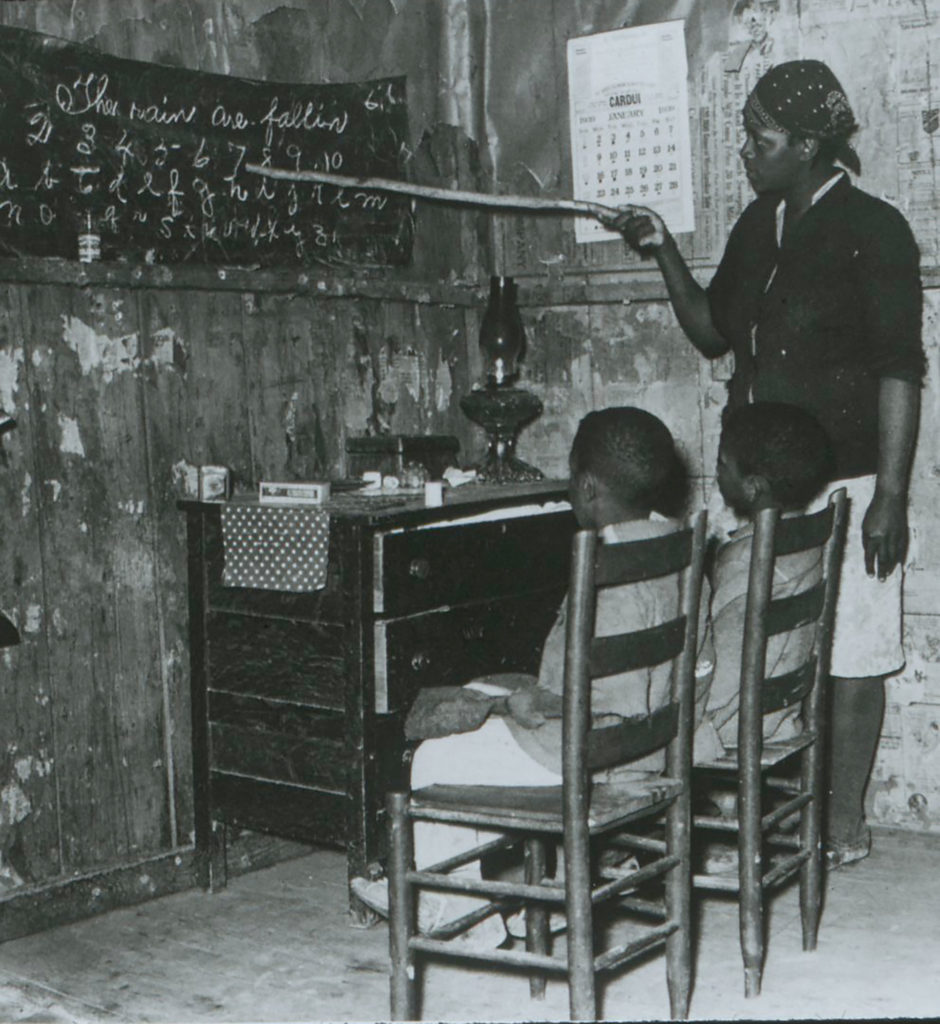

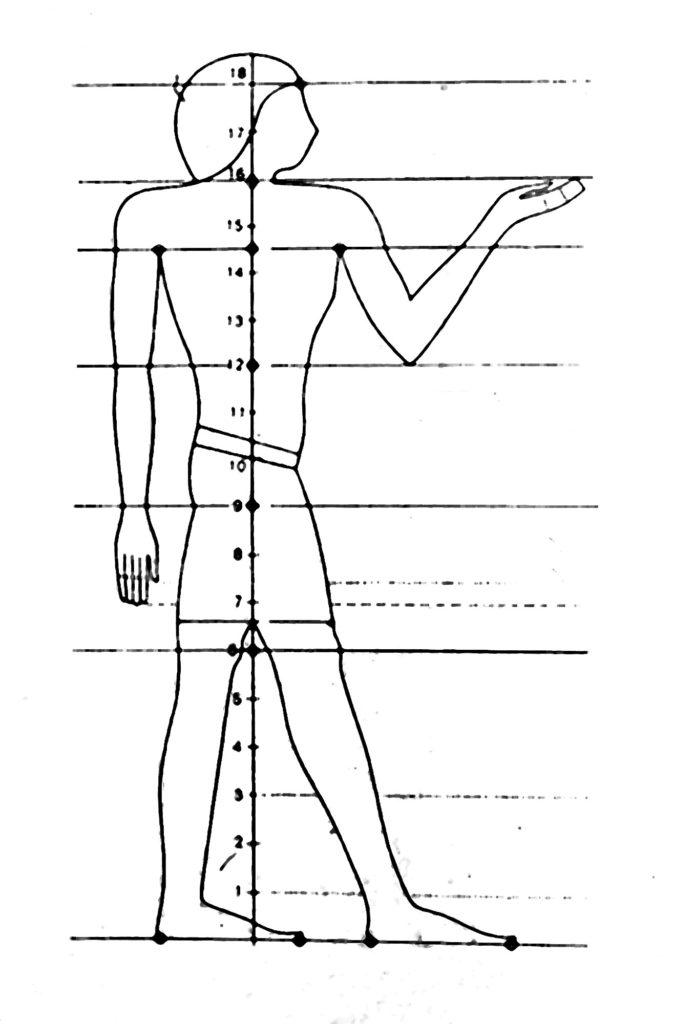

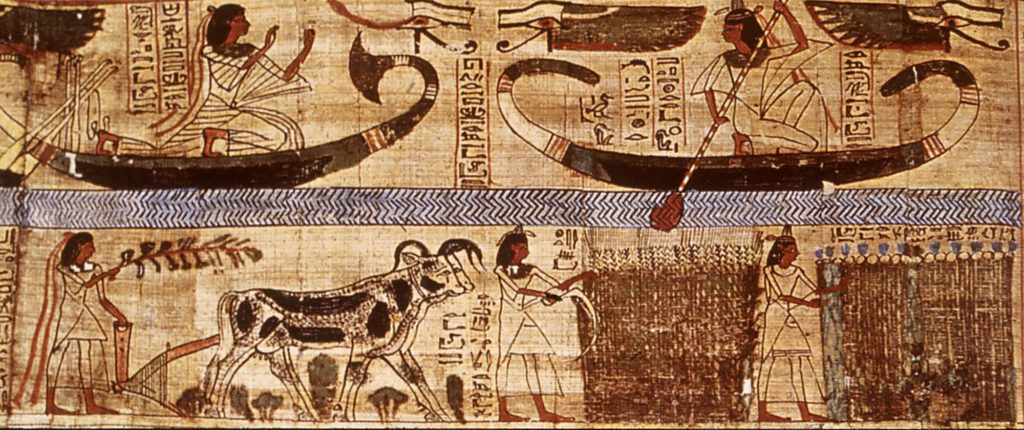

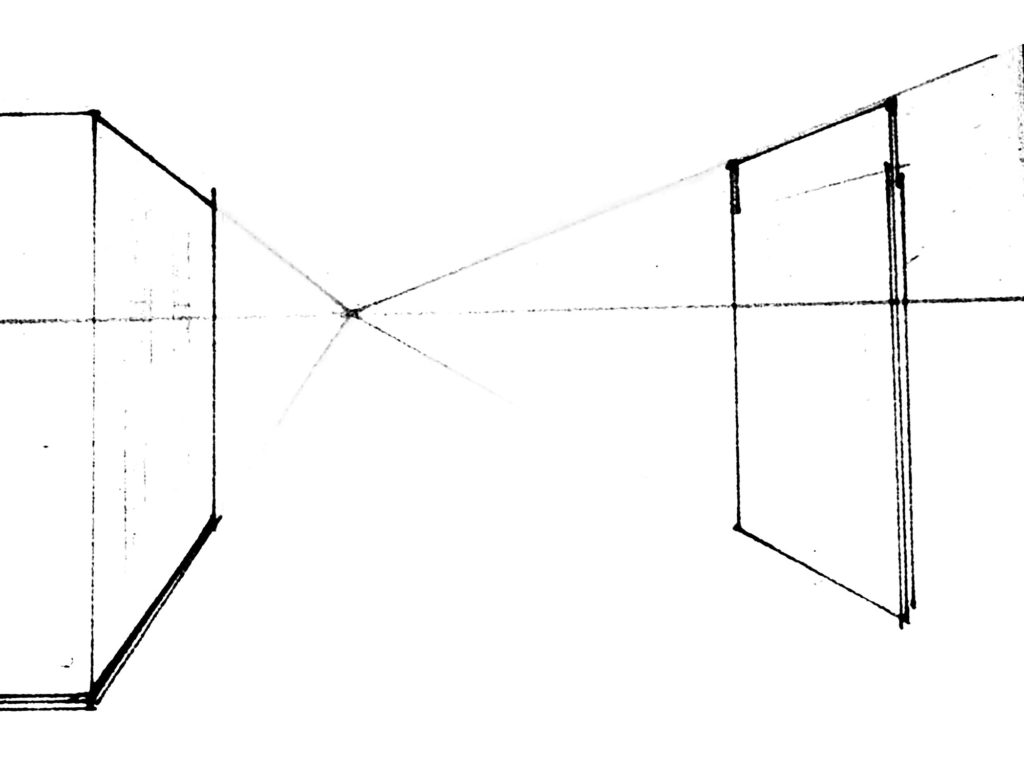

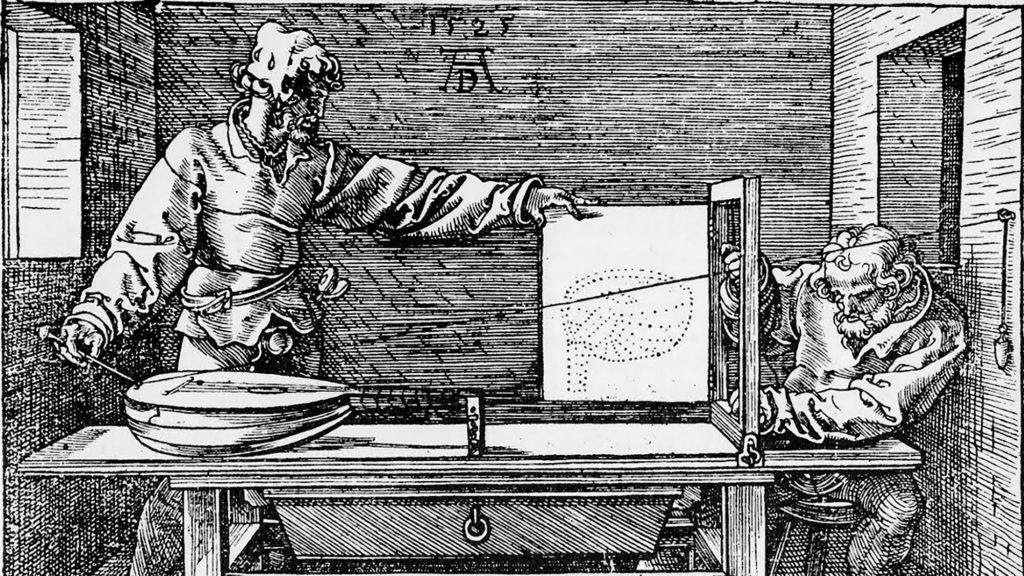

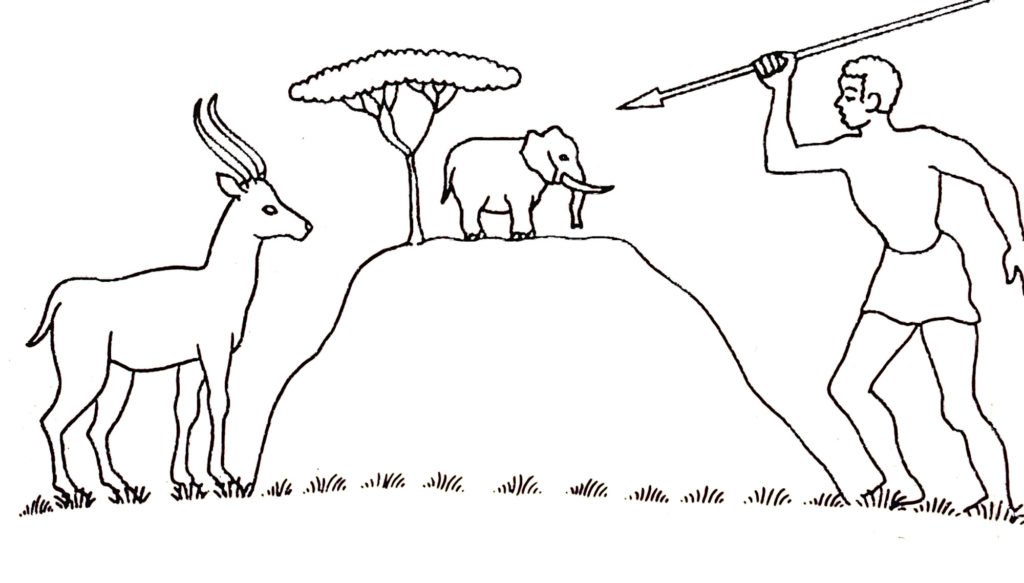

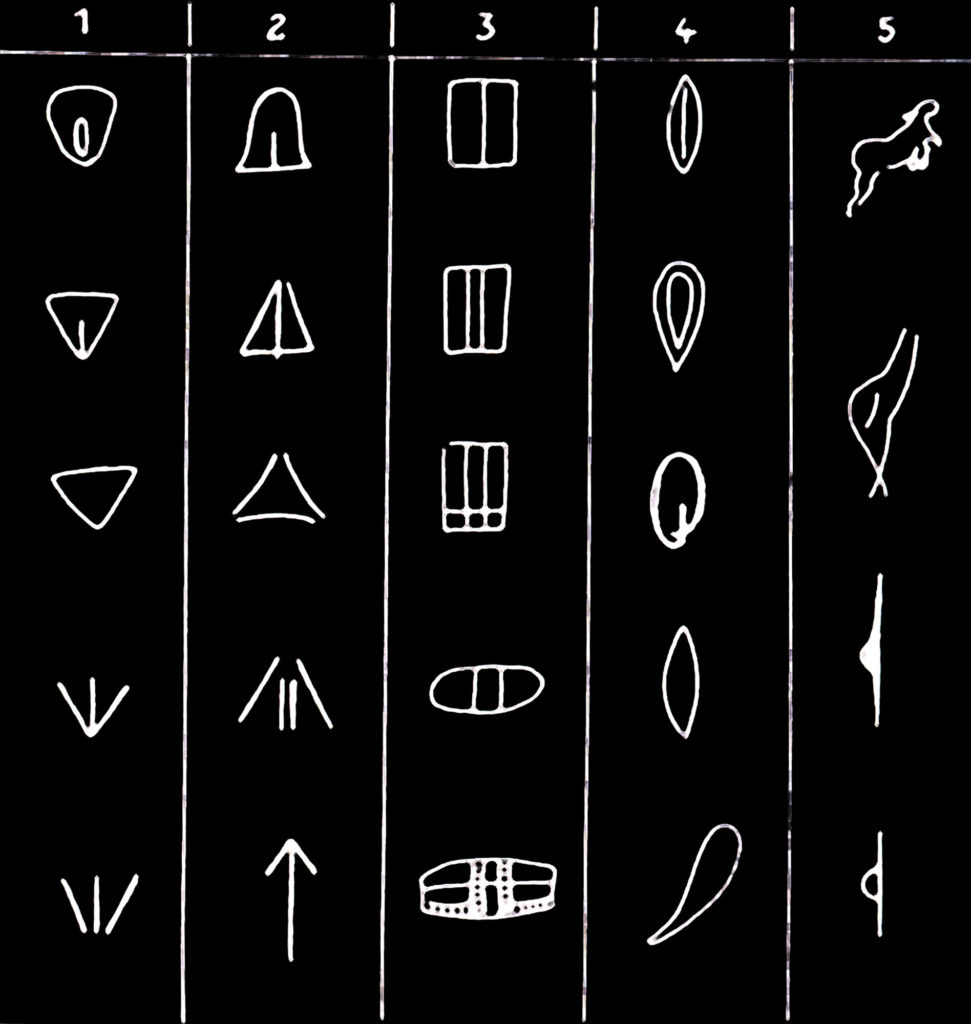

Drawing techniques that we now take for granted such as “perspective” and “foreshortening” are devices that were invented during the European Renaissance in the early 1400’s. That’s quite recent in a historical timeline. Back 3,000 years ago, Ancient Egypt had different “rules” in their mark-making systems that denoted meanings different from what we use today. For example, if someone were considerably larger than another person, it did not denote that they were closer, it meant they were more important.

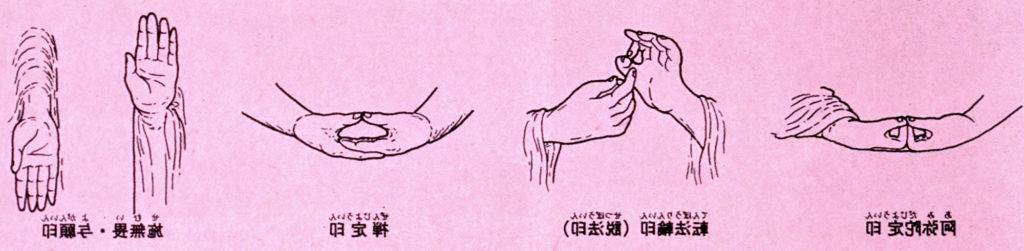

And yet a couple other mark-making systems we must learn how to visually interpret in order to understand them. One from prehistoric times and the other a system of hand gestures, called mudras, each with a particular spiritual meaning which can be read by those knowing the language.

And a few examples from the lineage of visual mark-making history that we have come to use today.

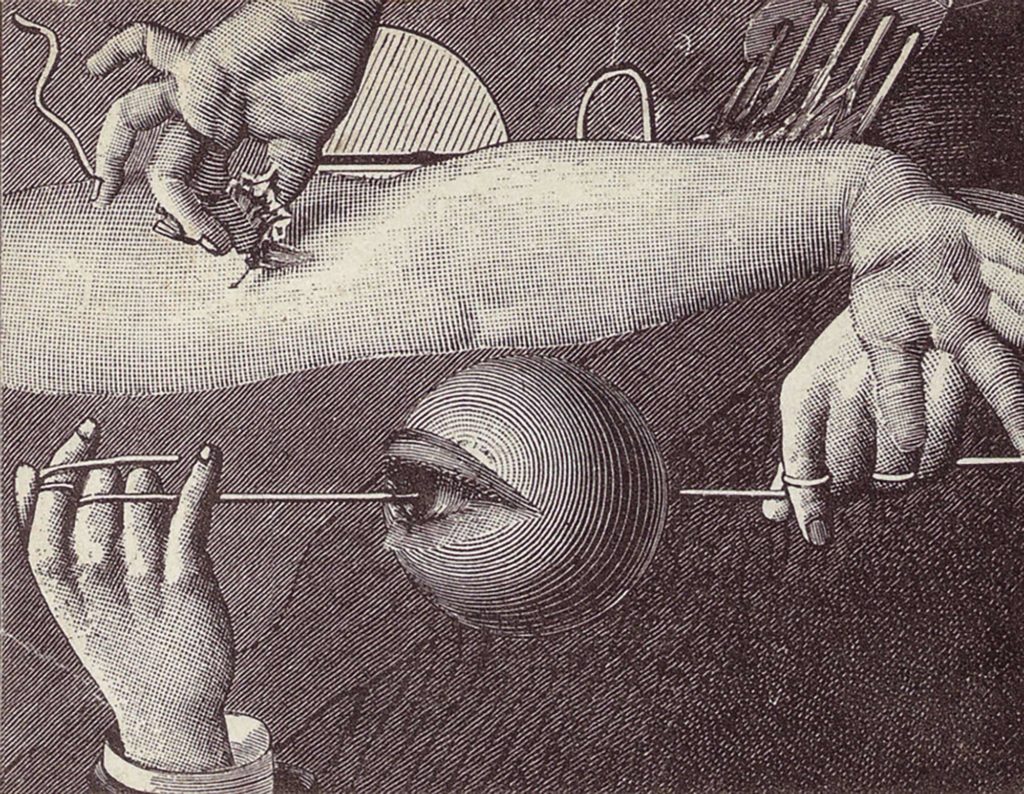

Two masters of foreshortening (the illusion of human anatomy coming forward in space)

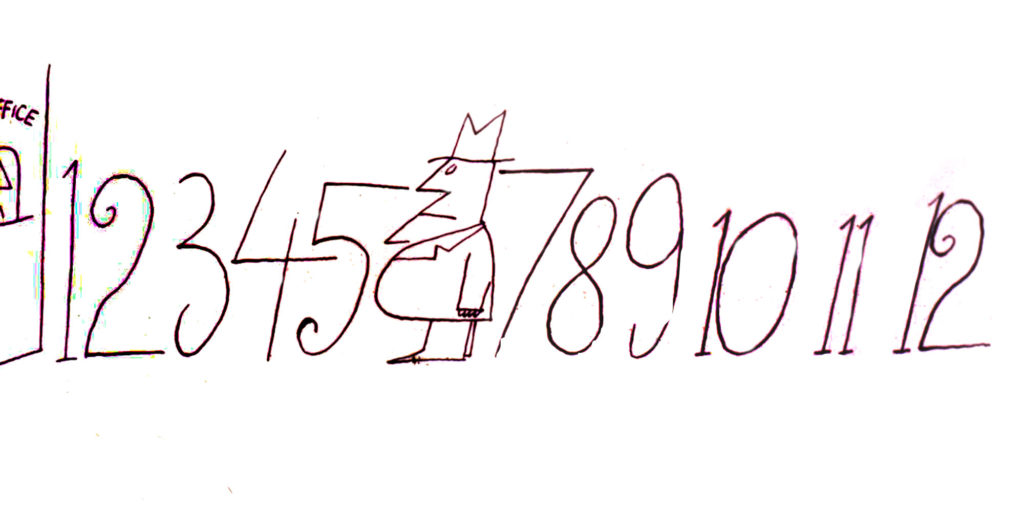

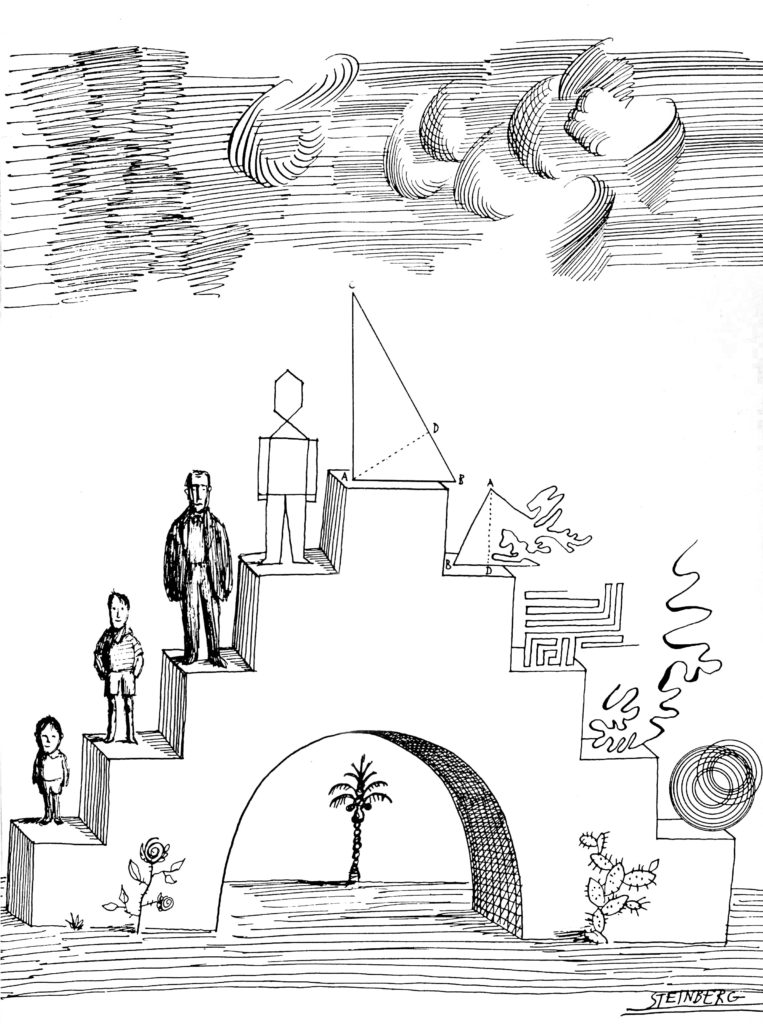

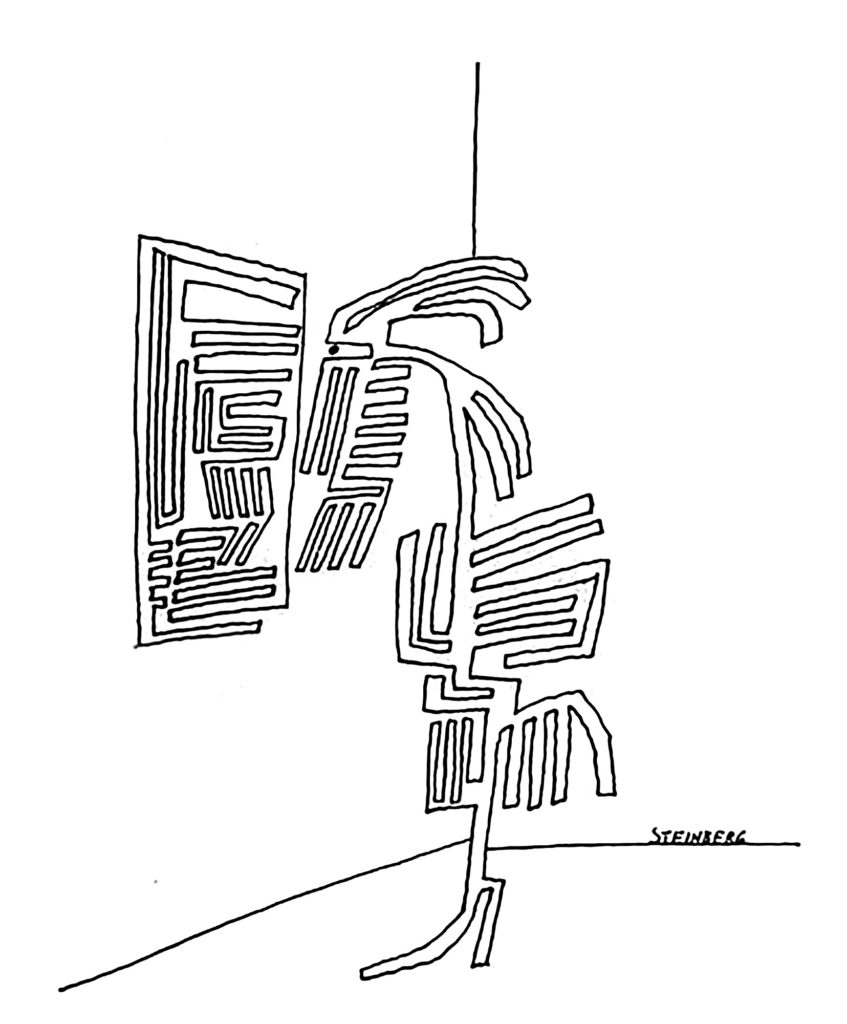

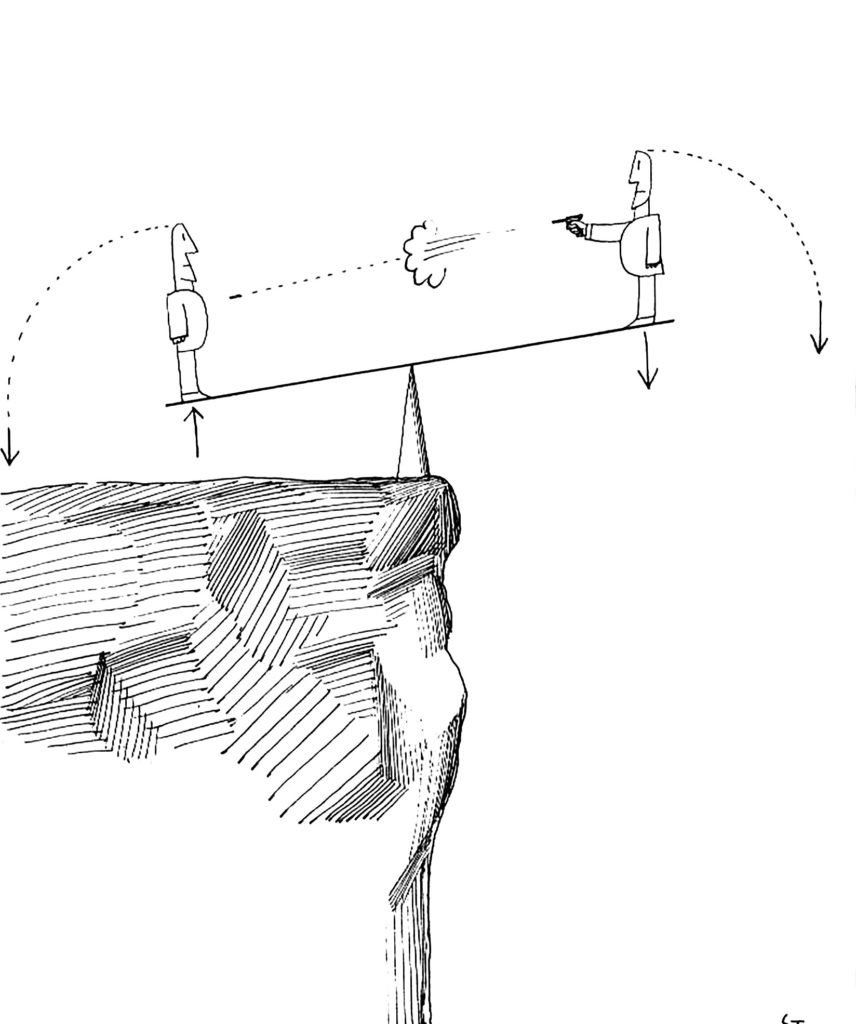

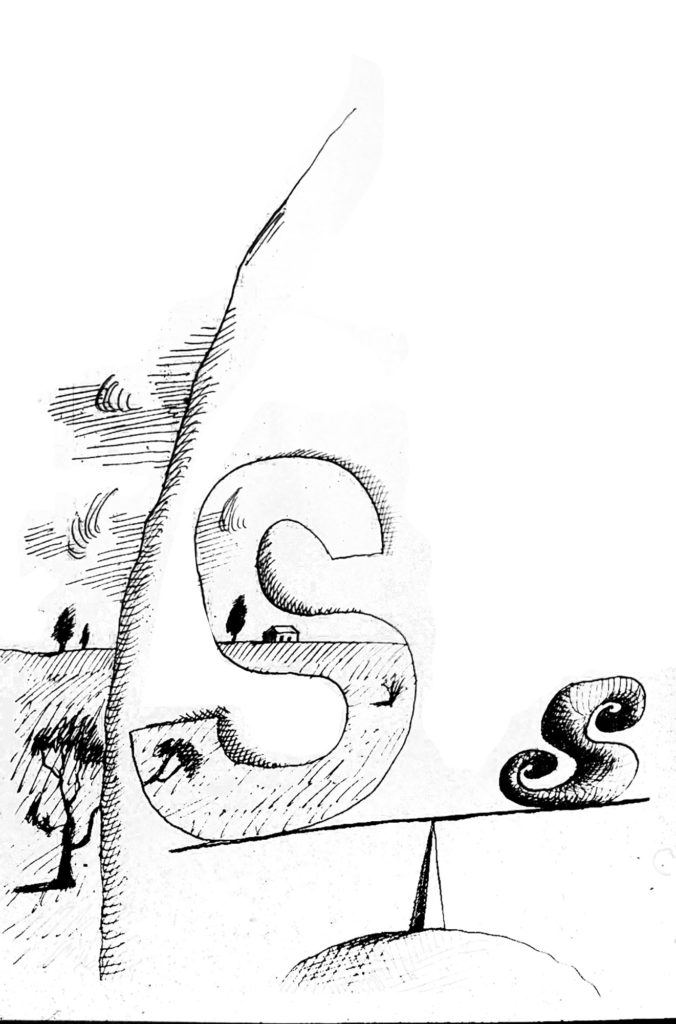

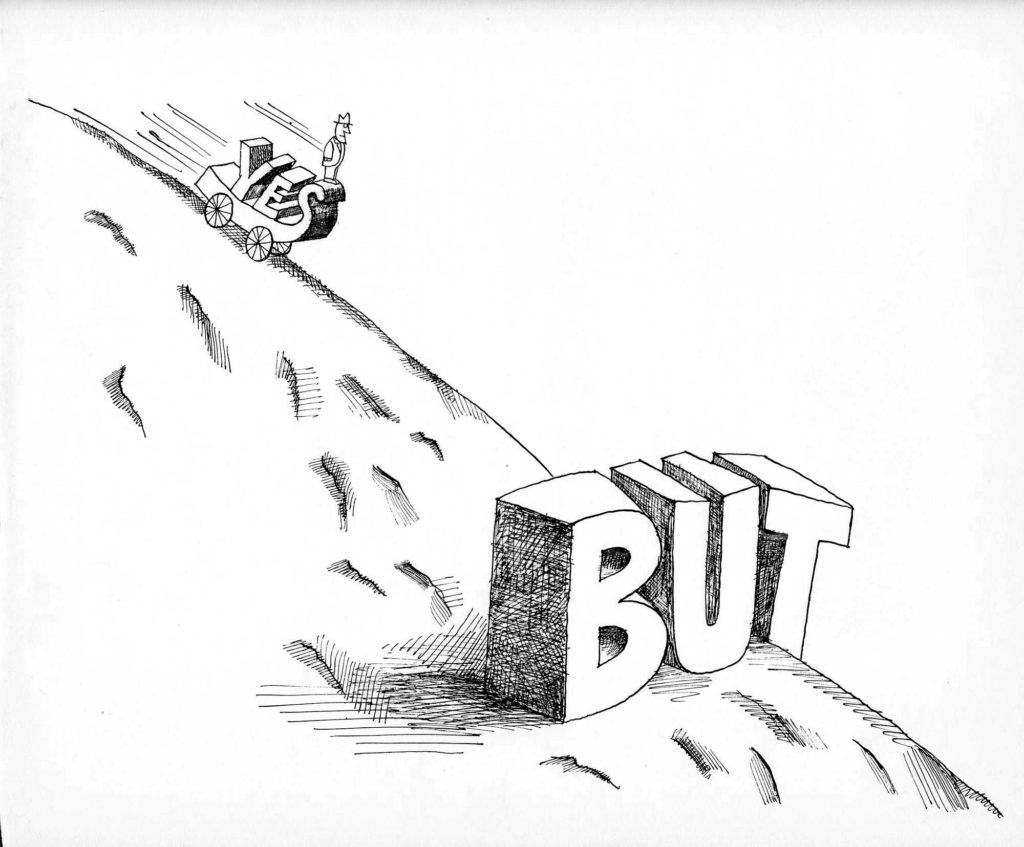

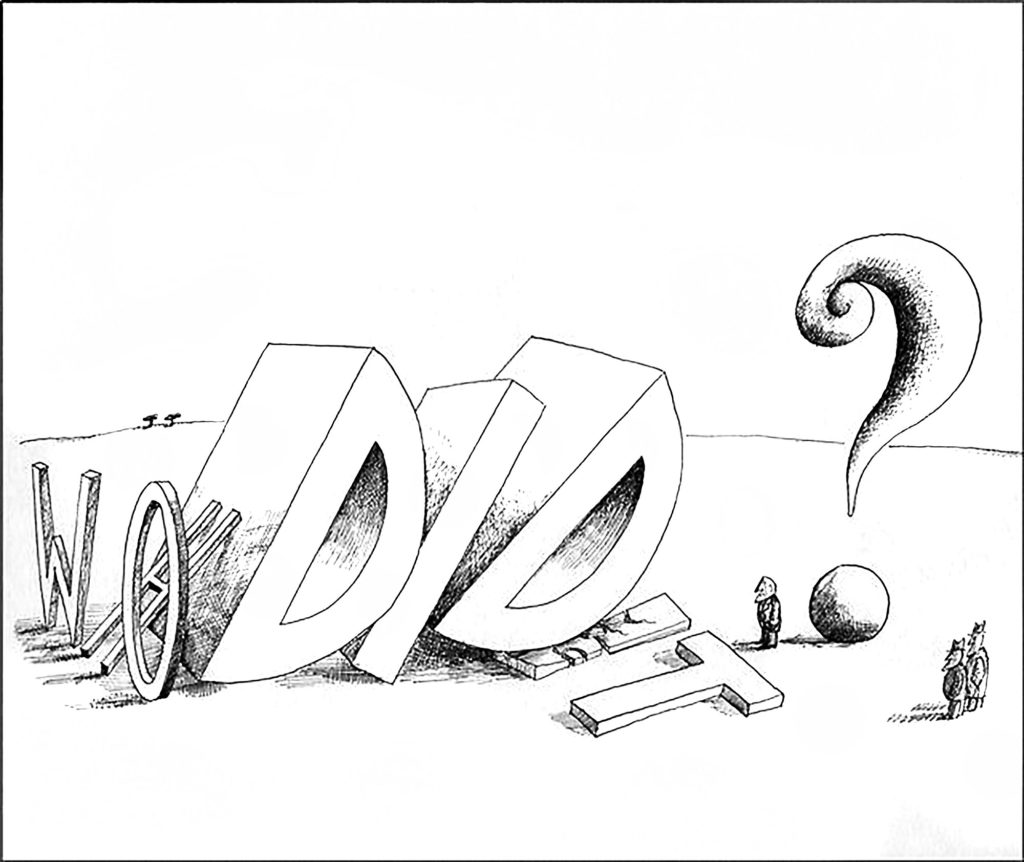

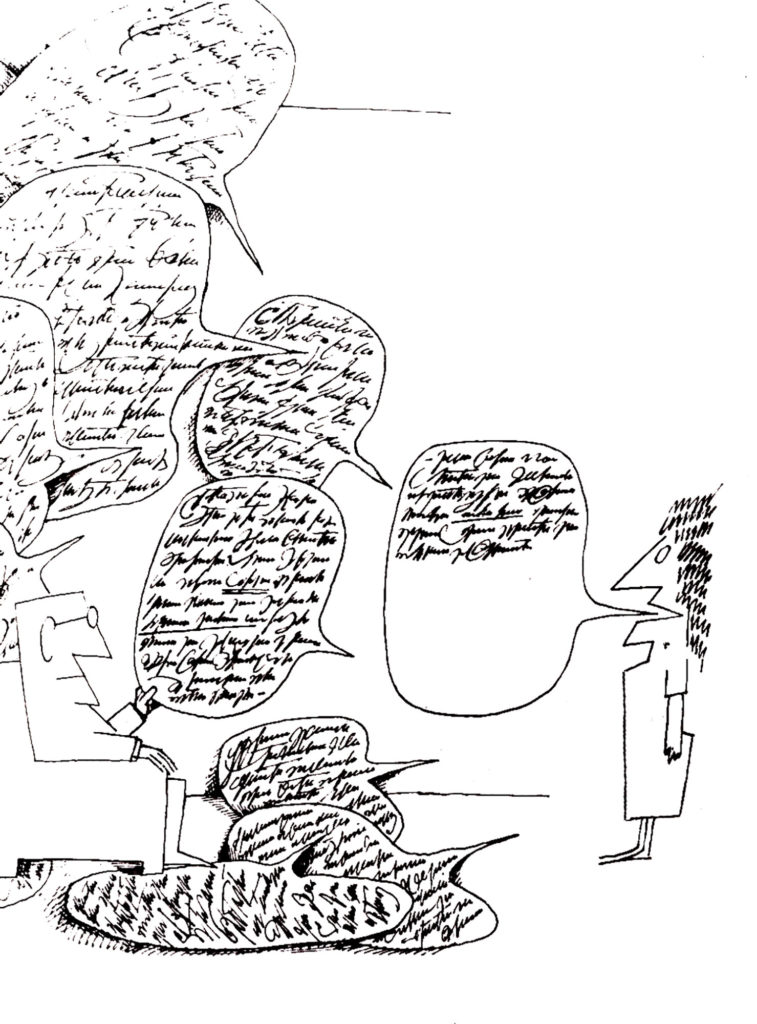

The following cartoon by Saul Steinberg not only sums up the basic premise of the idea of rules for reading and perceiving space, but examples it with humor on itself. There are all sorts of mark-making “rules” for artists to learn in order to make a three-dimensional illusion of space out of a flat two-dimensional piece of paper. Common depth cues used to render three-dimensional relationships include such things as perspective, overlap of shapes to establish their position in space, resolution of far and close detail, placement of objects higher on the picture plane to denote being further back in space, bigger shapes being closer, smaller shapes being further away, words inside a circle (with a point coming out of the circle) meaning something is spoken, the same words circled (with a series of descending circles) meaning it is a thought, color theory (including such concepts as advancing and receding relationships of color temperature), atmospheric rules of value and contrast, shadows and on and on… marks on a flat paper being visually “read” as space, audio sound or even thought.

In the image below, the inspector in Steinberg’s drawing is inspecting everything to make sure all the rules are executed correctly in order for us to read space correctly. With that as a premise, Saul Steinberg proceeds to break all the inspector’s rules and have great fun in the process. Steinberg created many cartoons for the New Yorker and its savvy audience. One maxim that does not go without saying, is that one must first have a masterful understanding of the “rules” before one can break them successfully.

Enjoy this run through of a few select samples of Steinberg’s tongue-in-cheek media humor.

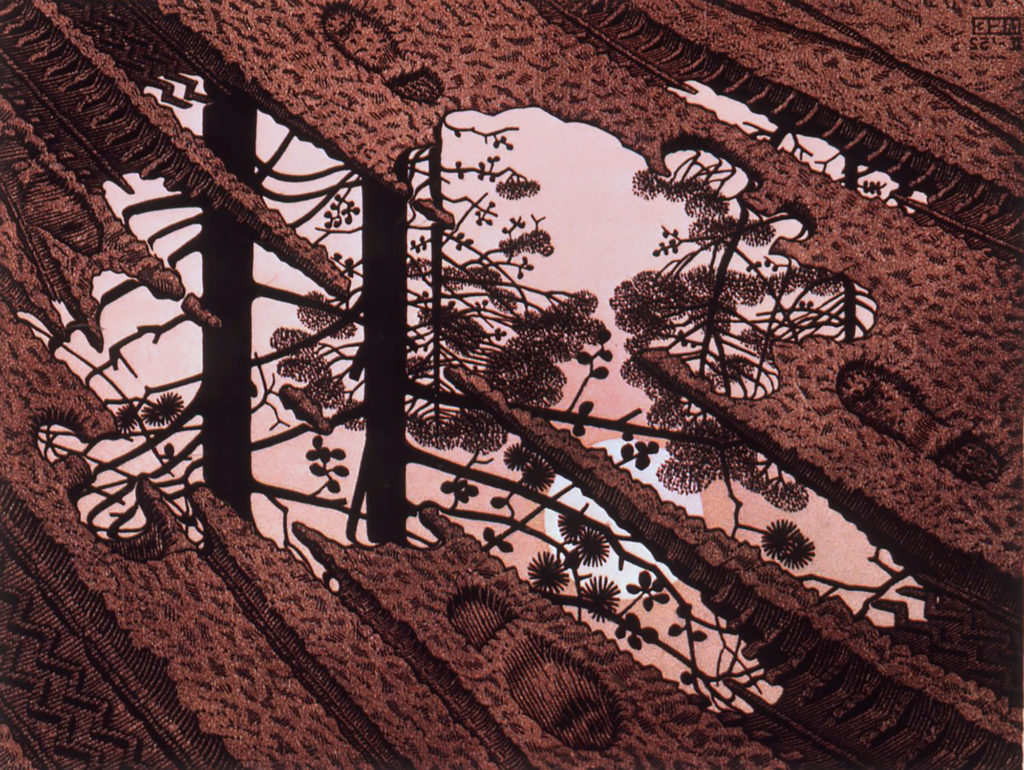

The funniest images are when we knowingly relate things that are totally unrelated or when we misread space in impossible ways. The most well-known master of the impossible space is M.C. Escher.

Wayne Thiebaud plays with impossible spaces that seem possible with his pictorial constructivist paintings depicting the streets of San Francisco.

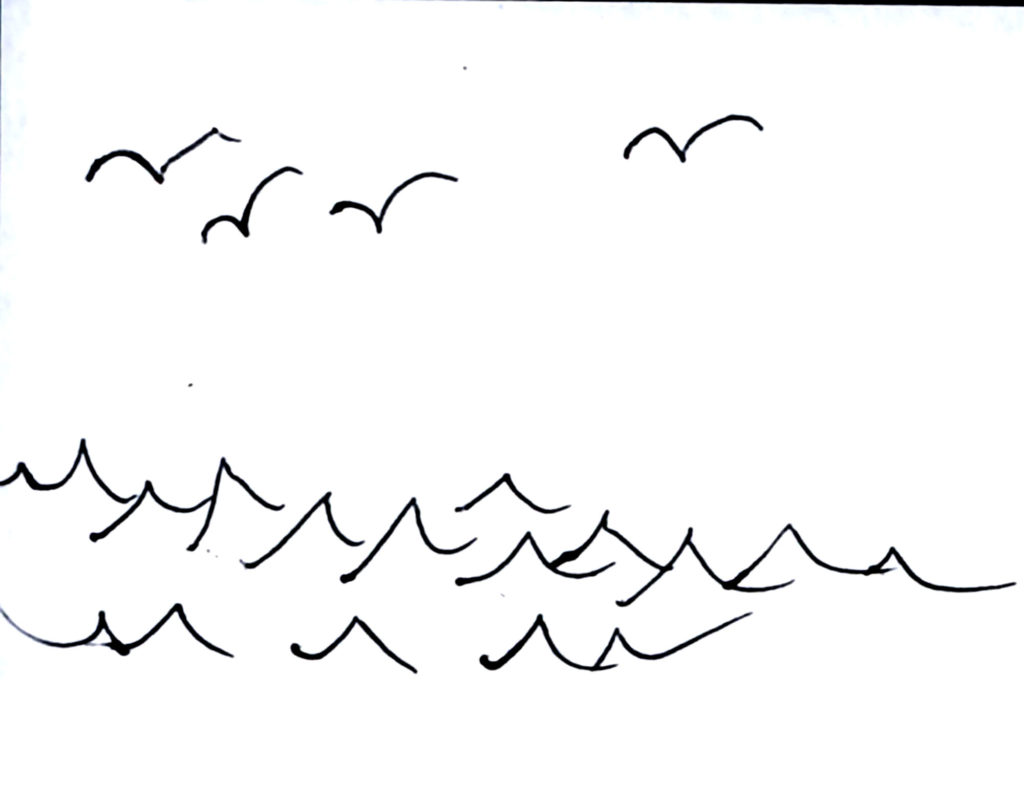

To read an image effectively, we must first learn the symbolic meanings of the marks we are looking at. One Sunday morning, I was having a cup of coffee at a friend’s house in the days when everyone got a Sunday newspaper with the Sunday comic section. It was a very relaxed morning… when all of a sudden his young son came running up to us crying and screaming because there was “a picture of a man killing birds”. The man was supposedly jumping up and down on them, laughing. We asked him to calm down and show us the picture. When we first looked at it, we couldn’t figure out what he was talking about. Then the light bulb clicked on. The child had learned to “read” what a bird looked like. The symbol for a bird was two curved lines, the point where the two lines met pointed down. When it is in the upper area of a picture, the bird is flying. He had not learned the symbol for a wave of water yet, which is the same graphic, only upside down and positioned in the lower portion of the picture plane. The man was jumping up and down having fun splashing in the water to us, but to the child, who only knew “bird”, he saw birds that were dead because they were upside down on the ground with a man jumping on them. So we sat him down and taught him the “vocabulary word” for a wave of water – and everything was alright. The “inspector” would have been very pleased with us.

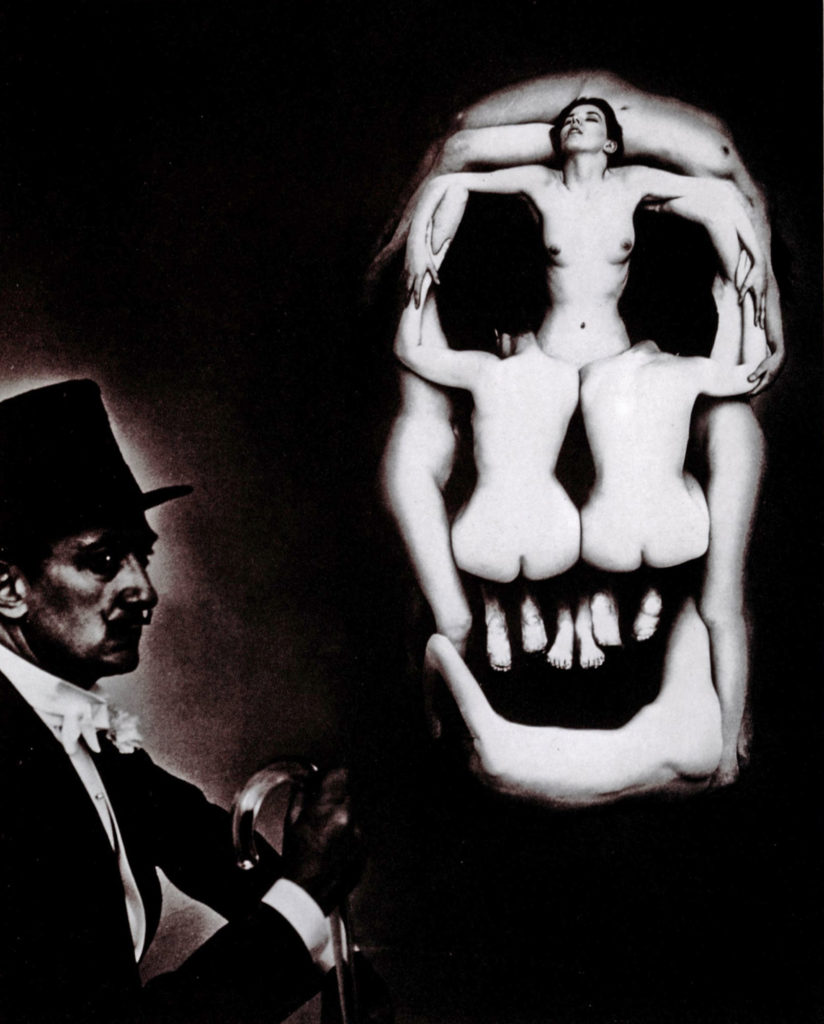

Like the child reading the same mark in different ways, the same marks that are used in the following drawings can be read in very different ways depending on how you choose to look at them.

The following are a few images that illustrate some basics about reading images as outlined in Gestalt psychology. These Gestalt rules of perception are used as the means to achieve what Gestalt psychology calls the Law of Pragnanz – the human understanding we have of our world.

We will always strive to understand our universe; we are confused when contradictions occur and we will make every effort to resolve what doesn’t make sense in order to reach an understanding. This is so strong an instinct that even when we know something to be true, if our illusion is coherent, we tend to go with the illusion. For example, the conflict between perceiving and knowing can be illustrated with a ventriloquist. Why do we associate the sound with the puppet rather than the real speaker? Even if we know it cannot be. The artist is always exploiting these kinds of perceptual signals.

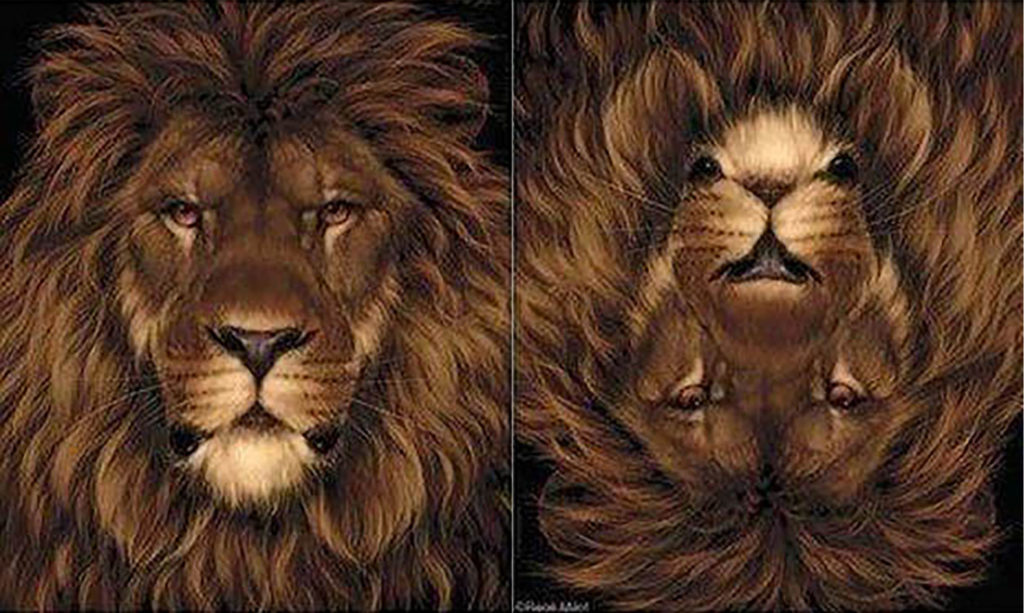

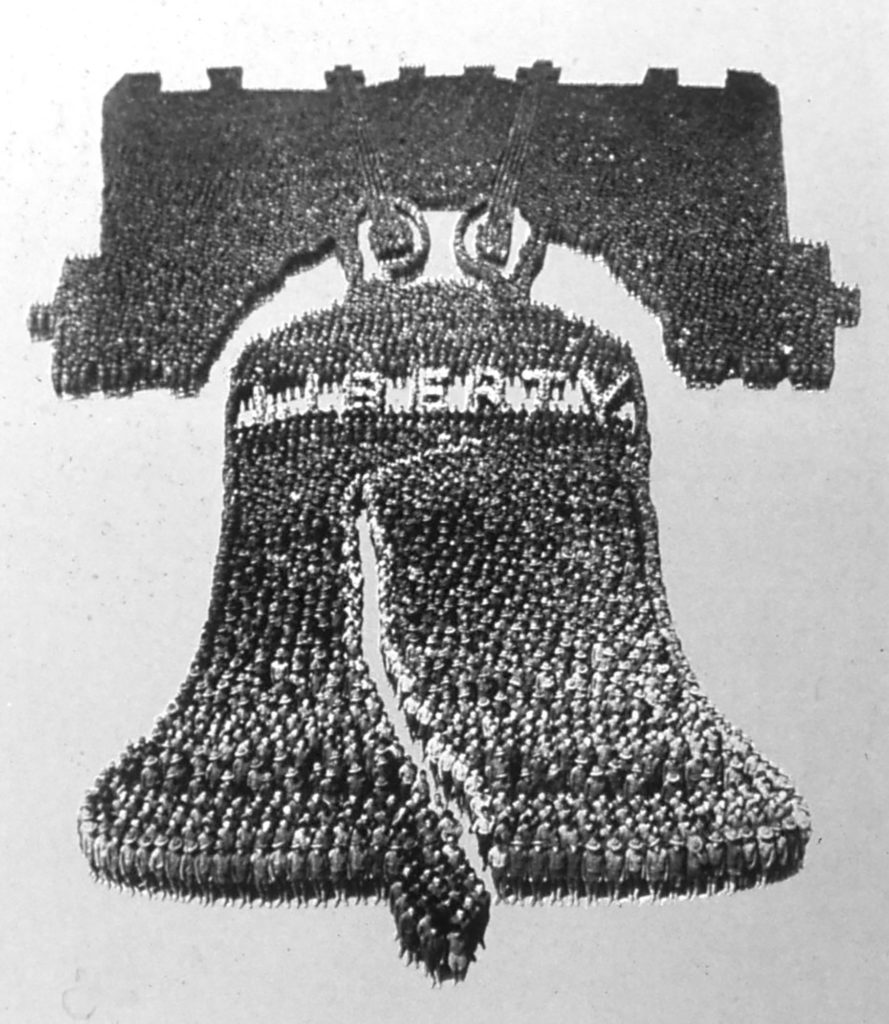

These images illustrate the basic idea of a Gestalt (the whole is not the sum of its parts) as when we see a face in a cloud, or a boiling mud pool. The following images illustrate the premise of a Gestalt, when the the whole that we see has nothing to do with the parts that make it up. Our instinct to relate the parts in some fashion in order to make some sense of it is so strong that what we see is in contradiction to and stronger than what we know to be true.

Another Gestalt rule of perception:

Reality is organized to the simplest form possible. For example, we see the image below as a series of overlapping circles rather than as many much more complicated shapes.

In the following image, aside from the formal aesthetics and a play on the Abstract Expressionist Painting movement, the Gestalt is what makes it for me – the humorous absurdity by which the viewer “reads” just three little, out of context dots amongst this complex and abstract mess as a “Peep”. Quite a stretch, but there you have it, a little humor at play with some perceptual stretching behind it.

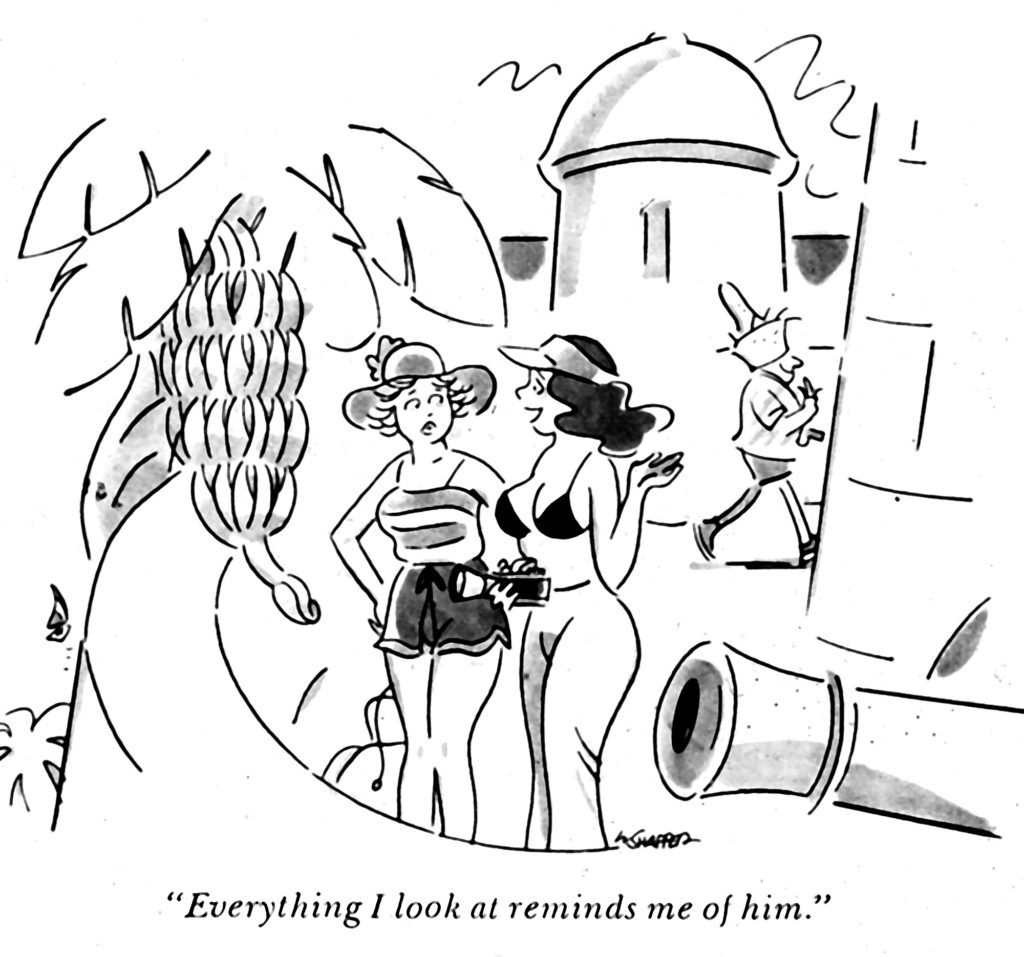

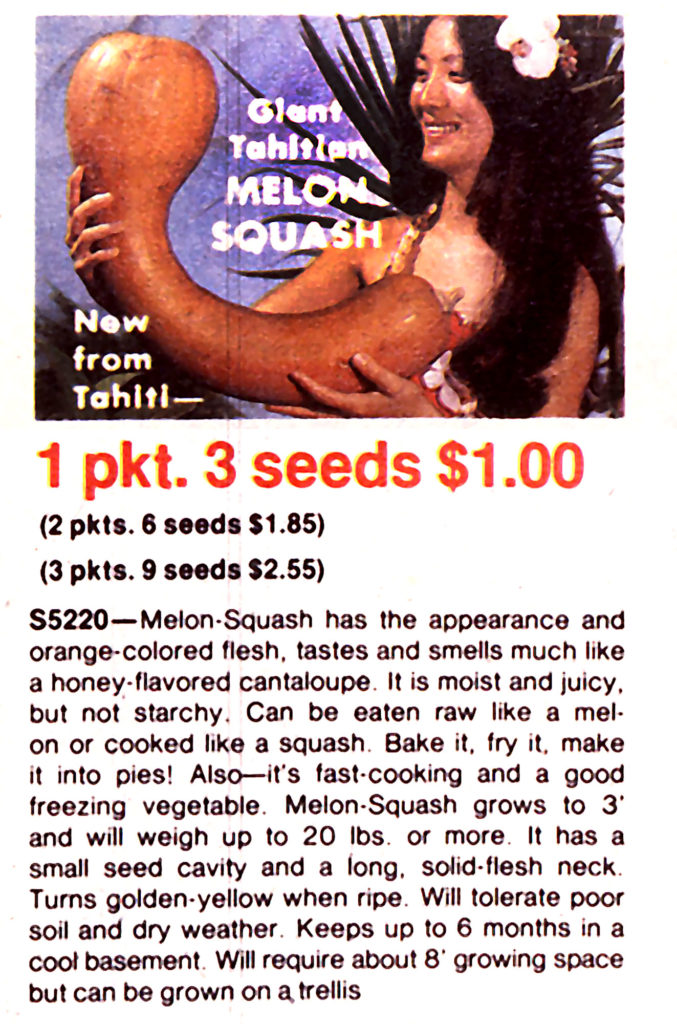

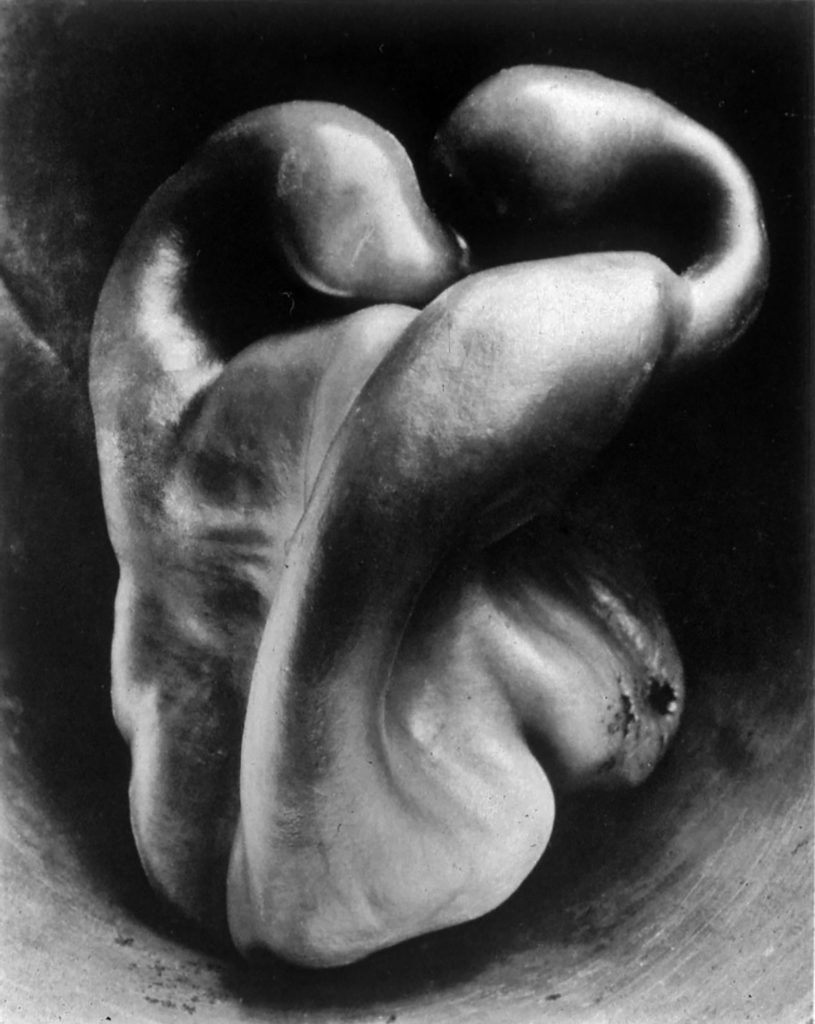

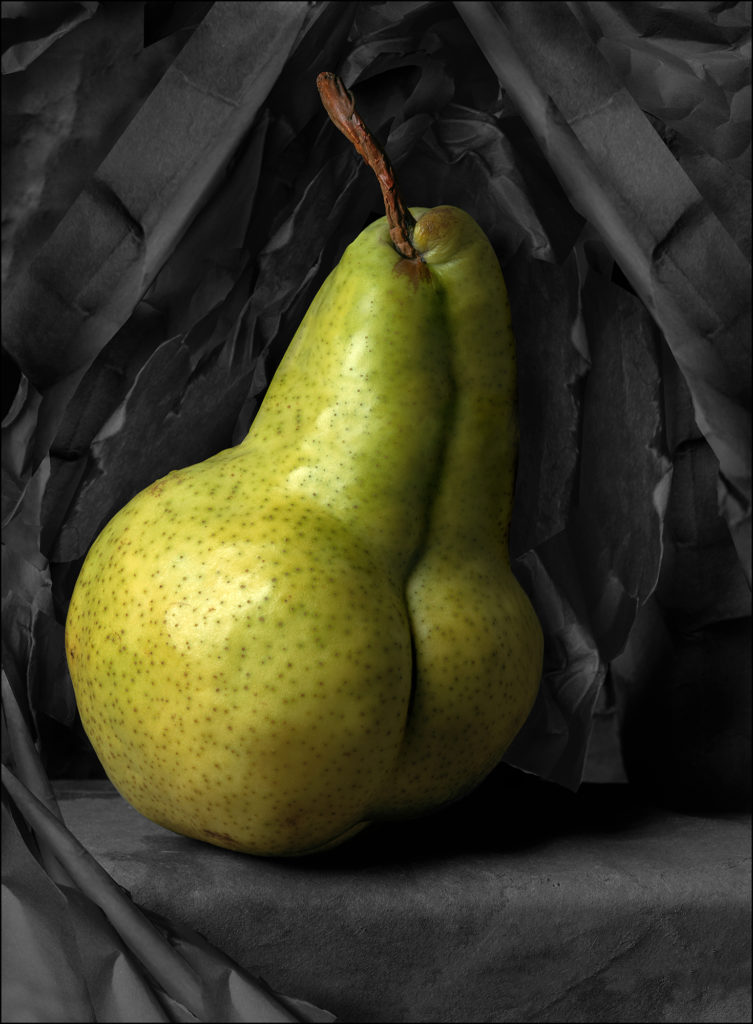

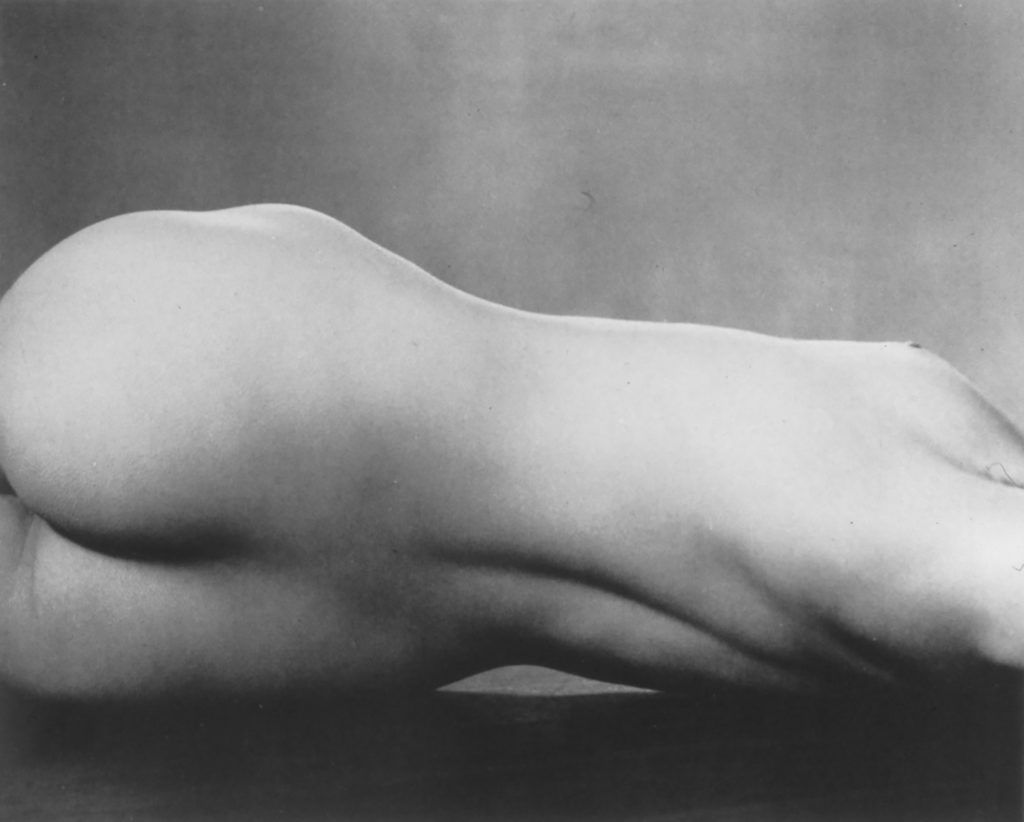

One of the most common Gestalt Laws of visual perception used in art is the “law of similarity”. It goes that whenever we see different things as being similar we will tend to relate them. A formal visual element can be similar in form, shape, color, texture, pattern, and so forth. The parody is a sub-category of similarity where one image is similar to another well-known image, icon or archetype. Similarity is often used in advertising to relate a product to something otherwise unrelated. Sexual references are commonly used to sell absolutely anything, because sex sells.

The following are a variety of examples using the visual law of “similarity” to create relationships. Also included are some examples from magazine advertising that I have collected over the years.

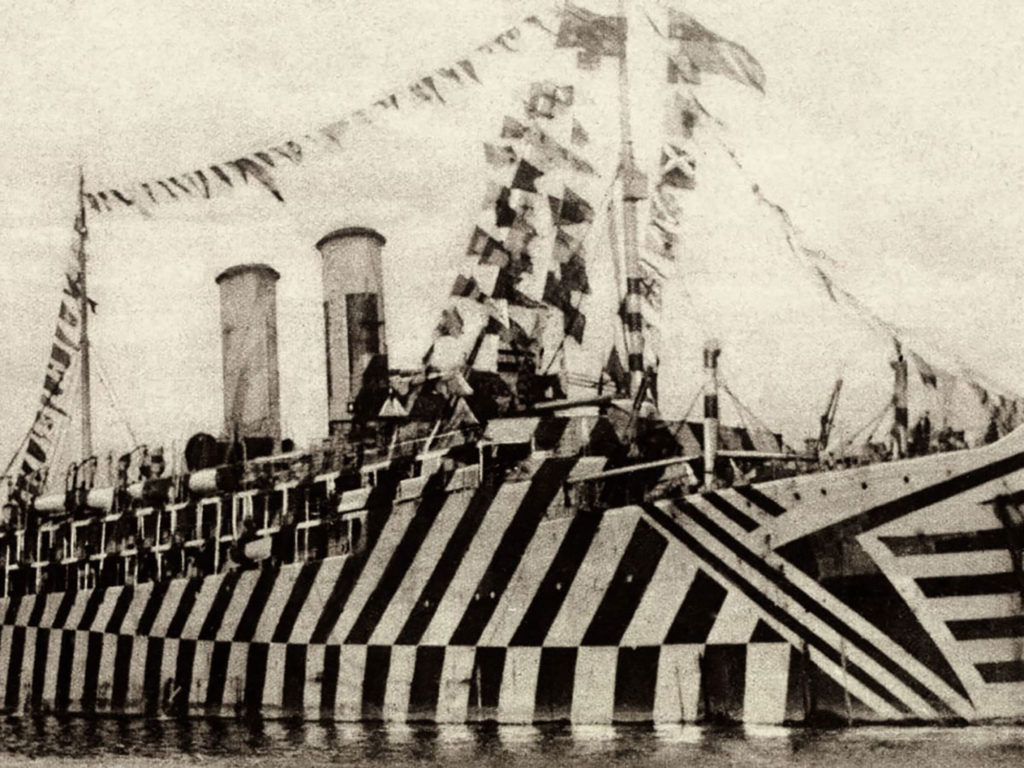

Camouflage is a special Gestalt principle involving “Similarity”. Camouflage depends on clouding the perception of an object’s relationship to its background with a similarity of attributes such as shape, color, texture and pattern.

Here is a Peep image in which “similarity” is used as camouflage. It is in the form of the ginger where one can find a hidden Peep within this aesthetic arrangement of ginger. Without the title as a key, it is unlikely that the camouflaged apparition would appear in this calculated balance of form, color and texture. But once you see it, you cannot choose to not see it as that is how understanding and perception work.

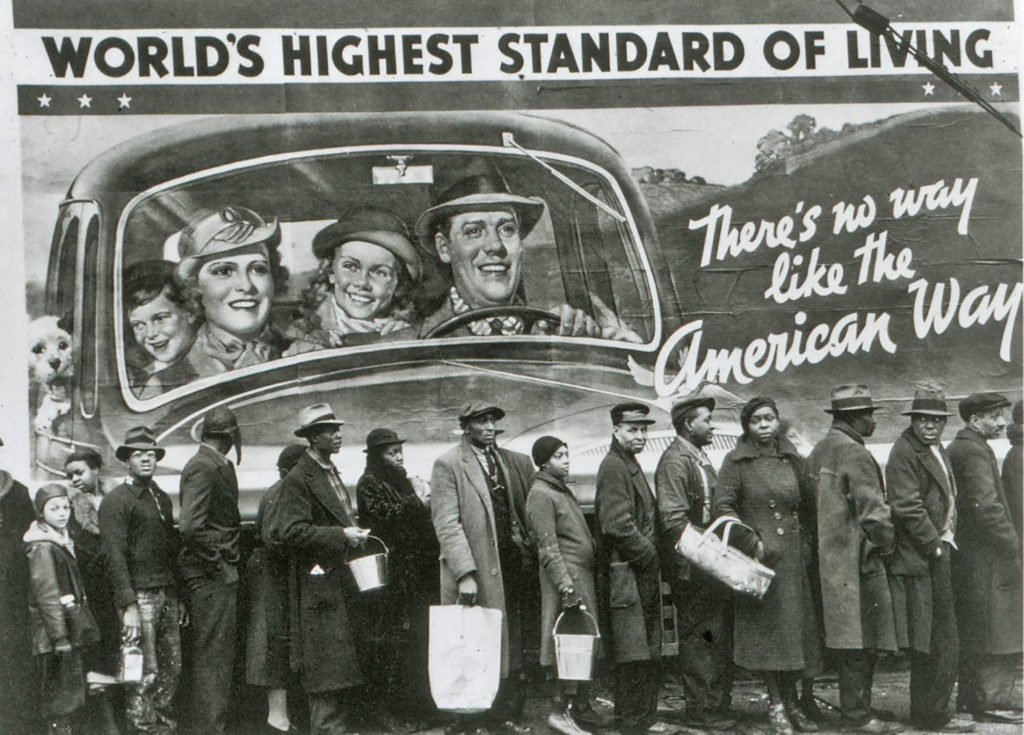

Another of the most commonly used Gestalt laws of perception is the Gestalt law of juxtaposition. In this perceptual law, we will tend to relate anything that is in close enough proximity to anything else. The Gestalt law of relating disparate elements through juxtaposition is used a lot in art. In this case, two unrelated ideas add up to form a new idea, often with a humorous edge. Frequently, juxtaposition is used in conjunction with the law of “similarity’ to force us in an even stronger way to relate unrelated things that would otherwise not be seen as related. These forced relationships are often used to create feelings of tension or harmony along with visual satire.

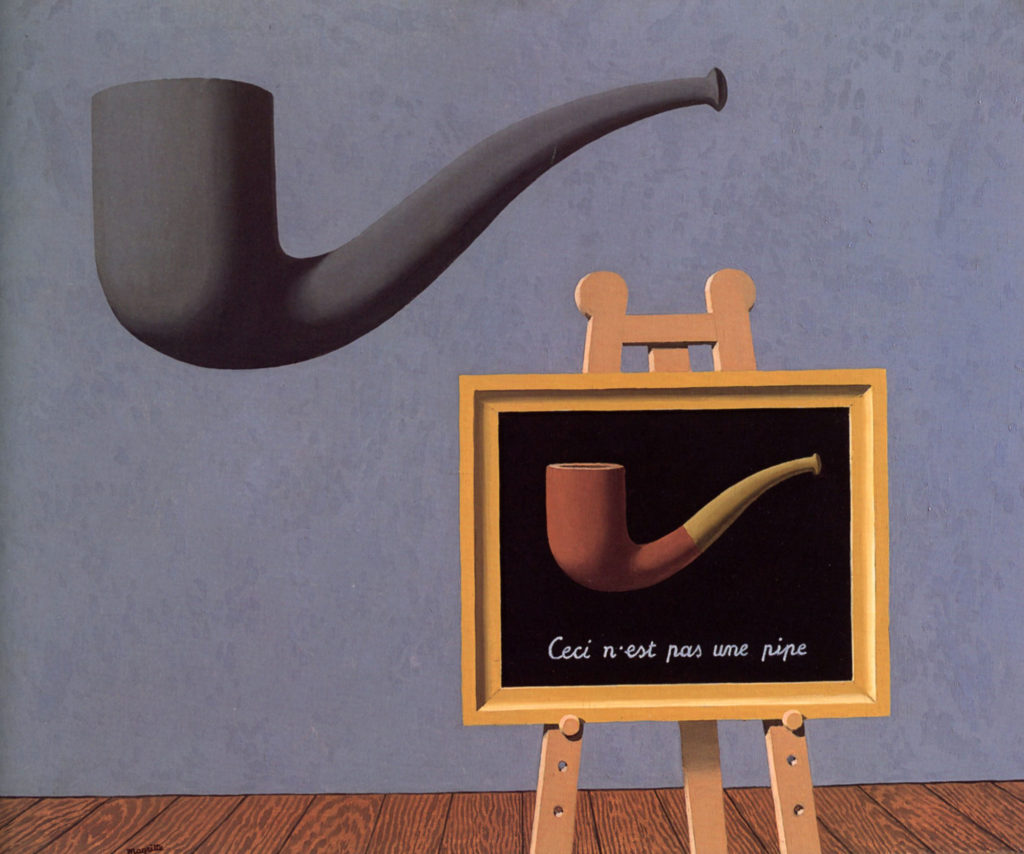

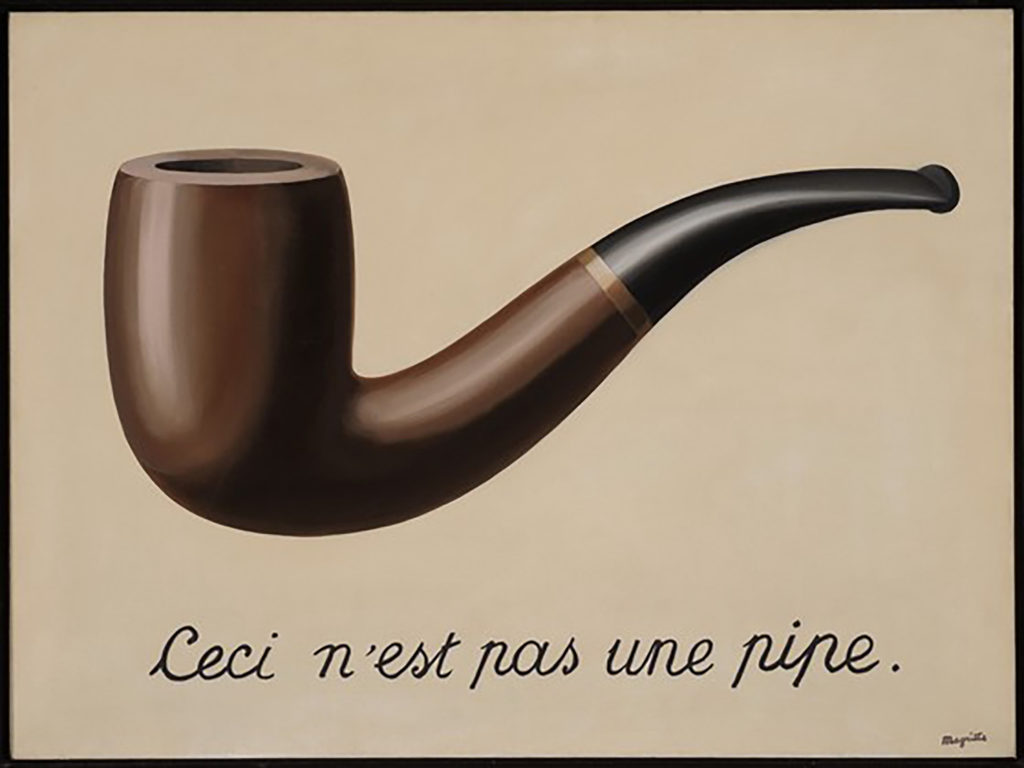

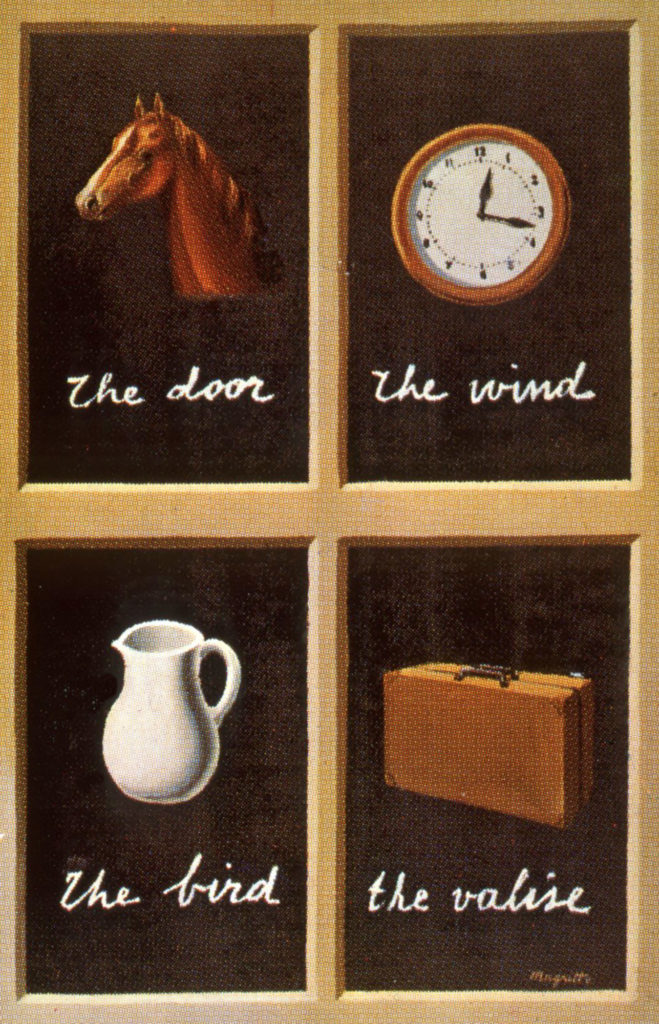

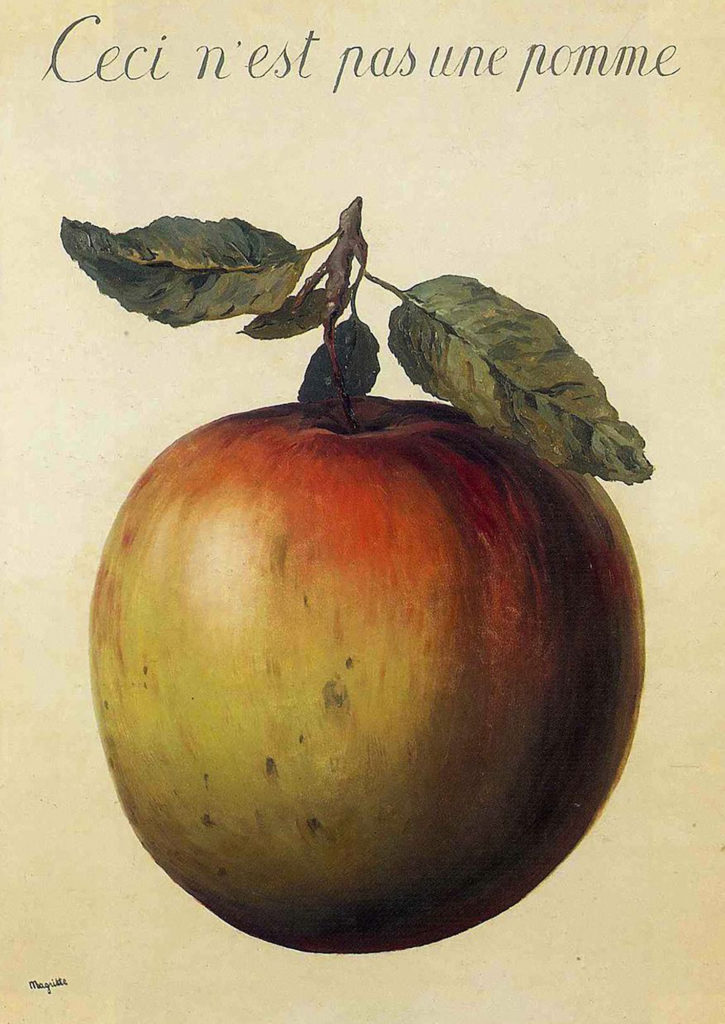

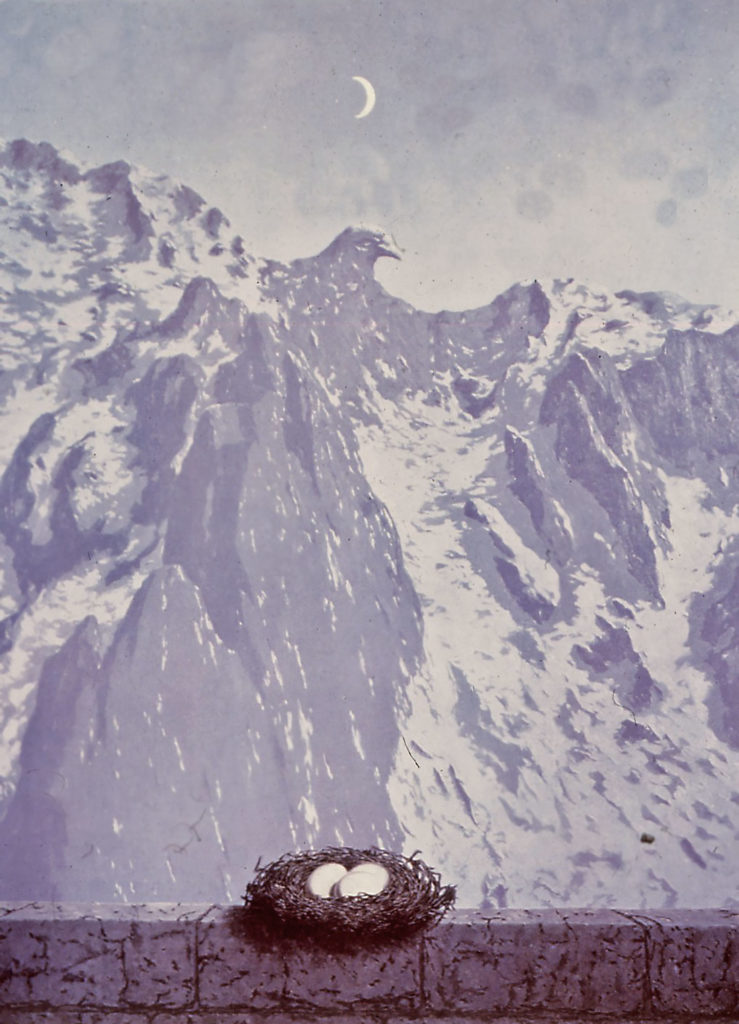

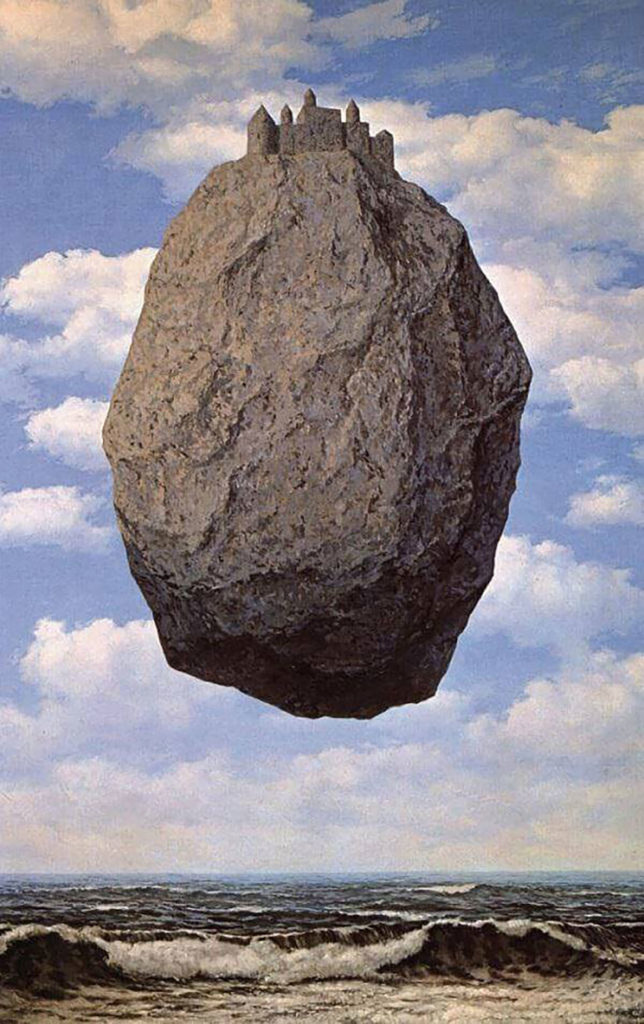

One of the greatest masters of relating disparate realities through Gestalt principles of perception is the painter René Magritte. In his series This is not a…, he points out that things are not what they seem and the problematic difference between a word and its counterpart. These works are commentary on the rules which Magritte breaks in his images, much as Steinberg used his style to comment on his own work in The Inspector. As with most surrealist artists, Magritte relies on these differential premises to undermine our assumptions about the nature of reality. There is existentially something troubling about it all 🙂 His 2016 retrospect in Paris was called The Treason of Images and indeed Steinberg’s inspector would have thought of Magritte’s work as treasonous.

Interesting trivia: Paul McCartney owns this Magritte painting. This enigmatic image inspired the Beatles to call their recording studio “Apple Corps” (note pun), using Magritte’s apple for their logo. Steve Jobs liked this iconic logo so much that he bought the Beatles rights to it and it evolved into what the world now knows today as “Apple”.

When the first permanent photograph was invented in the 1820’s, a sophisticated and well-developed system for depicting illusion had already been flourishing in painting and drawing for centuries. In the art world, this created a historically offensive-defensive environment towards photography due to the ease at which photography could depict realism. Regardless, the high illusion of a photograph is still constituted by marks on a flat surface. The process of making “marks” with light and light sensitive material is different from paint but the same rules of visual perception apply. If the inspector’s rules are not understood, poor photographic communication can result in some very humorous images. Fast forward to the advent of the digital age, where photo-humor is proliferated in the hands of anyone with a cell phone.

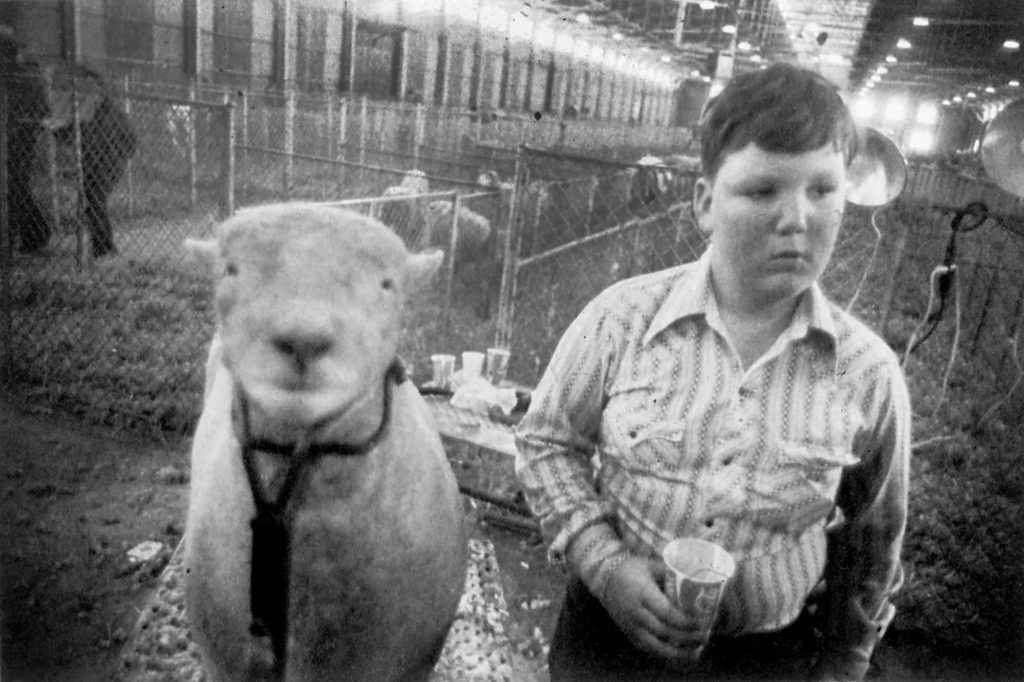

The perceptual and psychological interpretation of a photograph has always embodied an element of truth that sets it apart from other visual forms. Due to this assumption of honesty, photography has always been used to create, manipulate and shape truth to an end of blurring the edges of what is real. A photographic truth can be manipulated to levels of believable absurdity not possible in other visual media such as painting. A photograph is rarely neutral and usually reflects the photographer’s truth. The vast majority of photography is of serious content, commonly reflecting social issues or with the persistent attempt to document something. Social commentary is all the more powerful when it is coupled with artistic vision and whenever a human eye and brain is involved, it is likely that humor will creep into any photographer’s work in one image or another. A photograph always reflects a way of thinking and observing and can be a useful tool for making sense, or nonsense, of the world in which we live. A camera can even be a humorous device in itself as Andy Warhol demonstrated when he went to parties with no film in his camera and clicked away.

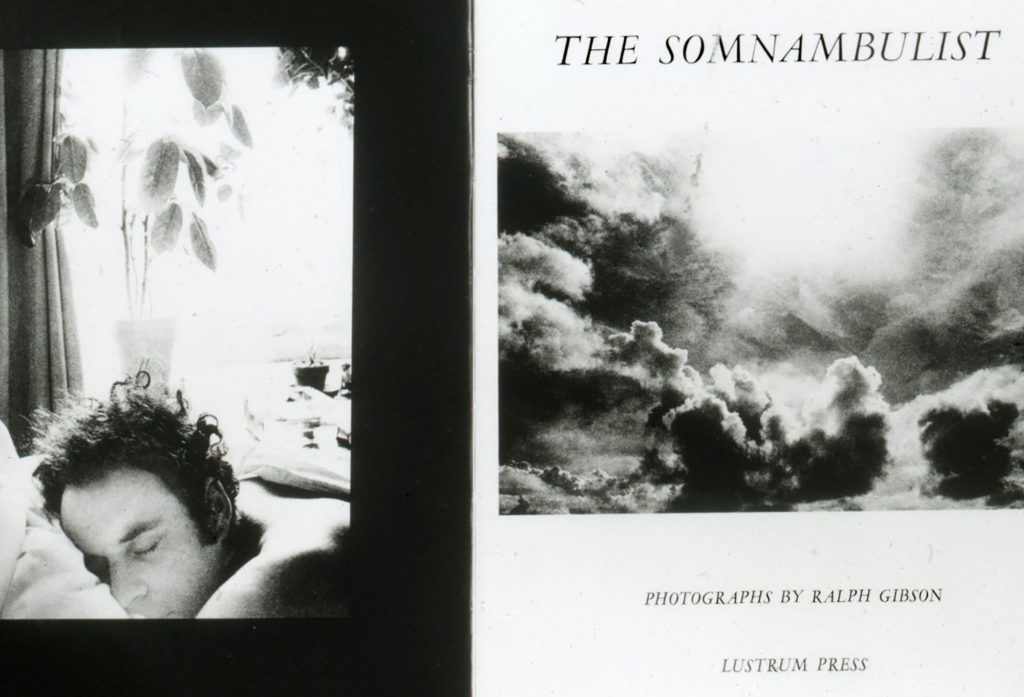

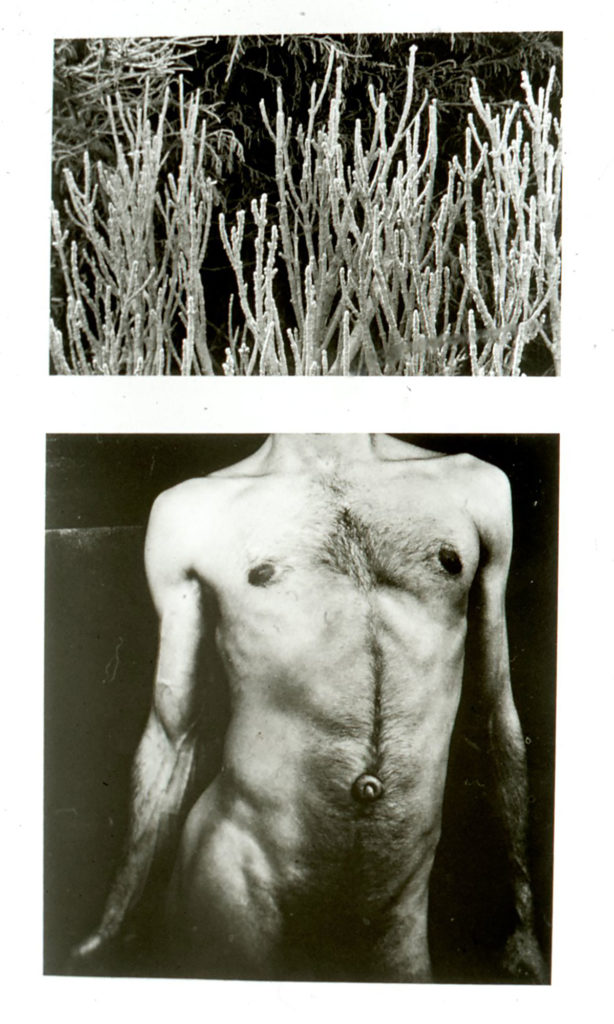

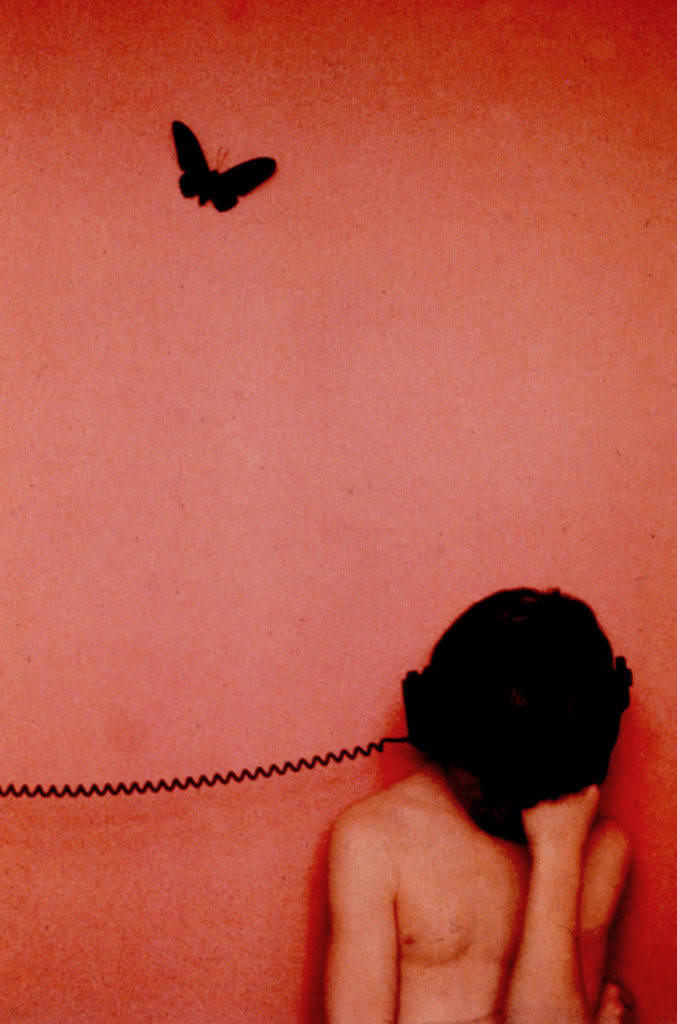

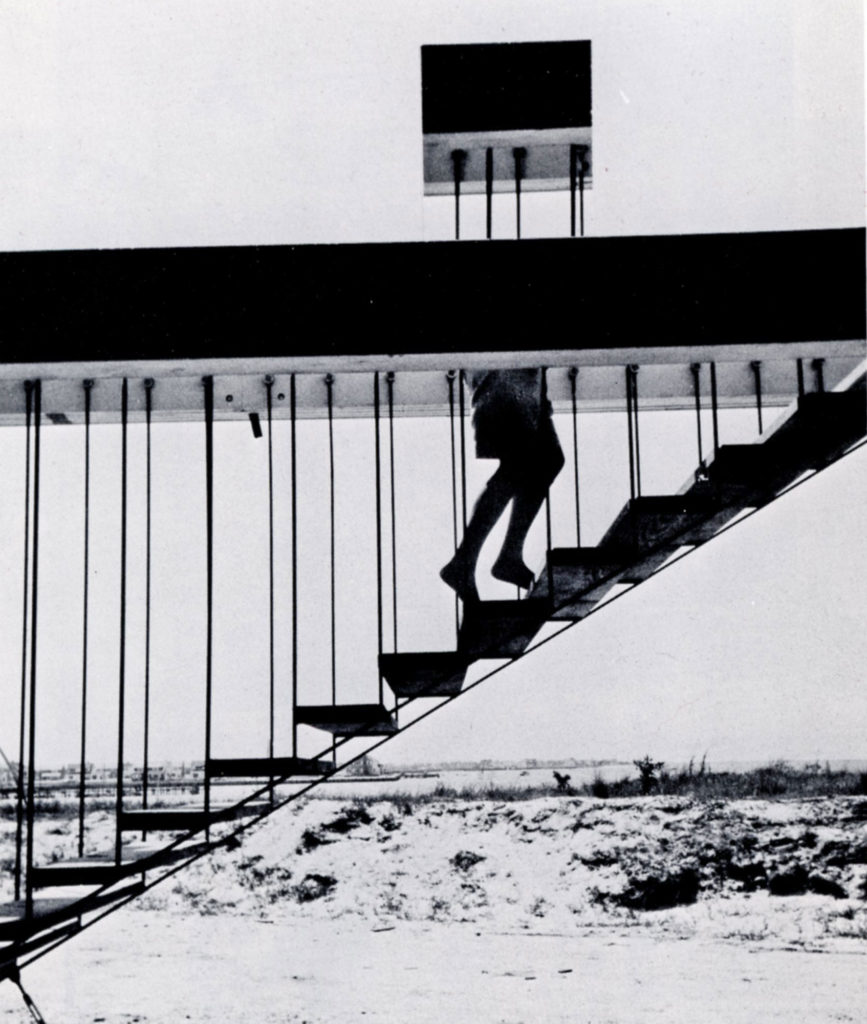

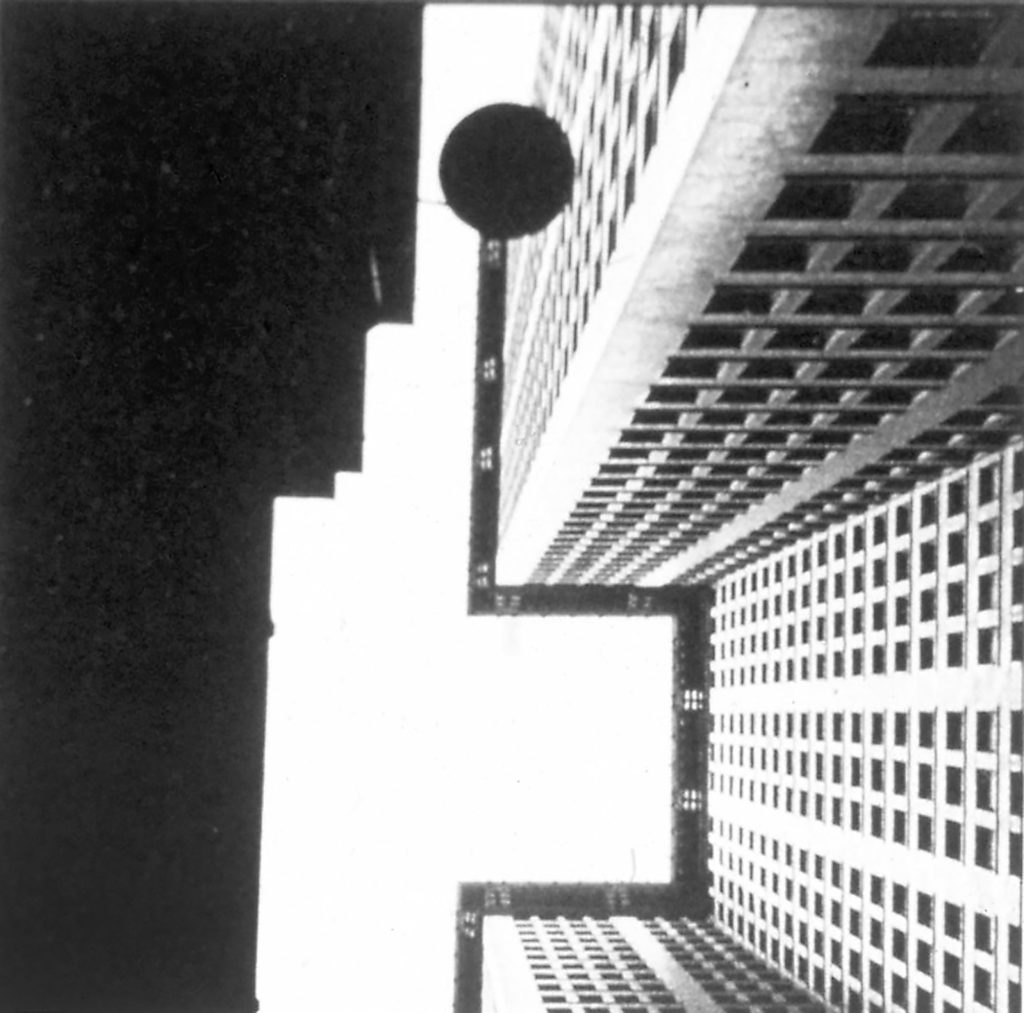

The nature of media is often an intriguing process of self-reflection in which the painting or photo questions itself. The viewer is caught in the trap. From the beginning, bending the inspector’s rules in photography was fertile ground for humor. The following are a few photographic examples of explorations that break the perceptual rules we use to read images, in my opinion, in some humorous and witty ways.

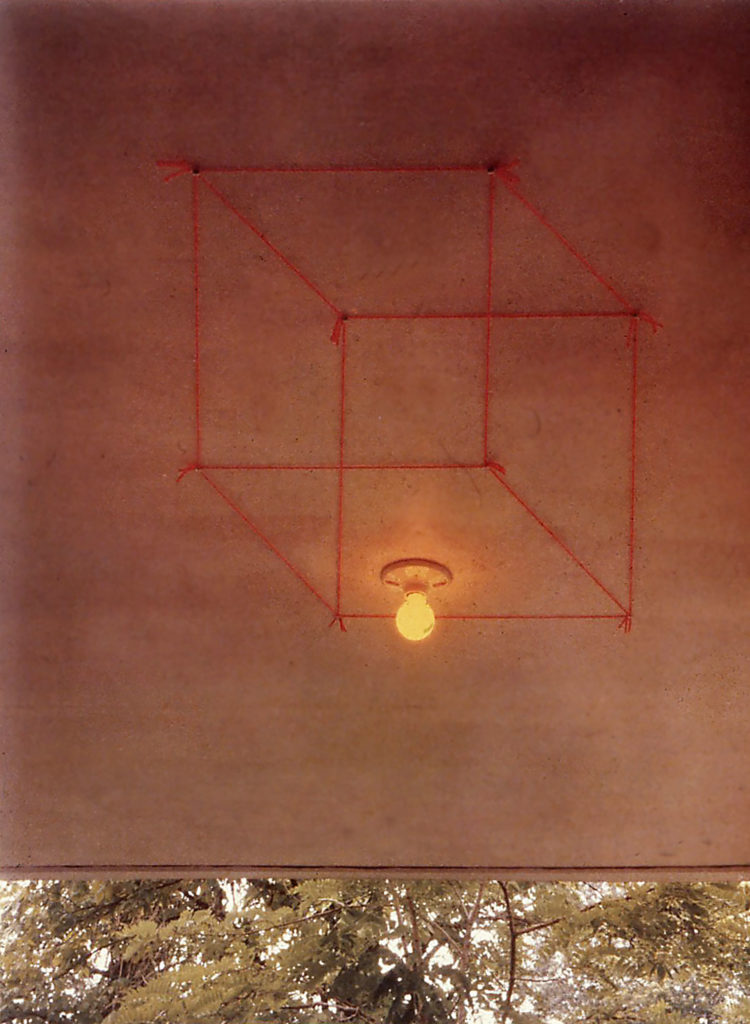

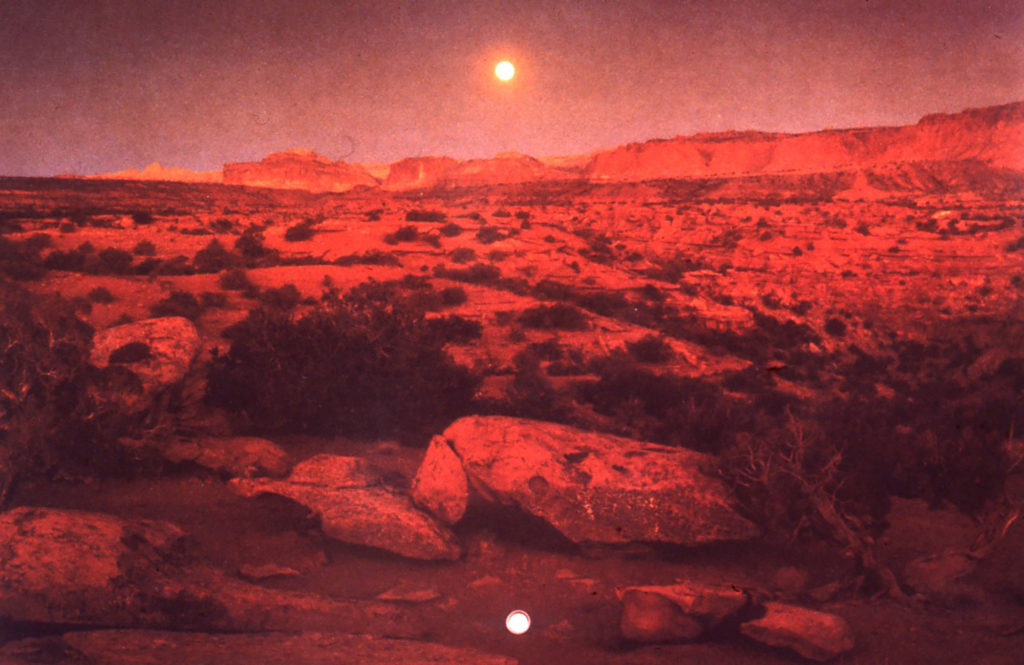

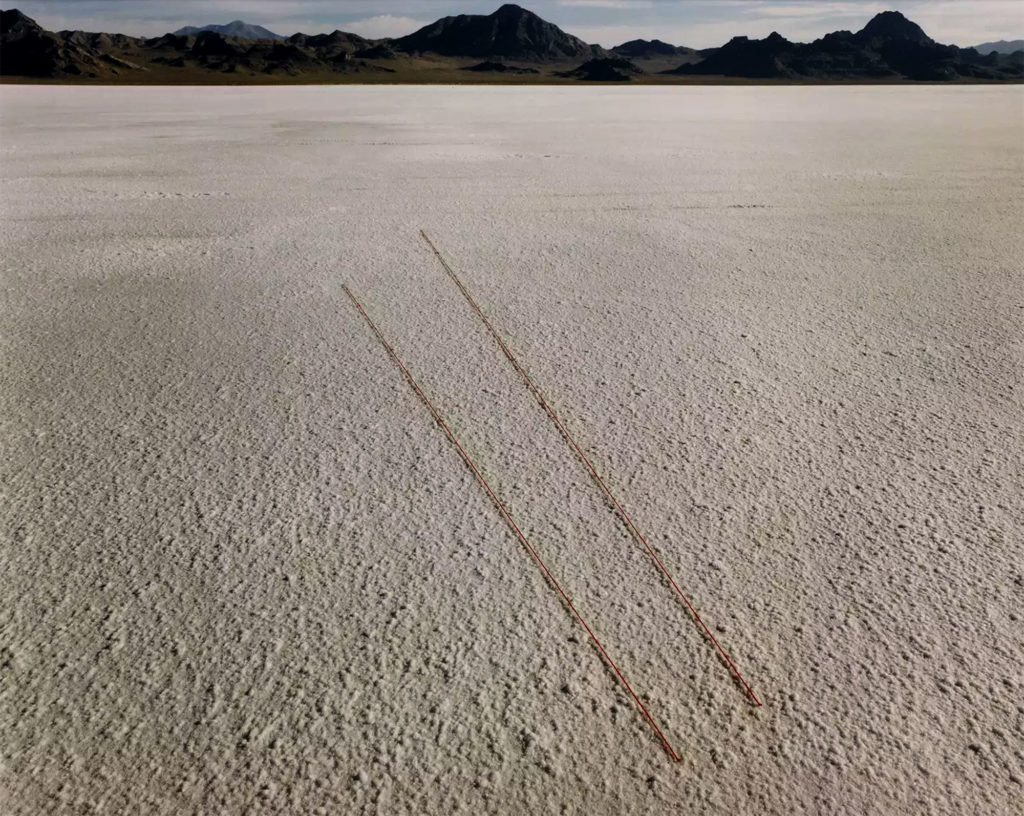

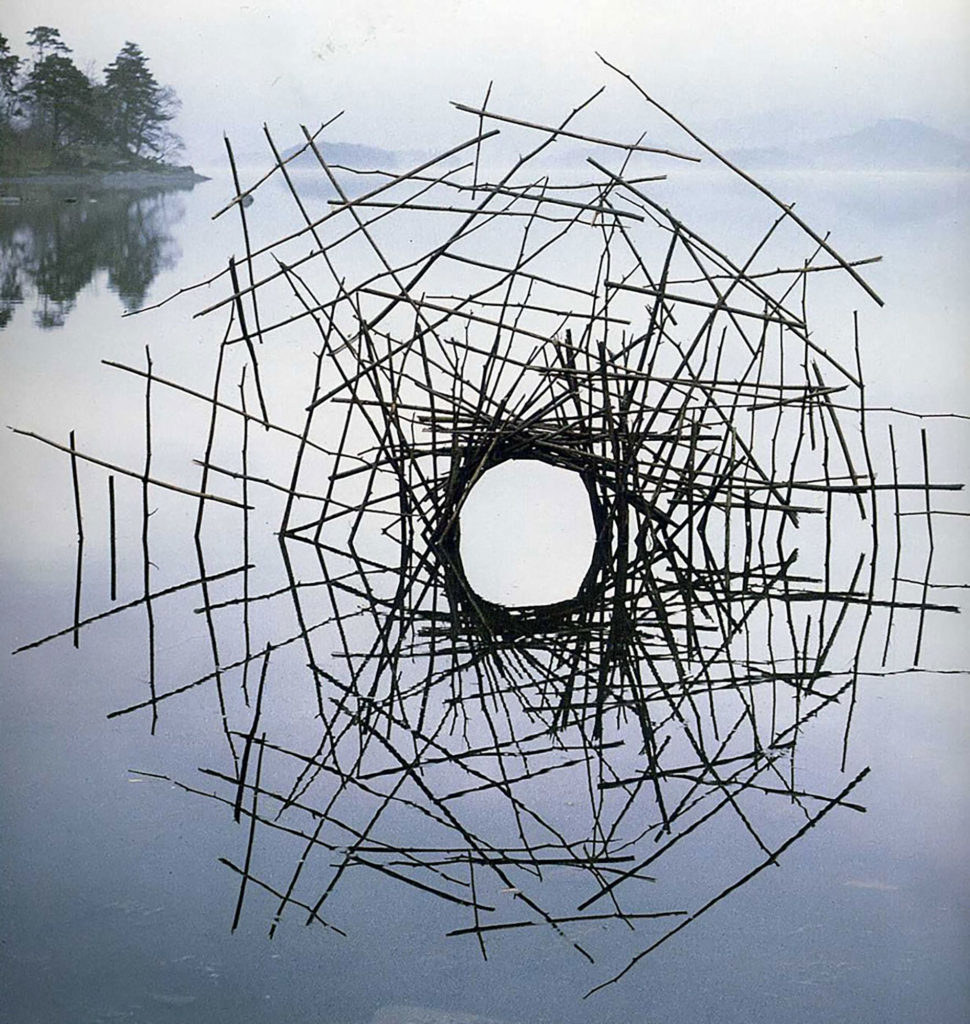

Andy Goldsworthy is a British artist who often uses the environment as his canvas to produce what is called Ephemeral Land Art or Environmental Art. Much of his work is of a temporal nature and photography is used to document the work and represent what was created in nature with nature.

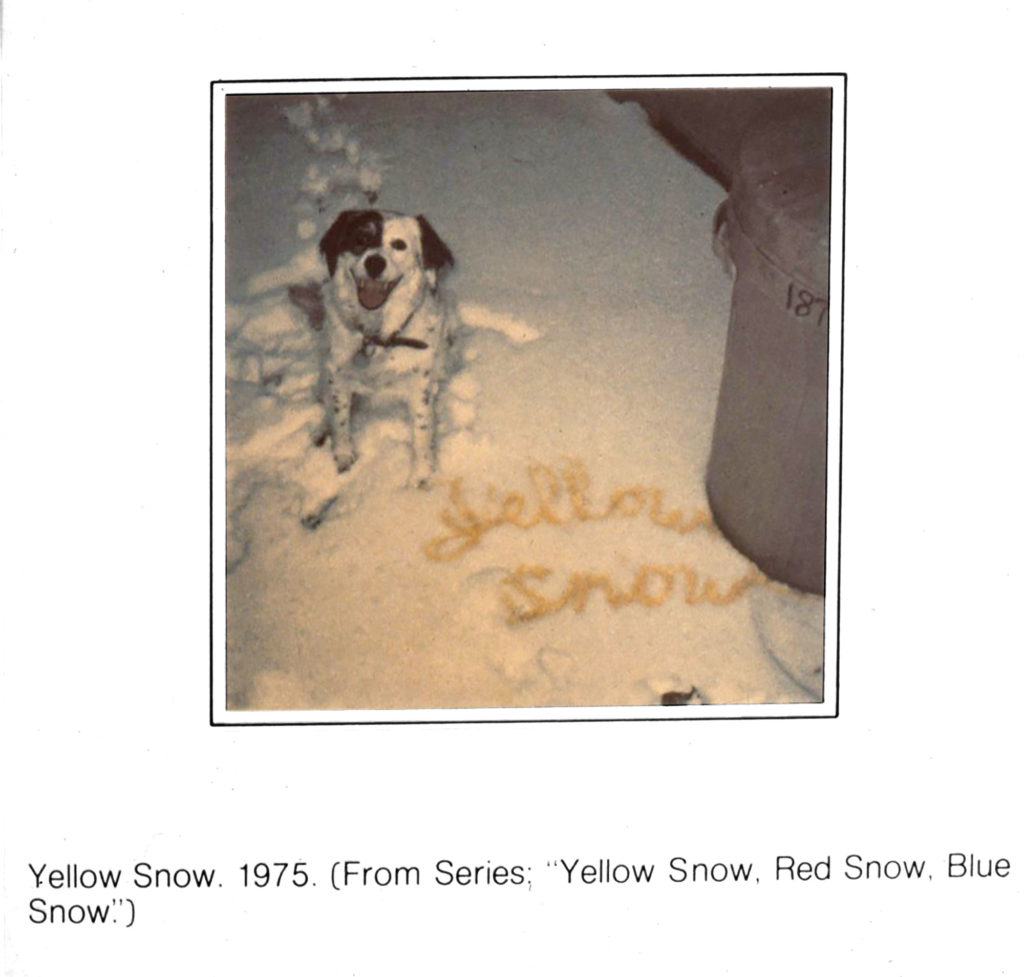

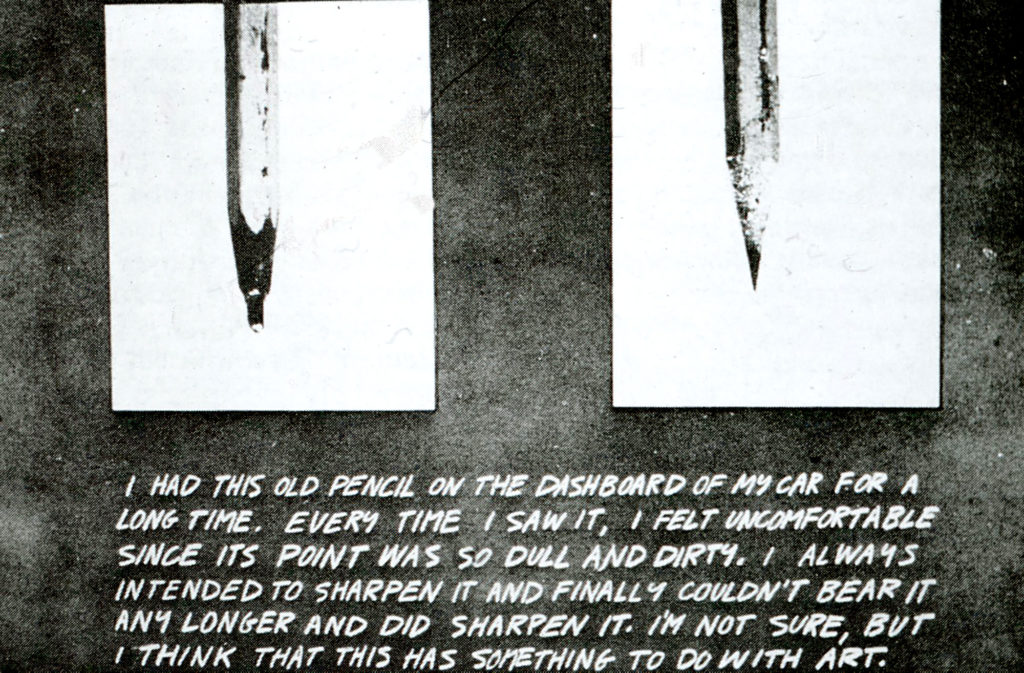

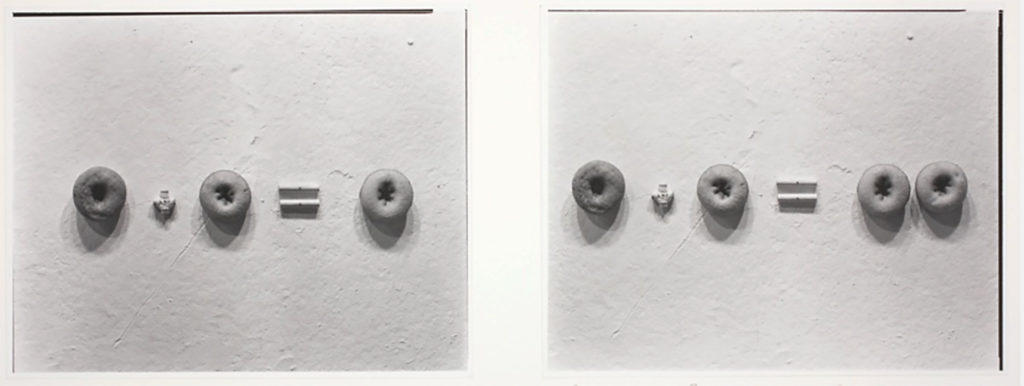

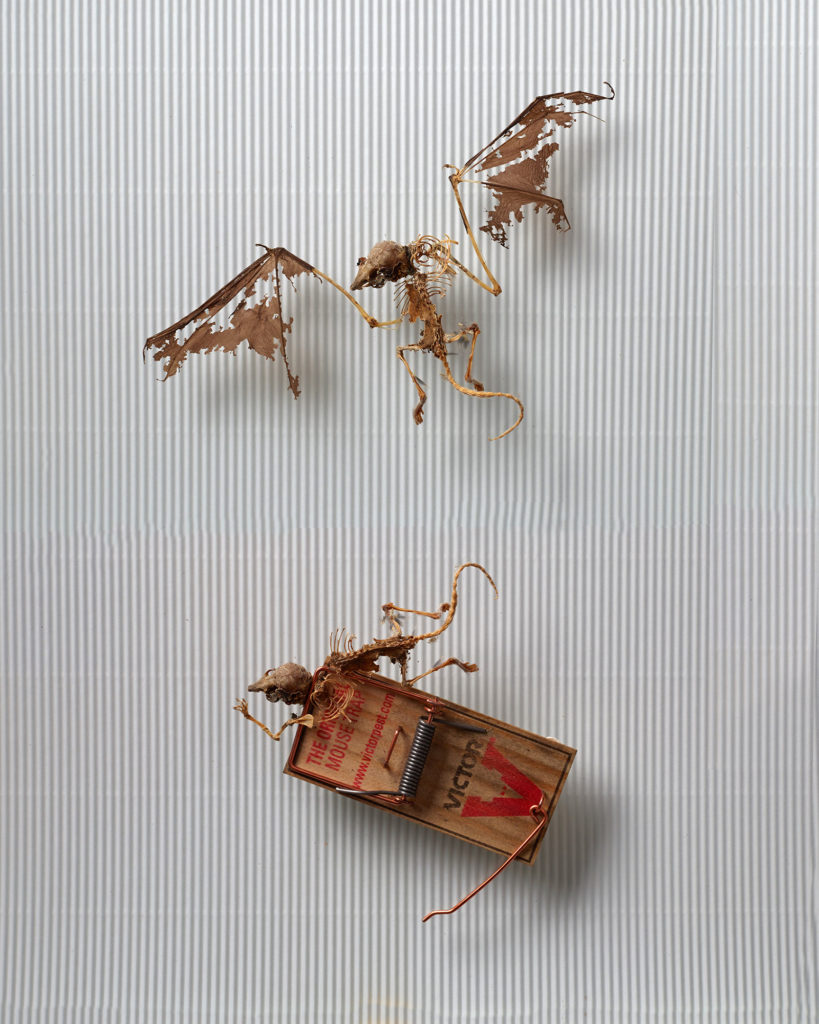

Conceptual Art can be a confusing genre but I just keep it simple and define it as when the idea is more important than the physical art object. It is commonly believed that Marcel Duchamp’s urinal, 1917, was the first conceptual piece of art. There is often humorous and absurd wit to conceptual art. Here are a couple examples.

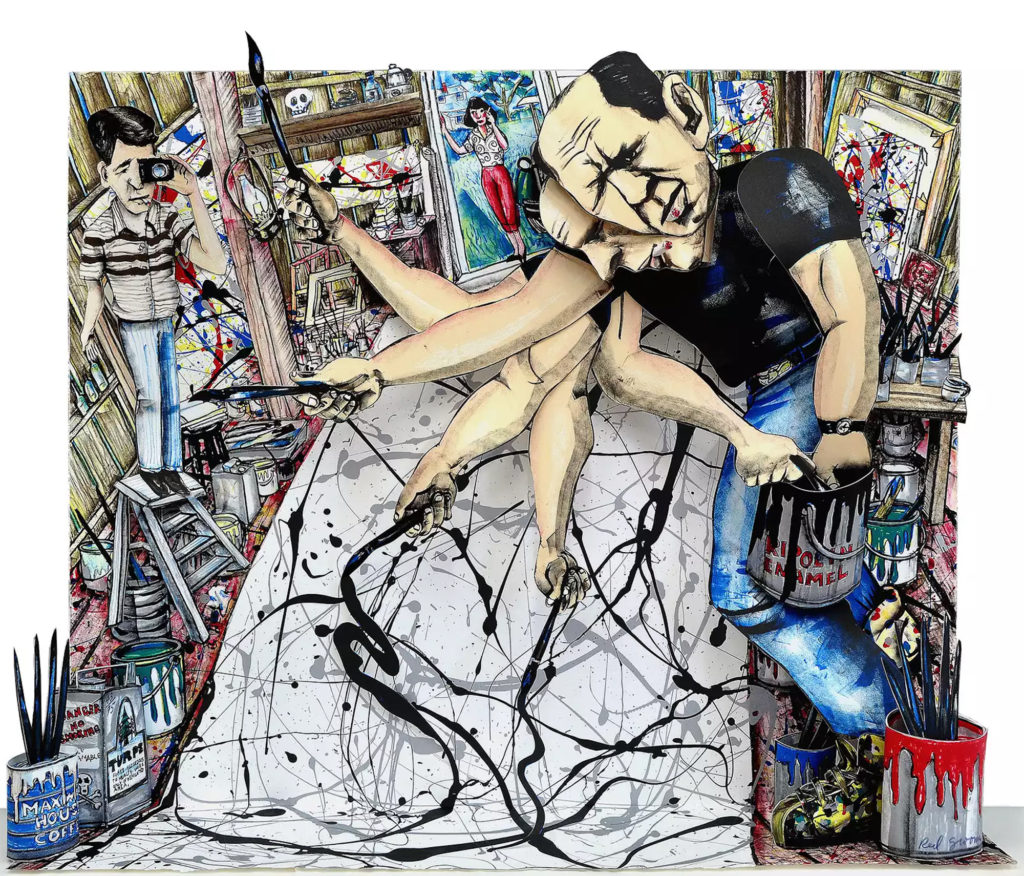

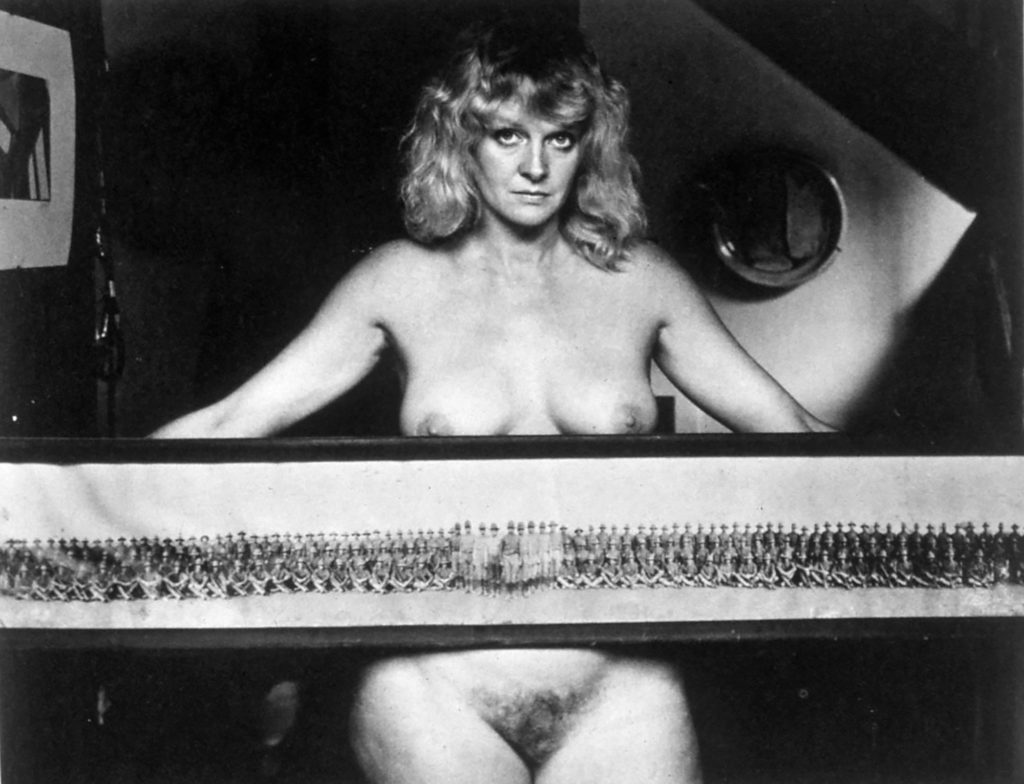

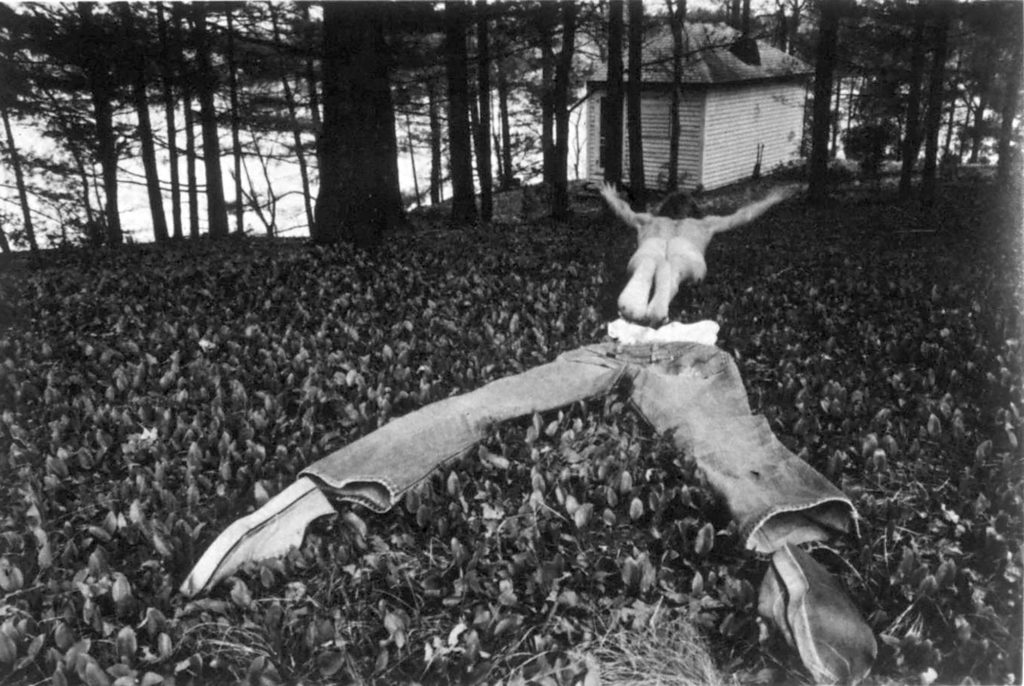

The darker humor that surfaced in the 1960’s (see last blog On Humor, part one) is well represented in art as well. The humor of the Dadaists, Surrealists or even the Pop artists, tends to be lighter in nature than the dark humor found in contemporary art today. Despite the nature of humor, humor will most always have clever wit to it. I would make the case that clever wit most always has at least some element of humor as well. Sometimes the humor is in the message and often it is used in the delivery to soften the message. Here are a few examples of some extremely dark humor found in the parodies of contemporary photographer Joel Peter Witkin.

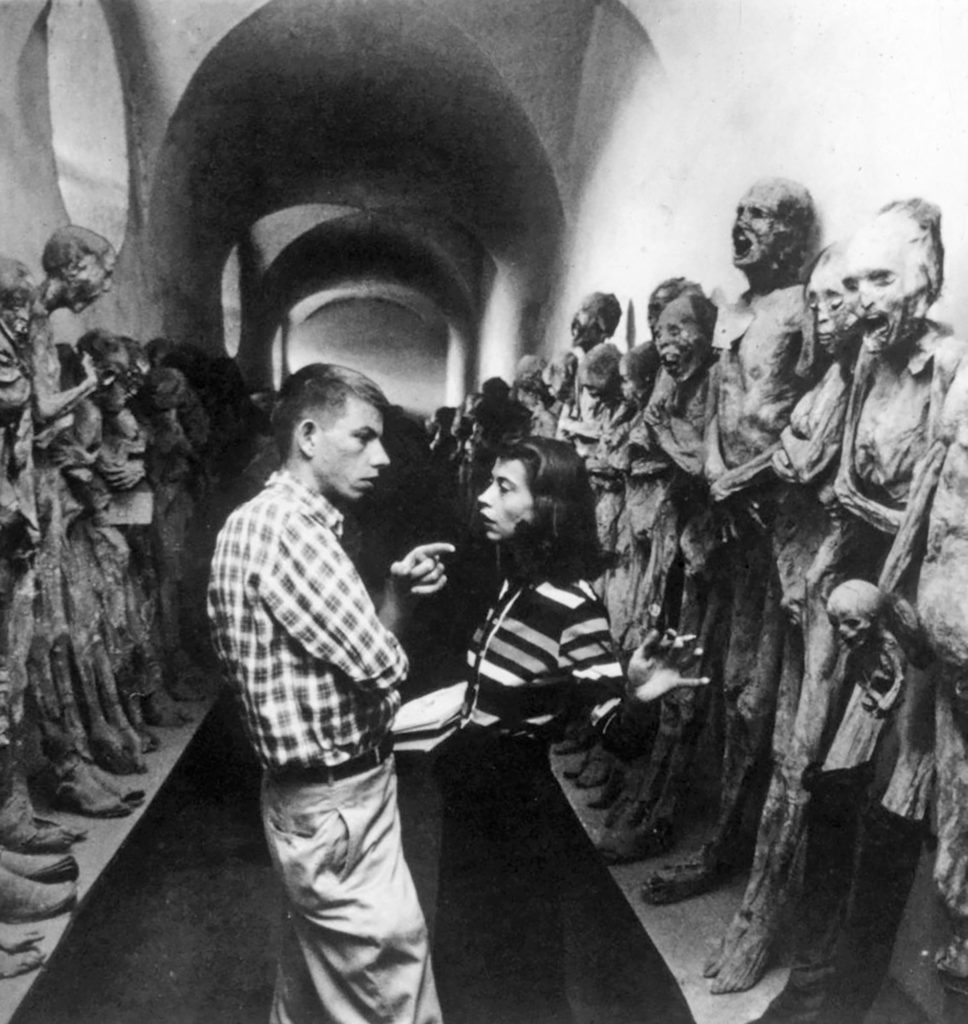

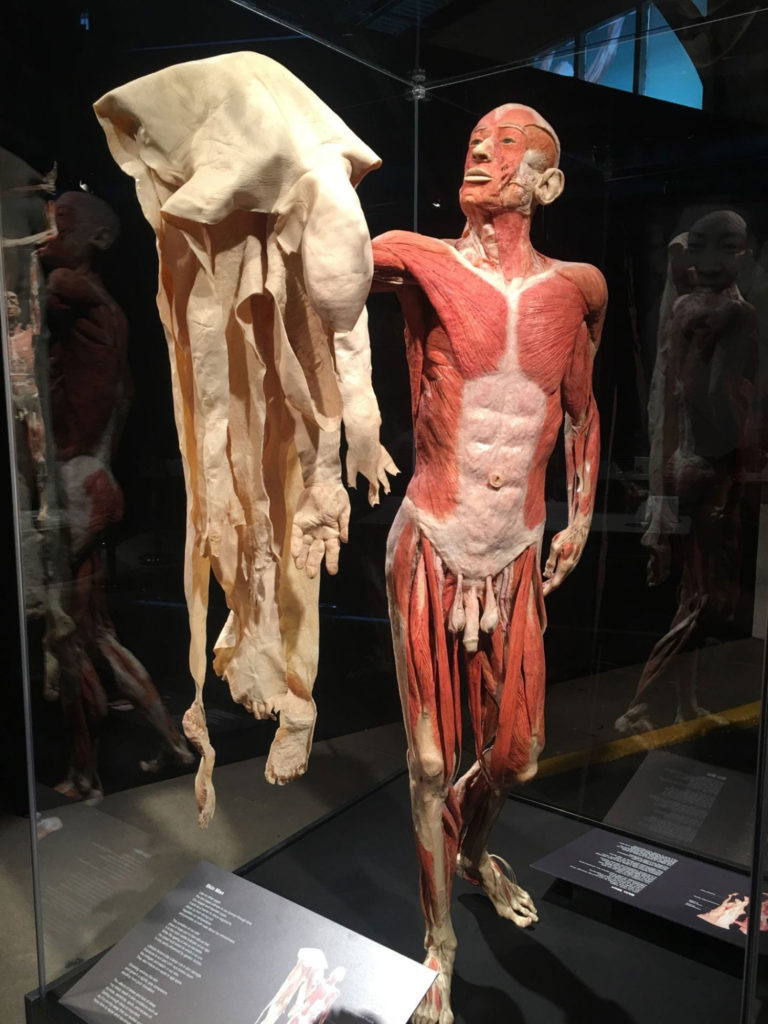

Cadavers have always been a source of curiosity and exploration throughout history. Body Worlds is a traveling exhibition of dissected human bodies that have been preserved through the process of plastination. In 1977, Gunther von Hagens developed this preservation process where the water and fat are replaced by certain plastics, yielding specimens that can be touched, do not smell or decay, and even retain most properties of the original sample. The exhibition was so widely successful that there have been six Body Worlds to date. When Body Worlds began touring museums in the mid-1990s, it tapped into a human curiosity that has probably always existed – the fascination with death and the human body with an almost insatiable thirst for seeing scientized dead.

The creator of the exhibit considered the works his art and signed and titled them all. Some were even parodies from art history such as Salvador Dali’s woman with the drawers coming out of her body. If this exhibit were to be exhibited at an art museum, it would raise condemnation. Yet under the guise of science, the same is no longer taboo. I doubt if very many people experienced the exhibit as a science experience but the audio players everyone wore told them in clinical detail how they should be seeing what was in front of them. However, people see what they want to see and I remember a young child being so mesmerized when looking up close at a man’s flayed penis and testicles that the father could not pull him away and did not know what to do. Personally I found the only way to tolerate the sacrilege in front of me was to tap into the humor of it all. Such exhibitions certainly face the public with their own mortality, and other existential questions, but the statements that most of these human sculptures posed where simply bizarre jokes.

Everyone sees themselves in these corpses. As such, the sanctity of the human body raises controversy about the sourcing of actual human corpses. Von Hagens maintains that all human specimens were obtained with full knowledge and consent of the donors before they died (registering 19,000 donor volunteers worldwide for his art), but this has not been independently verified and in 2004 Hagens returned seven corpses to China because they showed evidence of being executed prisoners. A competing exhibition, Bodies: The Exhibition, openly sources its bodies from “unclaimed bodies” in China, which can include executed prisoners.

Damian Herst has made his reputation using wit and humor to deliver some very taboo and grotesque content resulting in some very engaging conversation and controversy. Artwork like Witkin’s and Herst’s often set the psychology of attraction and repulsion in motion, arousing much emotion to keep us coming back for more like the taboo attraction we experience when trying not to look at a car accident.

One of Maurizio Cattelan’s best-known works, The Ninth Hour represents Pope John Paul II dying on the ground after being struck by a meteorite. The title of the work alludes to the moment when Christ cries out : “Why have you forsaken me ? “ and then dies on the cross. This hyper-realistic sculpture of The Pope being hit by a meteorite is a provocative statement calling the Catholic institution into question with a sense of dark humor. As with much of the dark humor today, the humor stems from disillusionment and aims to disturb, call into question and wake people up.

As in most perception, what the observer brings with them in their mind plays a major role in what they see. The way we perceive anything is effected greatly by what we know or believe. Do you remember what your reaction was to this Van Gogh painting earlier in the blog? Does it change your perception of the painting if I told you this was the last painting Van Gogh painted before he killed himself?

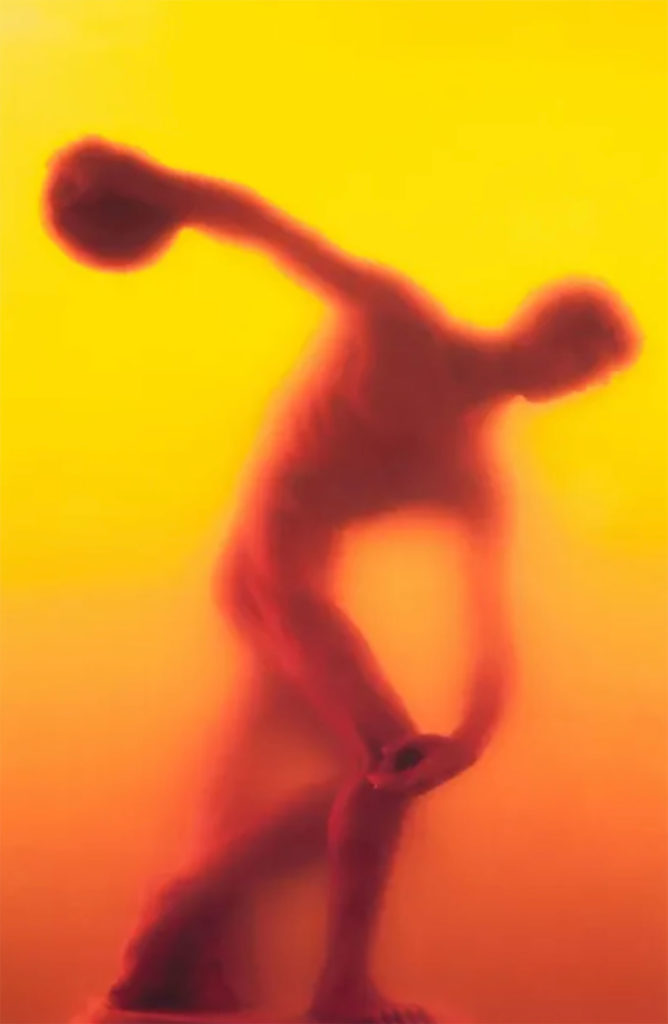

The following are beautifully colored, dream-like images of Christ and The Thinker by Andres Serrano.

Does it change your perception of these images if I told you that they look the way they do because they are encased in Andre Serrano’s piss?

Banksey uses his art to criticize authority and protest. His images usually have dark humorous aspects about them. This humorous graffiti appeared on the wall of a prison overnight and is speculated to be his work. The picture shows a prisoner, possibly resembling the famous inmate Oscar Wilde, escaping on a rope made of bedsheets tied to a typewriter. The jail brutally imprisoned Wilde in the late 1800’s after his affair with Lord Alfred Douglas was exposed.

Humor in art offers us some distance and some reconciliation of opposites. Humor in light of the gravity of the world’s problems also allows us to distance ourselves from our fears and despair. In so doing, humor offers us a type of defense mechanism that encourages us to go on despite the horror that surrounds us.

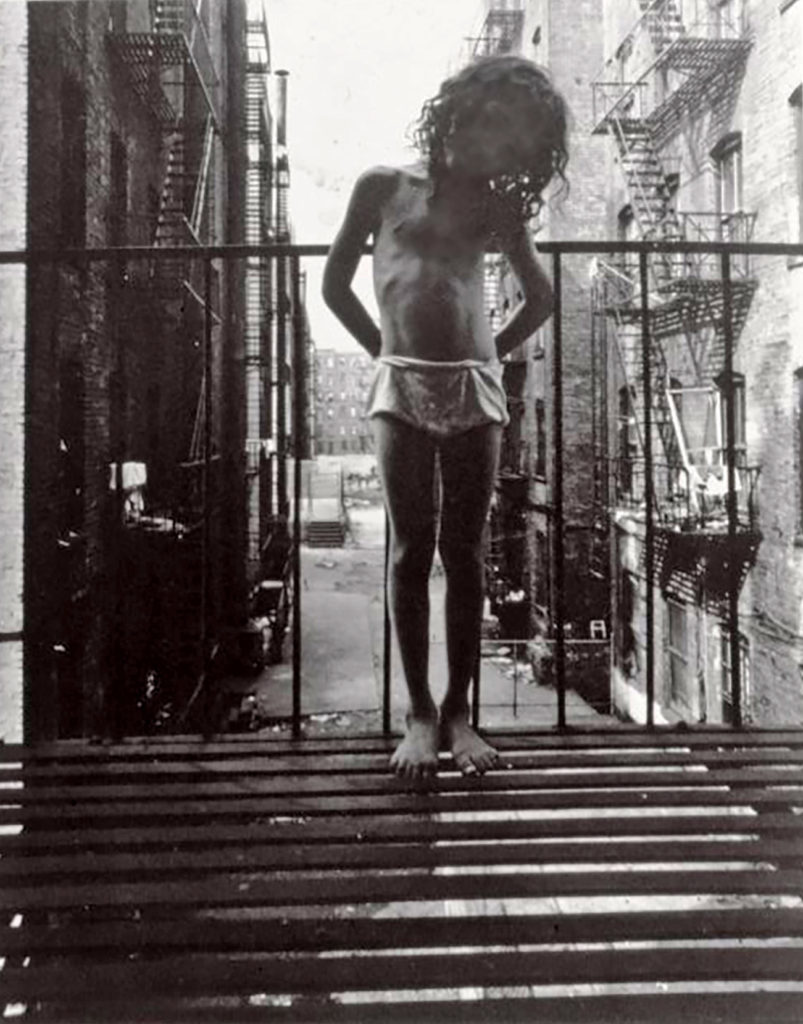

For me, humor is a way of surviving the pain of life. There is beauty in light of pain that offers salvation. I find humor a meaningful way to process suffering and rise above the base horror with hope. The following images are a few more from my series All Things Peeps that are in response to various social issues of horrific nature.

I make art in order to go on living – to survive. It is my way to process life’s pain. The following two images represent the flavor of my dark humor in response to the pain I feel in life. The wit and humor in these images offer a perspective on the dark side.

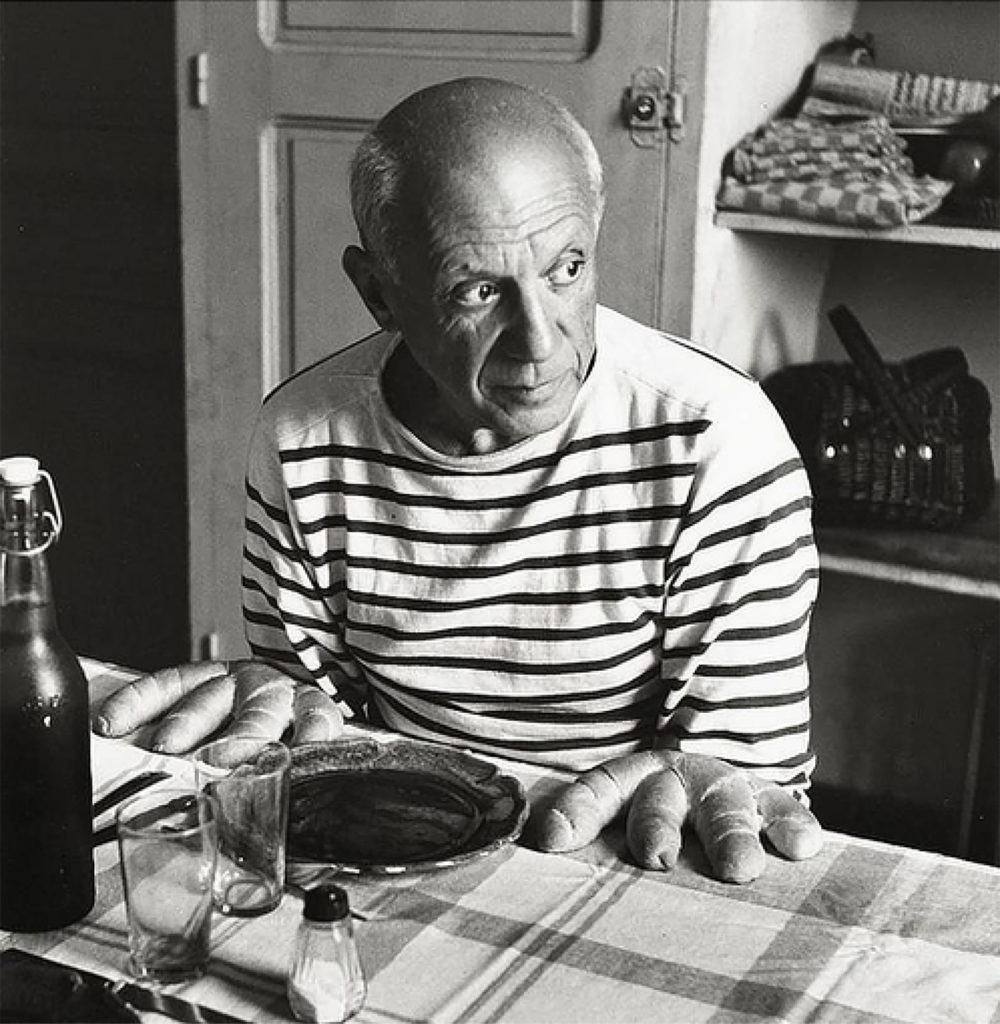

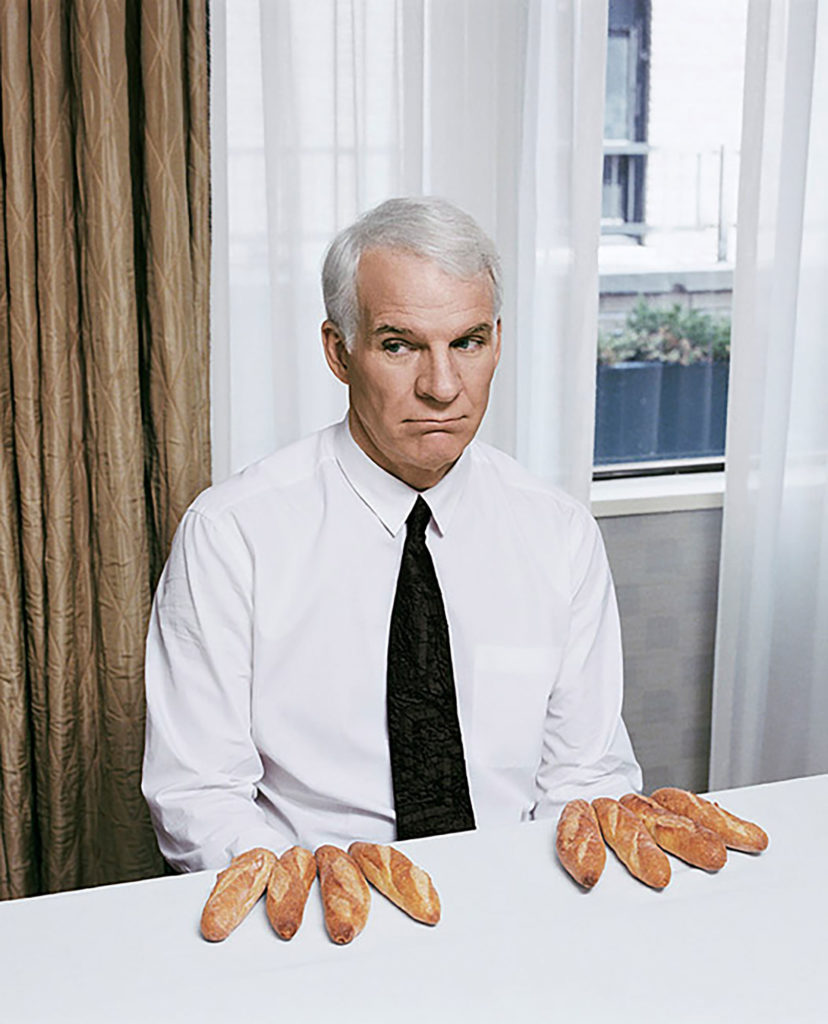

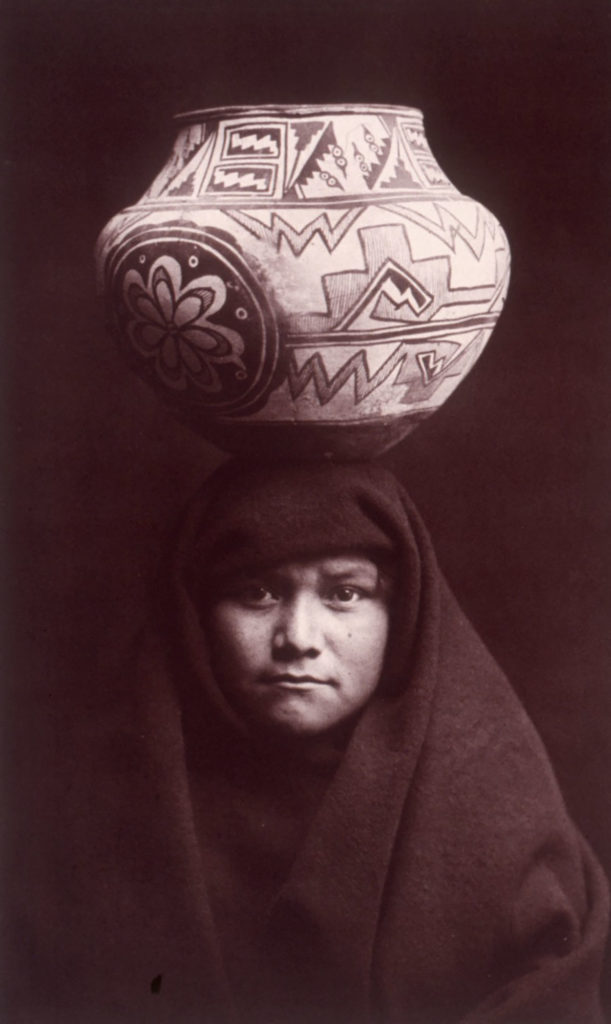

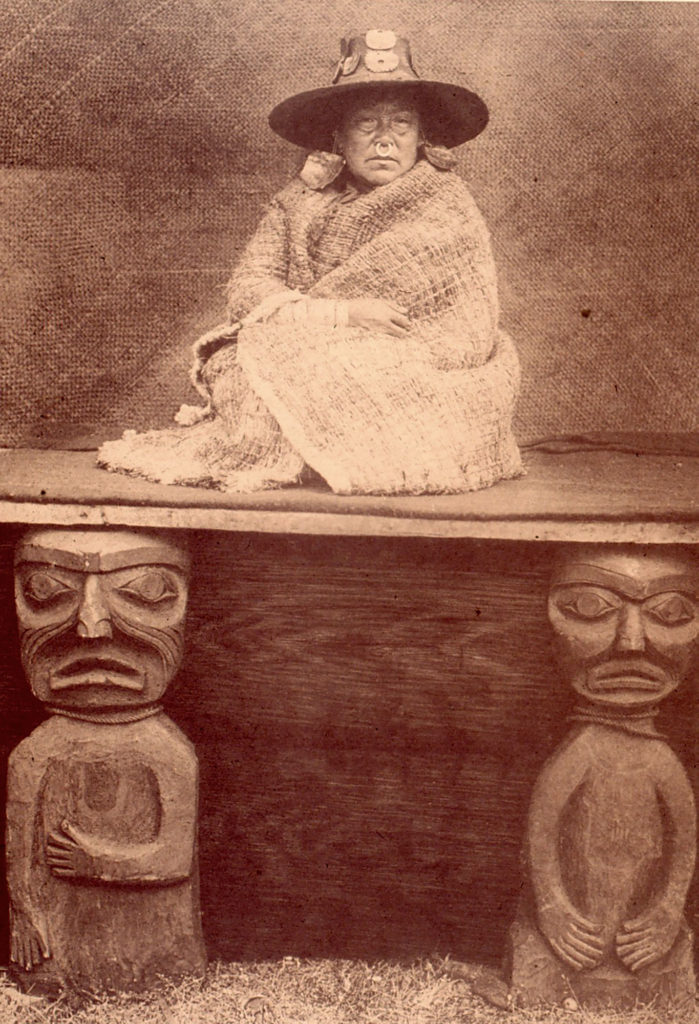

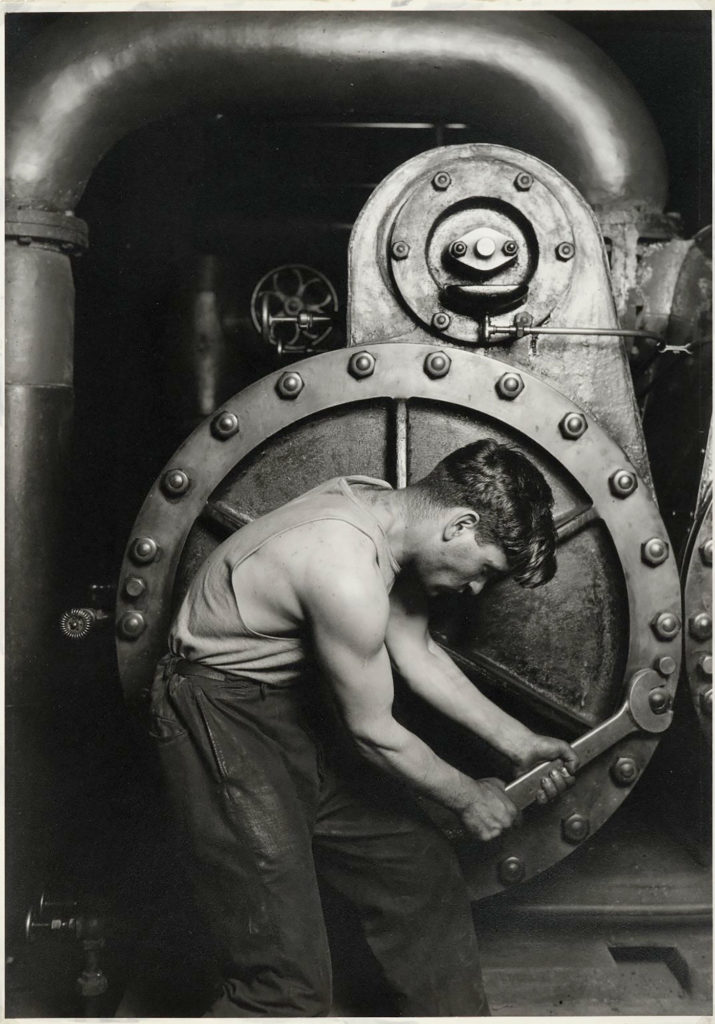

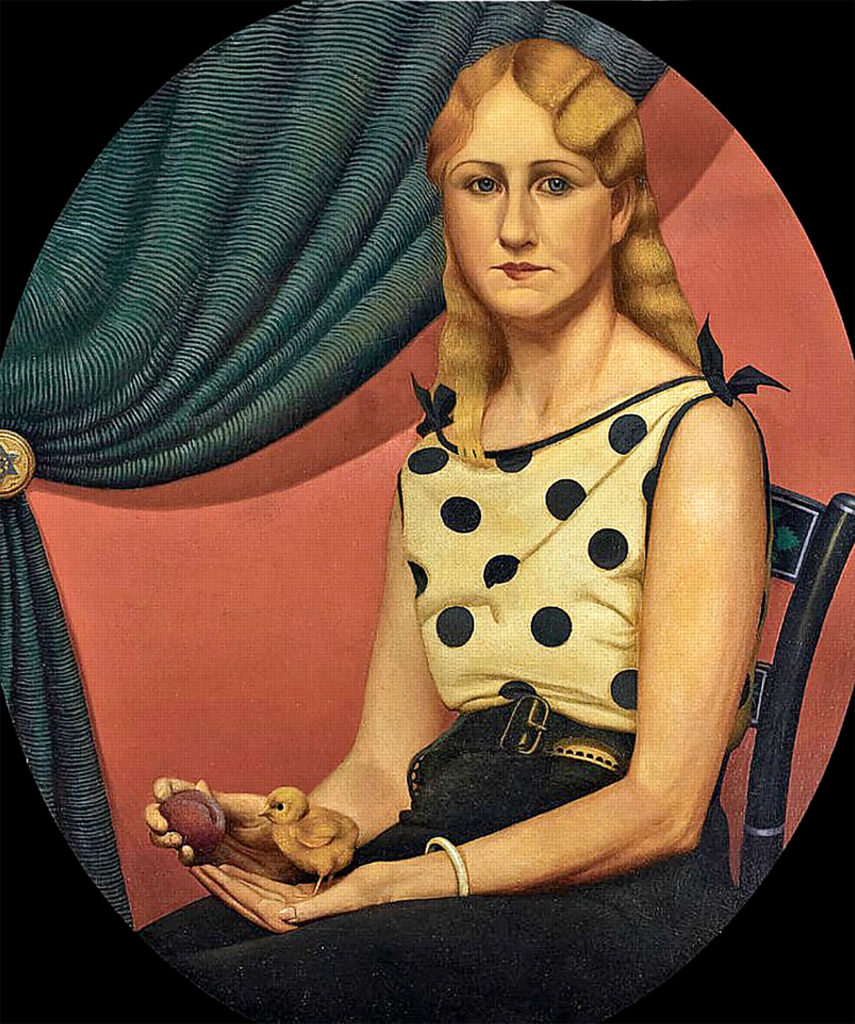

In tying up this vast and bottomless topic, it needs to be pointed out that although humor in art can be overt, usually humor in art is more sublime and simply a part of the transcendent nature of art. The following representations are not visual jokes or puns but do possess a sensibility that reflects the gentle, sensitive pleasure inherent in the image-making process itself. Often something amusing is in the mix of why we see something as beautiful in the first place. I find a light-hearted wit in the metaphors alluded to in the following historical images.

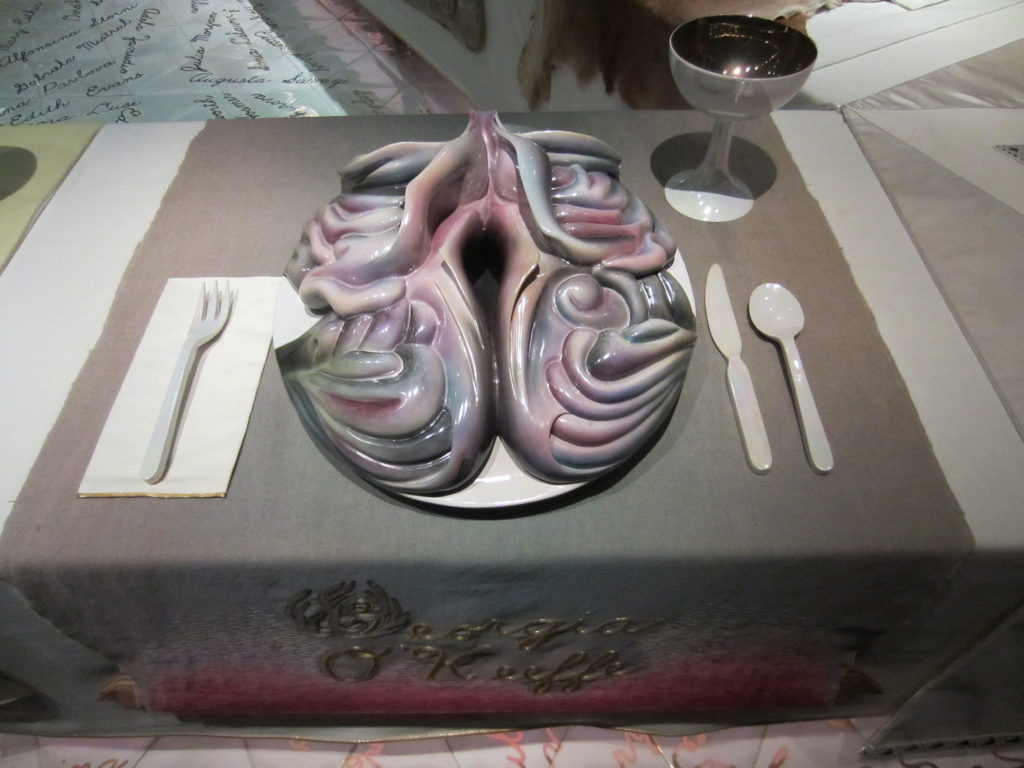

Georgia O’Keefe hated it when people thought of her flowers as vaginas, but in all honesty, they are so blatant that it is difficult to deny a viewer this thought. It may be the nature of a flower to attract pollen in order to procreate but they are not vaginas. Even Judy Chicago saw them this way when she made her famous Dinner Party with this place-setting for Georgia.

Of note: Modernist photographs by Georgia O’Keefe will be on exhibit at the Denver Art Museum from July 3-November 6, 2022 in an exhibition entitled Georgia O’Keefe Photographer.

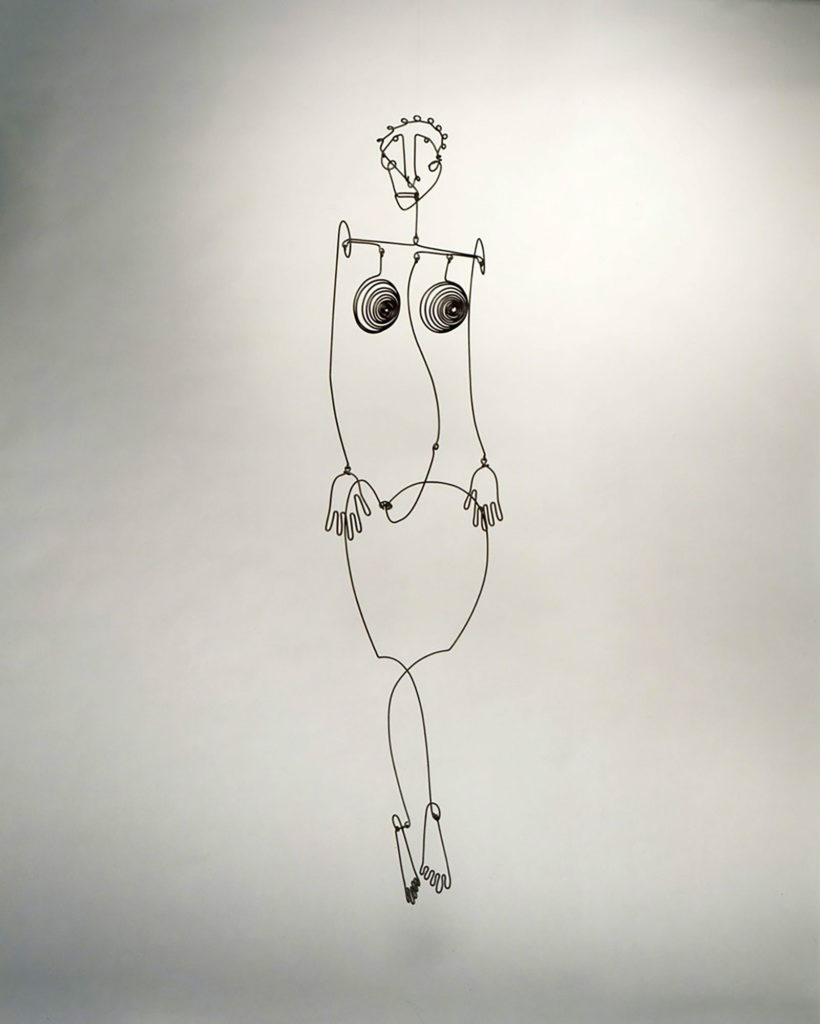

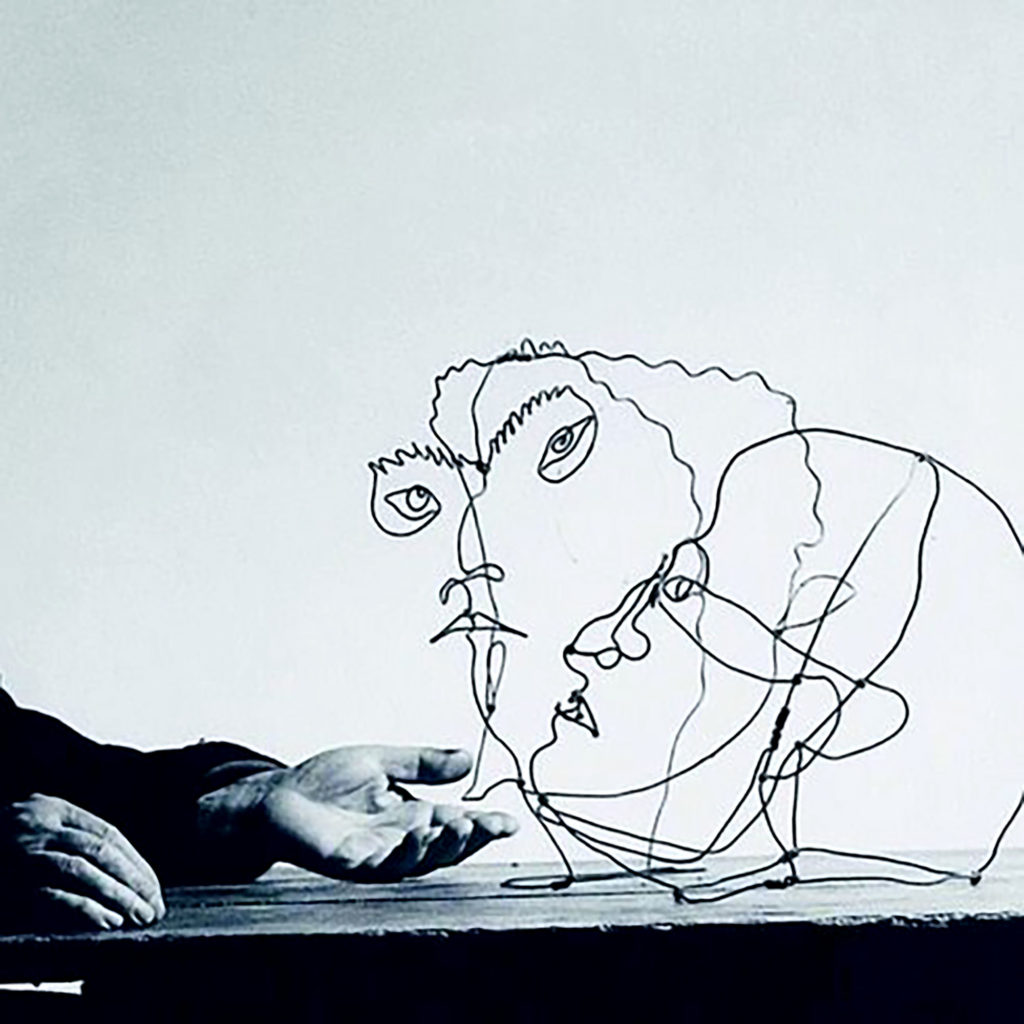

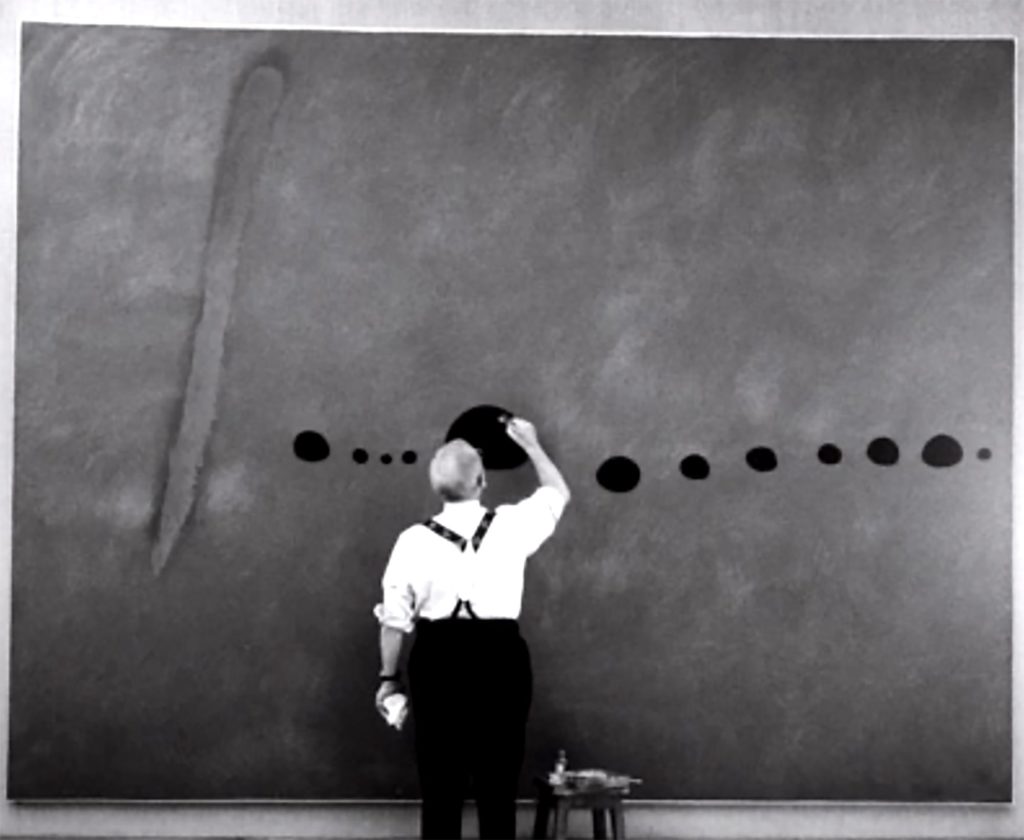

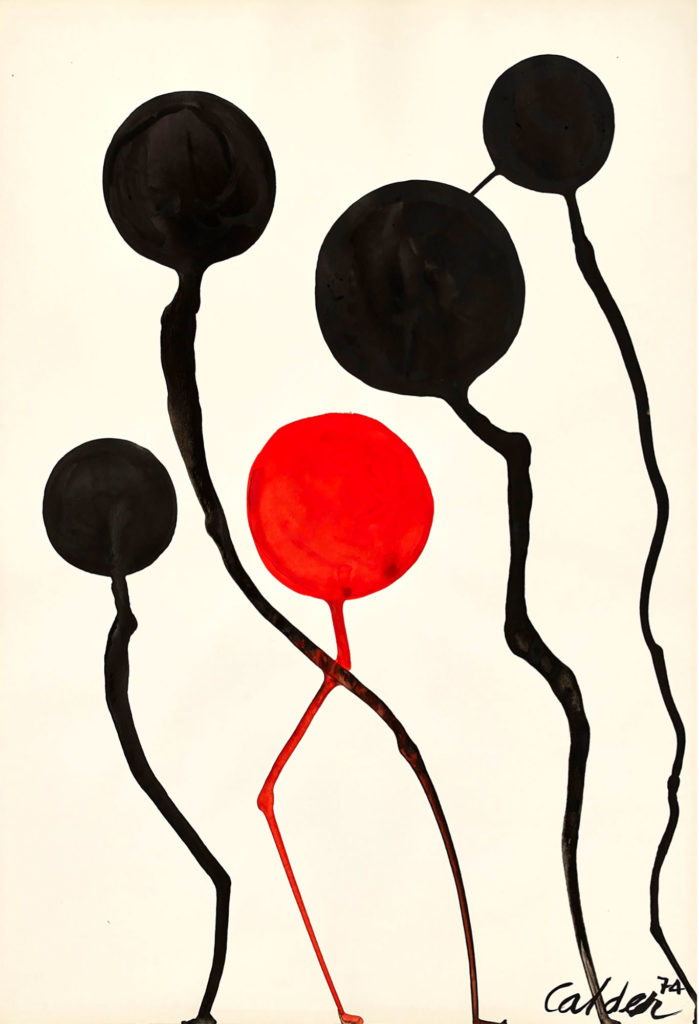

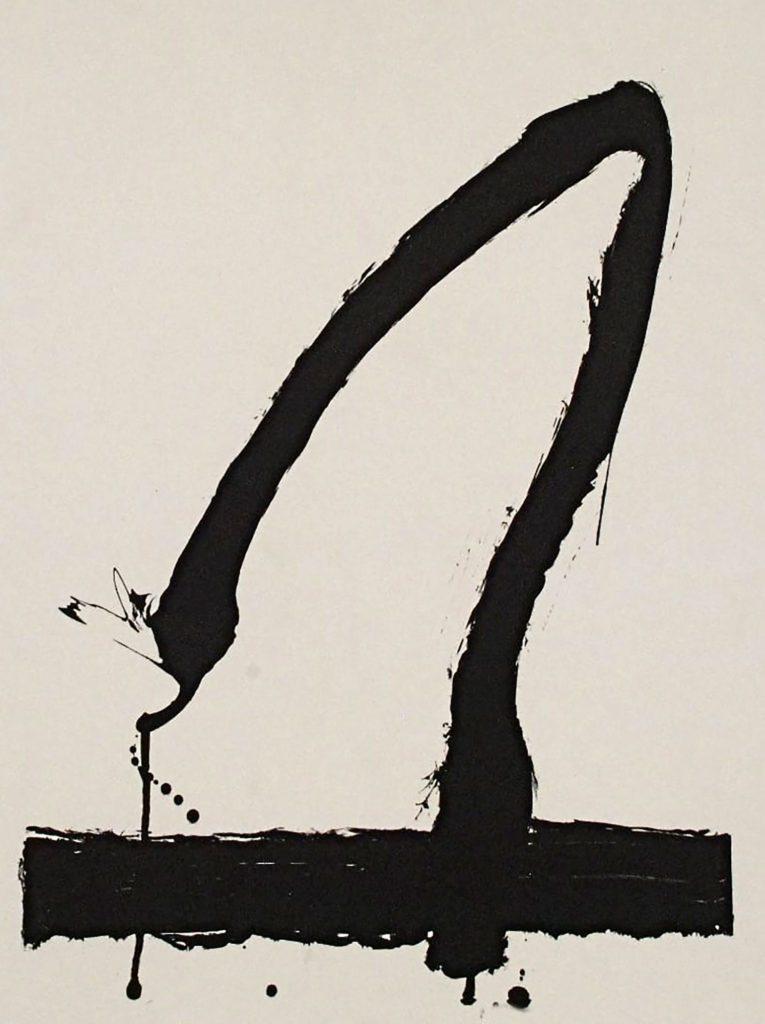

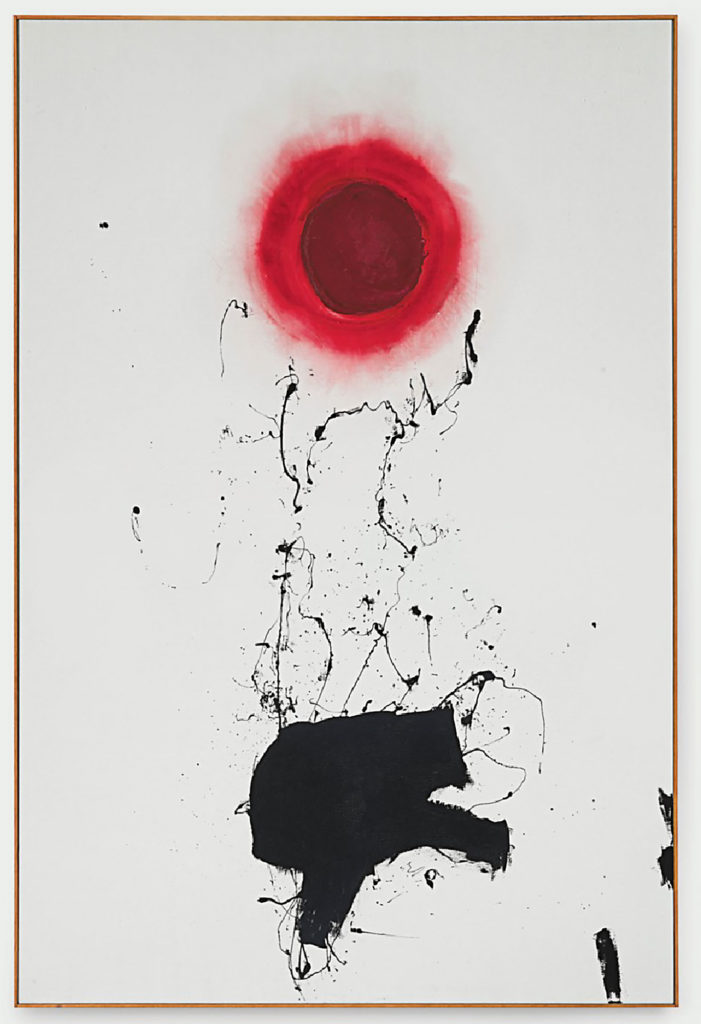

Alexander Calder is known for his playful and lyrical abstract forms. As with many artists, sometimes we can find a key to the intent or the artist’s attitude towards a work in the title. As with most art, especially abstract art, it is not ultimately intended to be an intellectual experience. Robert Motherwell said, “Art is an experience, not an object.” Trying to understand abstract art too much can be unproductive. It is a world where one must be open to just letting the artwork be like a musician playing the viewer. In this state, one might be surprised at the feelings that are triggered.

Understanding abstract art requires an understanding of the expressive nature of visual language and the structure of that language. Visual language is one that uses the expressiveness of visual elements to create a statement. In this case, the language is one of formal elements such as composition, color, shape, form and the expressiveness of gesture in the mark-making. These formal elements can be the subject matter in themselves without representing something else. Abstract art is a language of visual feeling, emotion and even transcendence that can perhaps be described as visual music. Emotional readings can result from an organization of space, the psychological effect of color, the expressiveness and character of a line or the relationships between shapes that can form tension, harmony, dominance, sub-dominance, movement, etc. Often a humorous attitude can be mixed into the lyrical complexities of an image.

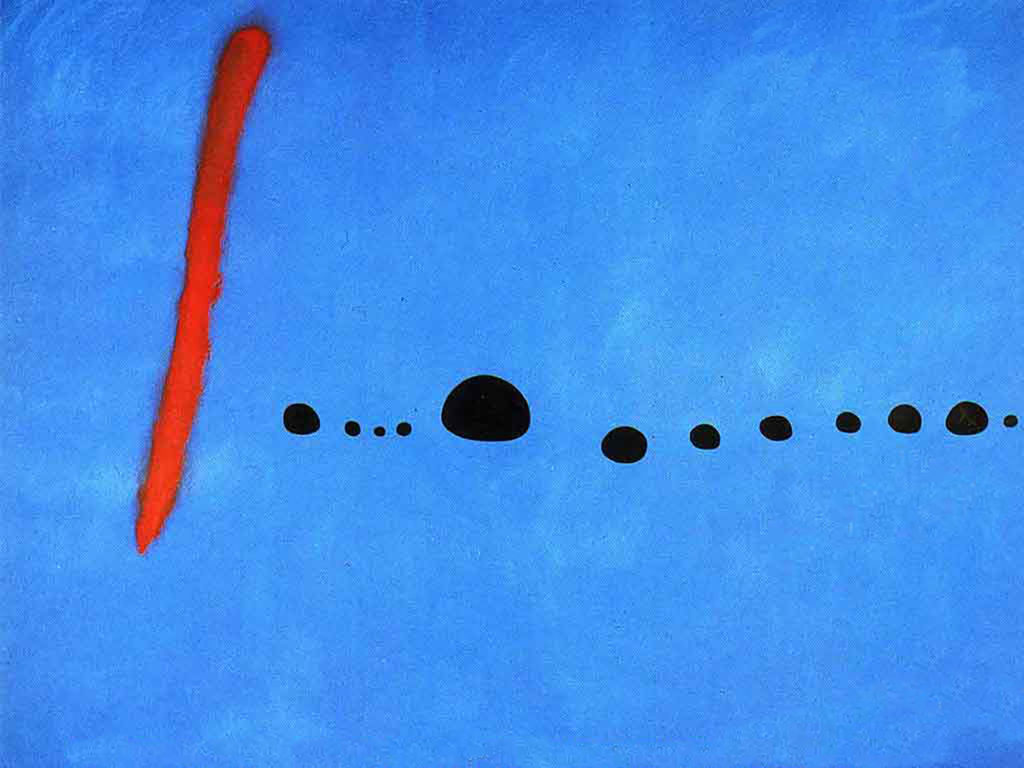

Once a certain amount of visual literacy is achieved with the vocabulary, these abstract elements can be understood in serious or playful, whimsical and even humorous ways. In the following images, look for some aspect of humor, amusement, playfulness or wit in the expressive relationships between the formal elements. In many cases, it is simply a visual feeling that may evoke an inner smile.

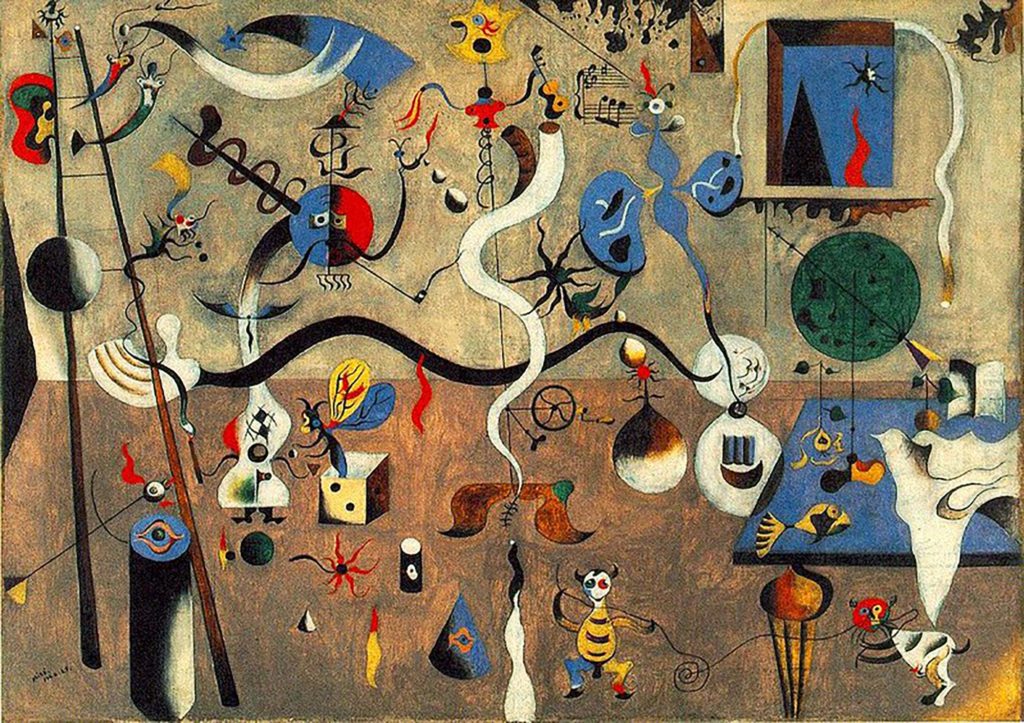

In this rather figurative painting by Joan Miro, one can see the way in which Miro’s mind works in a playful manner with his forms, shapes and relationships. The same thinking , sensibility and playfulness is present in his more abstract work.

When a piece of art evokes an inner smile of sorts in me, I make the case that somewhere in the complex perceptual tapestry is a thin veneer of humor. I don’t have to think about it a lot, something inside is triggered that causes an inner smile to occur in recognition of the wit and attitude behind the relationships of the visual elements in front of me.

Both art and humor are a uniquely human experience and are overlapping threads in the complex tapestry of what makes us human. They are both expressive tools that help us to understand, to cope and to find hope within an ever challenging world.

Patty

What an incredible post! I am always enthralled by the combination of the story and the images. It’s incredible how much depth and detail you share in your blogs. Thank you for this!

Dave Yust

This was just BRILLIANT! Thanks for sending!

Sharon Brown

You always astound me. You are so learned, so insightful, so articulate. How you collected and organized the art is a huge undertaking and you made it seamless. Loved seeing Steinberg and Escher again. This should be required reading in art classes. . Loved it and you

Ivar

My absolute favorite visit to the MCADenver was a few years back when they had comedians do tours of the museum exhibitions. There is nothing funnier than laughing at contemporary art! And those who collect it are mostly very humorless, at least that was my takeaway when Bull Amundson served as mc for the dam contemporaries annual gathering. I was busting a gut while everyone else mostly sat stone faced wanting to get out of there! Thanks for the insight John

Suzanne Hunt

This one was beyond humor, John. And one of the most intellectual views of humor (dark humor) I have ever seen, which of course we would expect from only you. ha ha! Fascinating to read about everything. The making of fake food for restaurant displays really struck me. Who knew? And the cadavers in action. Your peeps always tell such a story, even in ginger. So much to digest. . . .

The photos pulled you in, mesmerizing you — but had the effect of twisting your mind. Some of it was very fun. However, I must admit that I was cringing as I processed some of the images. But I expect that was the intent.

Enjoying all the many facets of your work. Thanks for sharing!

Timothy Batton

John, thank you again for adding spice to my life, as you always do. This Chapter screams to me that organizing and presenting various art forms is art itself. Your comments and observations frame each segment so well and give context to us novice types. I am so looking forward to a next installment! It seems to me you are creating your legacy. I am always grateful for to have you in my life. I love you brother.

Rex Brown

FANTASTIC! BRILIANT! A gift for all of us in this not funny era. Thank You!!!