Stories from the Hood, Part Four – The Flag

Stories from the Hood

The Flag

Chapter Four

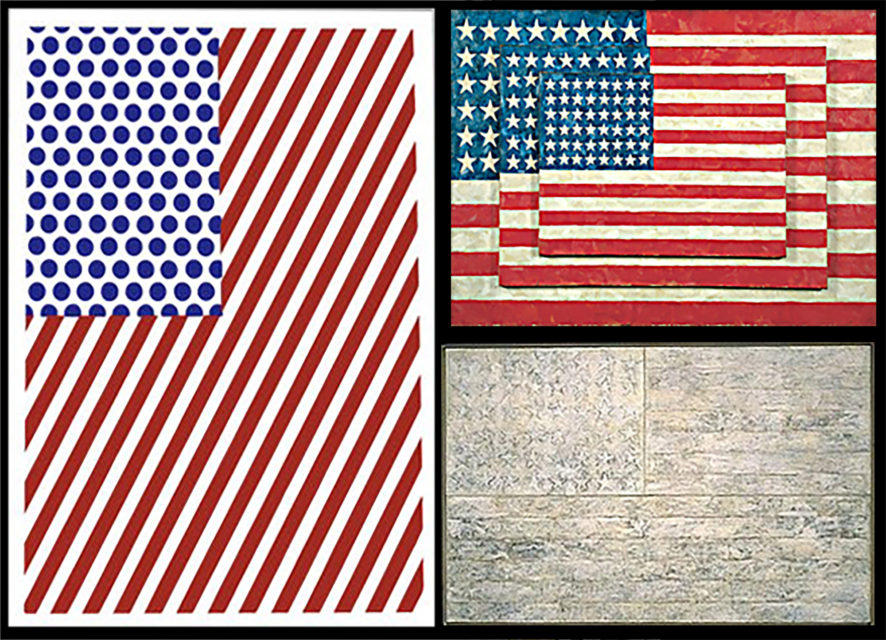

The stories about what it means to be American are as diverse as this nation itself. Although we all have our own ideas on what it represents, the single symbol that encompasses it all, is the American flag. This blog focuses on three stories that describe three major events connected to my experiences with this icon. Flags are by nature political, but what is deeper is the bottomless cultural history they embody. I prefer to see the flag on my house as a reminder of something greater than the specific political events that surround any given day. The flag on the outside of this house is for everyone and has a life of its own.

This particular flag’s child-made style gives it an innocence, speaks of the next generation of Americans, and gives a perspective on our country’s future. Designed by a 5-year old, it has an unknown quantity of stars and the stripes do not conform to geometric accuracy – a unique take on the familiar icon. As with most public art, it has become a landmark that embeds itself into an identity of place. I see it as a Pop icon, much like the gargoyle described in the previous blog.

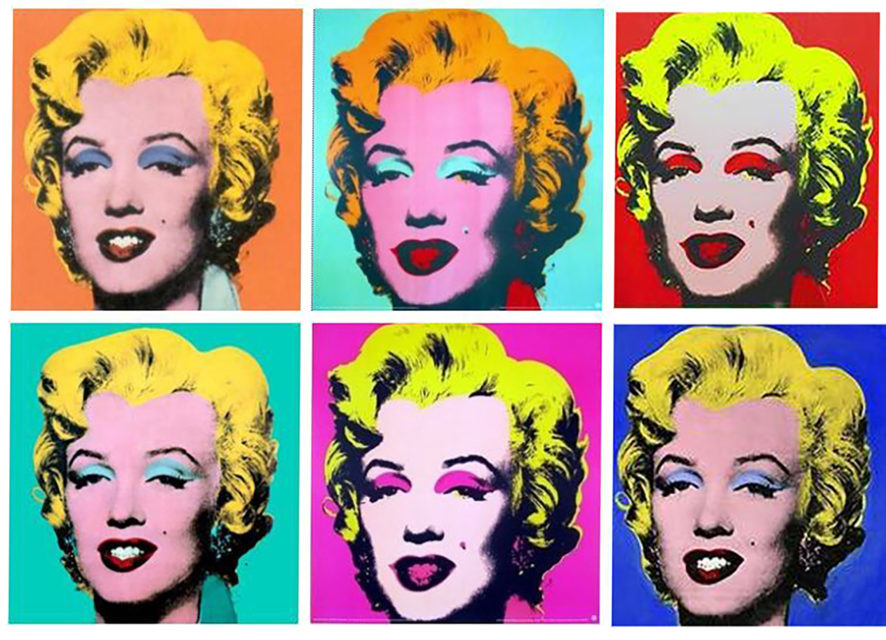

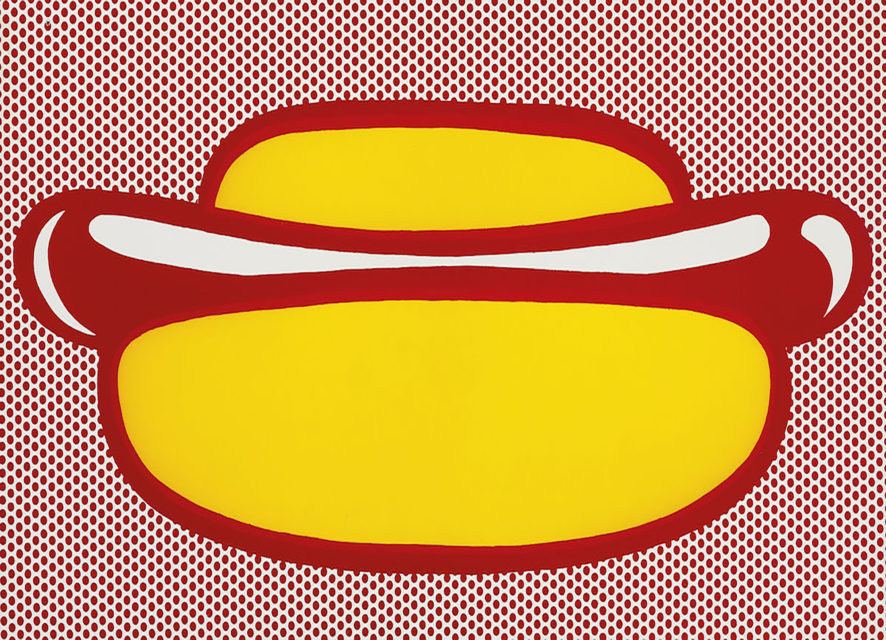

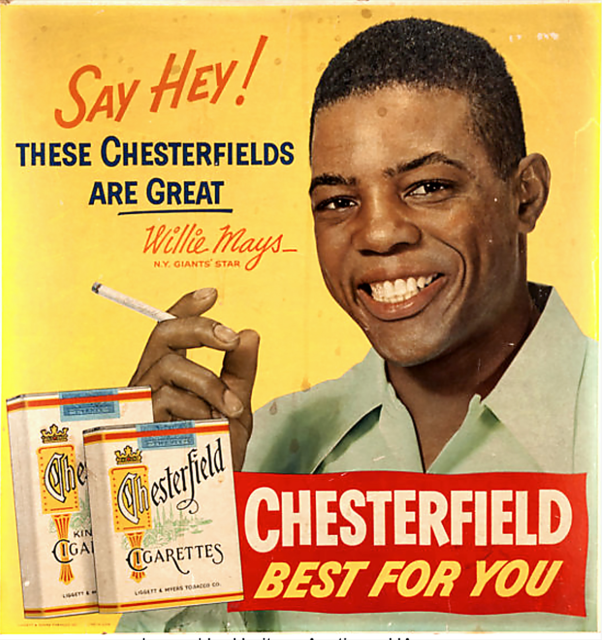

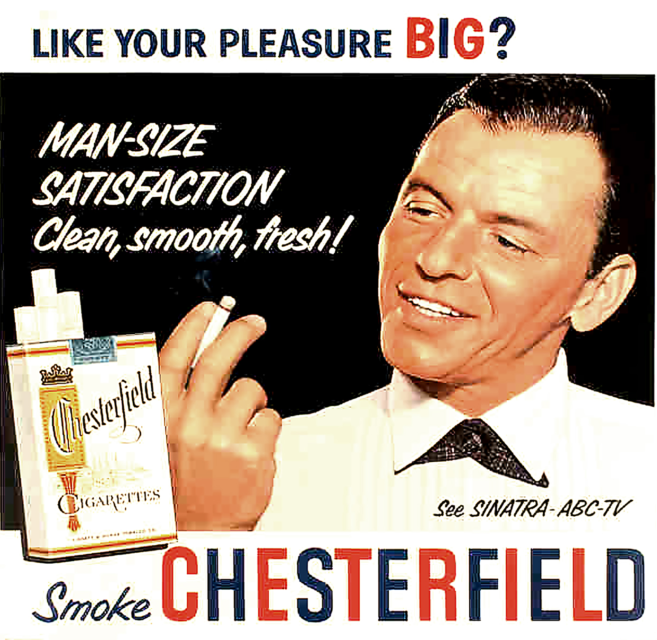

When people relate to the art on this house, it is through the lens of popular culture and as such, has much in common with the Pop Art movement. The Pop Art movement began in the 1950’s in response to American popular culture and the mass consumerism that followed WWII. Pop Art followed on the heels of the Abstract Expressionist movement with the reintroduction of recognizable imagery. But Pop imagery was new to art. The subject matter in Pop Art imitated and was drawn from mass media and the not so “fine art” of popular culture. This new visual subject matter was colorful, fun and playful. It focused on such icons and commodities as celebrities, advertising, comics and commonplace, often mundane subject matter. Andy Warhol was the undisputed king of Pop Art and today his prints of Campbell’s soup cans, Brillo pads and Marilyn Monroe have become as iconicly American as the American flag itself. What we feel when looking at an American flag will vary, but it is a complex emotion that includes the American culture along with anything else.

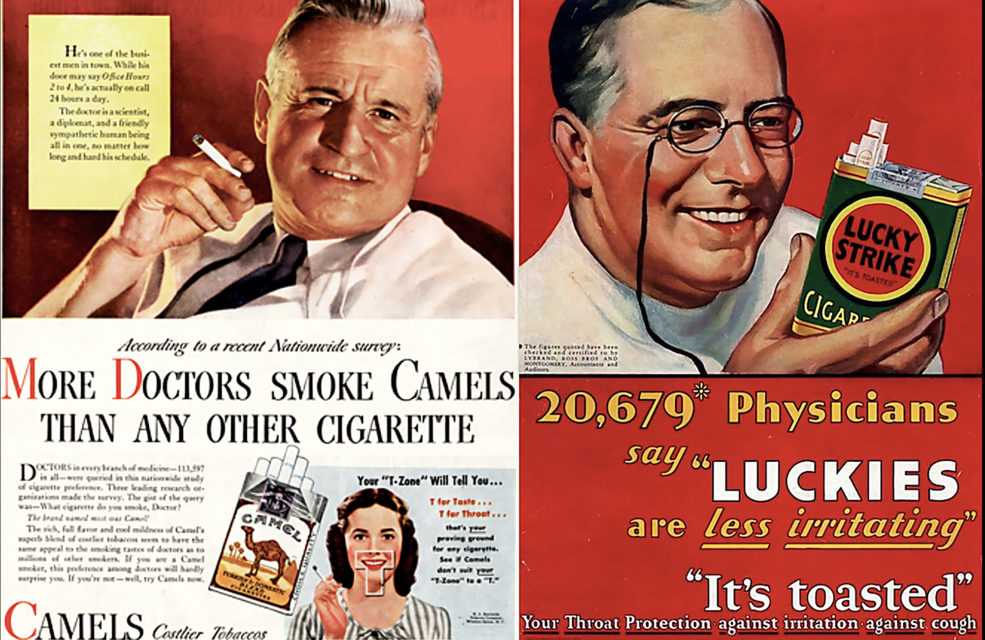

I grew up in the countryside of northern Ohio. As a baby-boomer born in the early 1950’s, life was much like that portrayed in the Netflix series Mad Men. Early childhood was amidst a culture of extreme conformity and mass consumerism. Status quo for the perfect life proliferated the media through ideas of correct behavior, product consumption, ideal role models, good and bad; black and white ideals that most Americans aspired to in the post WWII era. This repressive first decade of life was followed by growing up in the dramatic cultural revolution and violent turbulence of the 1960’s, characterized by non-conformity and a questioning of all that preceded it. These two decades rebounded off each other and formed my identity as an American.

My family lived in a brick house that my father built. The neighborhood consisted of six other houses with an abundance of undeveloped land and vast woods which I spent much time exploring. Our house had a tall flagpole in the front yard from which the Old Glory always flew. Next to us was an empty lot that my father mowed with his tractor; this grassy patch was used as the neighborhood baseball field. There was a rural airport nearby for small propeller aircraft. It was called Welcome Airport. It had a short landing strip, a single building, and a flag pole that flew an orange windsock with the word “Welcome” on it. I passed by this little airport almost every day for one reason or another. It was a fascinating place where little planes were always taking off and landing. The impressions it left inspired me to build model Piper Cubs.

When I was barely two-years-old, an event occurred that burned itself into my young memory for life. That Sunday began typically enough. Half asleep and grumpy, I put up the usual resistance to being forced into uncomfortable clothes for church. My father was smelling his Sunday best with Vaseline hair tonic, Old Spice after shave and the ever present odor of stale cigarette smoke. We got into our classic, blue 50’s Chevy, my father lit up a cigarette and we were off. After getting my share of second-hand smoke in the car, we sat on very hard wooden pews while a man lectured everyone for what seemed an eternity. The seat backs were lined with books which everyone periodically searched through, then sang words in unison. My mind was preoccupied with getting back home. The day before, my father had visited some friends of his that worked at the local cemetery and he brought me back a little American flag. I wanted to get back to my new toy.

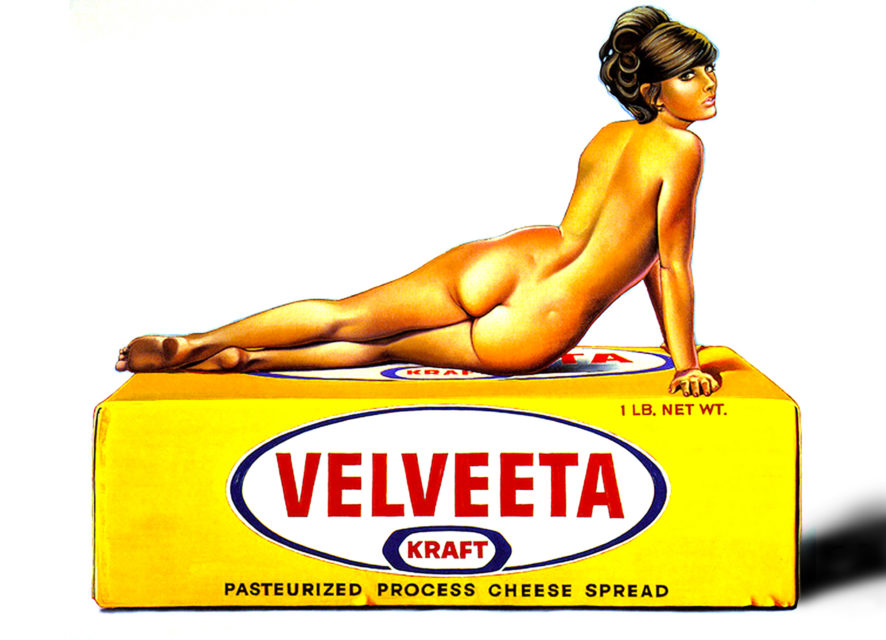

When church was over, everyone piled outside to smoke cigarettes and socialize. I silently waited this out and was once again entombed in the smoke-filled car for the drive home. By the time we got home, it was lunchtime. My father and I sat swinging on the porch glider together while my mother fixed up Cambell’s Tomato Soup with grilled cheese sandwiches made from Wonder Bread, Velveeta “cheese” spread and Blue Bonnet Margarine – the family’s favorite Sunday lunch. The ever-present pitcher of Kool-Aid sat on the table; I just had to decide whether to drink it out of my Kool-Aid Goofy Grape cup or my Kool-Aid Jolly Olly Orange cup. I enjoyed sitting next to my father, as we glided back and forth carefree and I played with my little flag. After Sunday lunch, we always went to my grandparent’s house to spend the day with family. This was the perfect opportunity for the wives to try out the latest recipes from Good Housekeeping Magazine ; the recipes featured such classic food-like substances as Kraft Marshmallows, Crisco, Campbell’s Mushroom Soup, Kellogg’s Rice Crispies, Jello, Hershey’s Chocolate Syrup, Velveeta Cheese Spread or Spam (prior to Spam’s Internet fame and the Broadway musical Spamalot). Being together with my grandparents was my favorite time of the week and the day felt just about perfect.

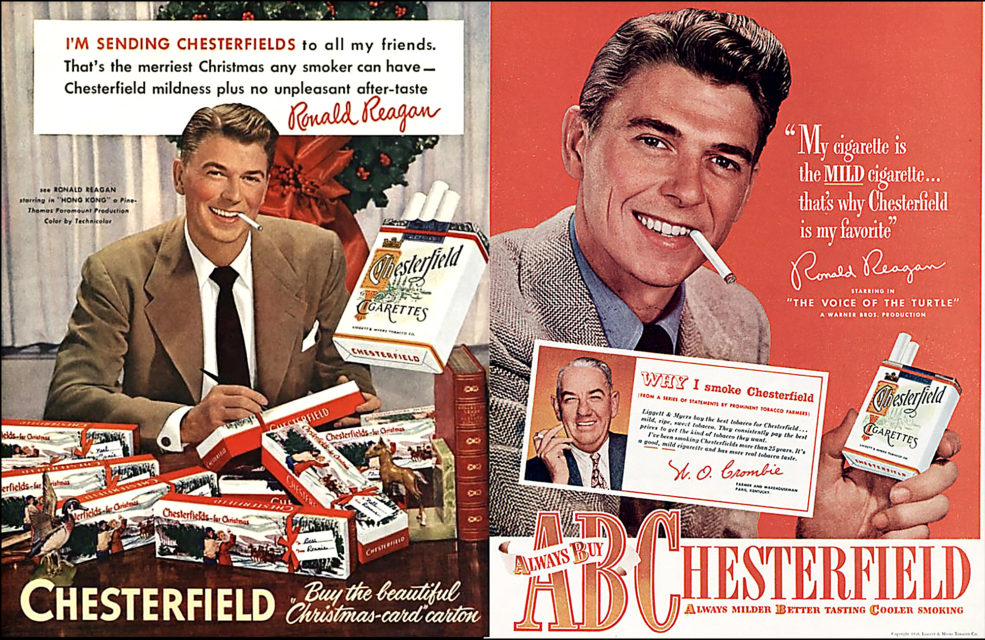

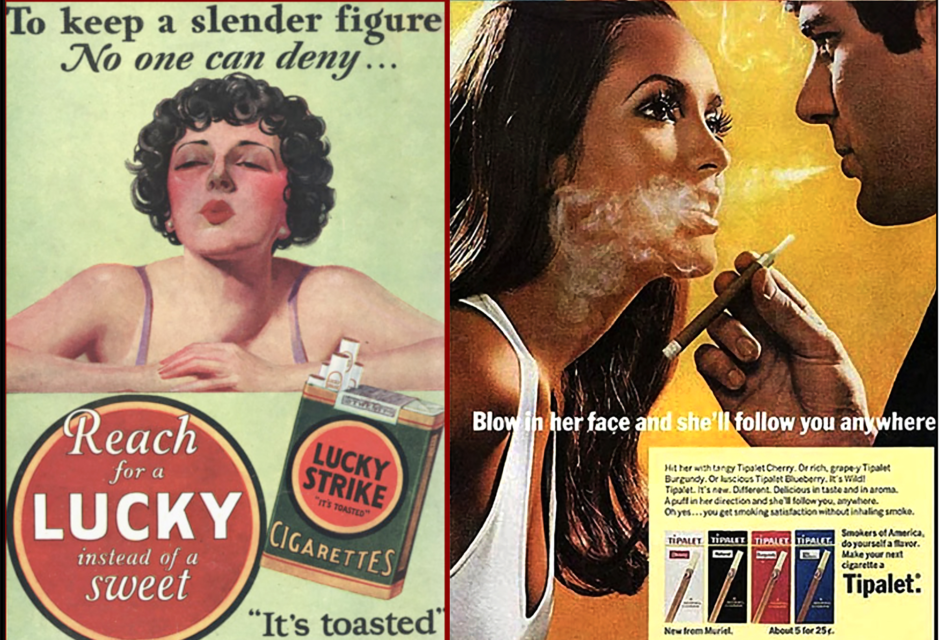

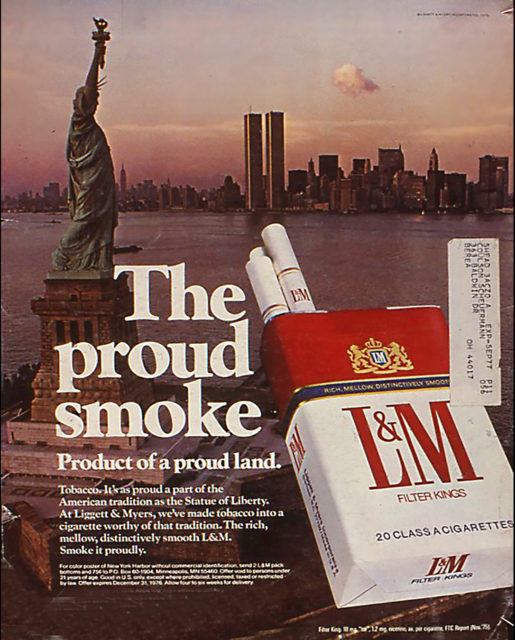

A few cigarette advertisements extolling the health benefits of cigarettes, including my favorites : “Blow smoke in her face and she will follow you anywhere” and a version of the Twin Towers that look like they belong in a cigarette pack.

A gentle summer breeze passed through the screen porch and the flag fluttered in the front yard as we waited to be called in for lunch. We gazed at the empty lot next door; the smell of yesterday’s freshly mowed field was still in the air. For some reason, there were always lots of ladybugs on the screened porch; I was watching one crawl up the screen as my father sipped on his usual cup of Lipton Tea. I wanted to play with it, but knew I had to leave it be. My mother had recently started yelling at me for eating the dead ones. I suppose they were a good source of protein but neither the Betty Crocker Cookbook nor the American Woman’s Cookbook, that my mother swore by, had any recipes which included this ingredient. I was aware that my mother had alerted my father of my new interest. He also noticed the ladybug, so for the time being anyway, I just sat there playing with my flag while the ladybug crawled up the screen, and from my seat on the glider, watched my prey as I waited for lunch.

Suddenly out of nowhere, there came a descending noise that grew louder and louder. My focus shifted from the ladybug on the screen to the empty lot beyond, while a small airplane crashed in the lot right in front of us. There was smoke, then fire. I dropped my flag as my father threw me on top of his shoulders and we bolted towards the smoking wreck. I had a very good view from atop my perch as a pilot emerged in flames and fell to the ground. My mother ran out with blankets. It was my first smell of burning flesh.

My father was strong from shoveling coal for a living and easily carried my light body around with him all day as he talked to the fire department, the police and all our neighbors. I just quietly absorbed it all like a sponge and held tightly onto my little flag. I couldn’t comprehend what anyone was actually saying but was very aware of the serious tone and emotion behind the facial expressions. As my father held me up high in his arms, I remember staring into our elderly neighbor’s face as she spoke to my father. Her gray hair framed her softly wrinkled face as she talked with a high-pitched, cracking voice much like a bird – even her name, Leotta Oviatt, sounded like a bird song to me. The oddest details, even smell, are often embedded in such a memory mix. Throughout the events of the day, holding onto my little American flag gave me a sense of security, much like a child might hold onto a teddy bear. The attention people garnished on me because of my little flag did not go unnoticed.

The road leading to high school graduation was a long one, during which, my experience with the American flag was similar to everyone I grew up with. There was the daily conditioning around the Pledge of Allegiance which developed my national identity with the personal awareness that I was a part of something much larger than myself. The 1960’s were never in short supply of “heightened” national events, events that changed history, changed culture and me along with it. A few such memories along the way include being in 7th grade music class when JFK was assassinated, then the assassinations and violence that came to pass with Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King; tearing down the Berlin Wall, the first man on the moon, dancing to the Beatles first album and of course, seeing Janis Joplin perform live on the Ed Sullivan Show. I was the product of a very reactionary time.

While stlll in high school, I came to know Kent State University. From my hometown of Northfield, Ohio, it was only a 20-minute drive to Kent. My “under-aged” high school friends were good at forging fake ID’s. On weekends, our ID’s worked well to gain us entrance into the college’s bars to drink beer. Upon graduation from high school, a number of my best friends went to Kent State University. This was to be the scene of yet another impressionable event.

Life felt like it held me down in high school, much like a tethered balloon. High school graduation cut the string at long last and I ascended to the skies. I went on to art school in Cleveland. On May 3rd, 1970, my roommate and I decided to get away from Cleveland for a couple days and visit my buddies in Kent. We hopped into my Volkswagen Bug and headed out for a good time. As we approached Kent, we thought it odd that no one was on our side of the highway, while the outward-bound side was packed with cars. We just continued on our merry way and pulled into my friend’s driveway. They couldn’t believe we had somehow slipped through as they brought us up to speed as to what was going on.

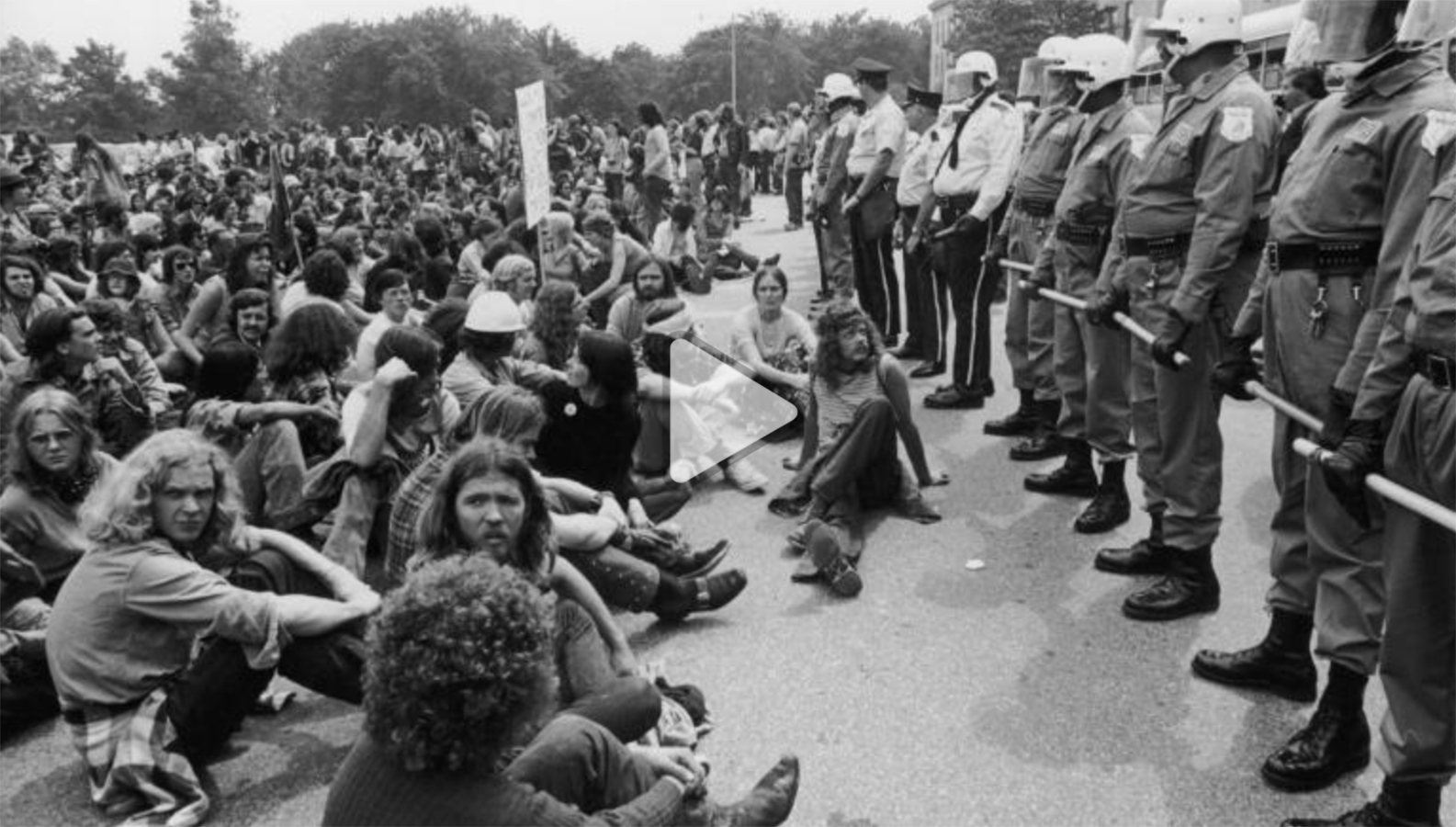

America was in the middle of the Vietnam War. Nixon had just asked the American people to support his decision to expand the Vietnam War with the invasion into Cambodia. On the homefront, the response to the invasion was extreme and civil war was in the air. Demonstrations and riots were happening all over the country. At Kent State University, students stormed the Administration building by force and took it over completely. The university’s president called the state governor, the governor called the White House and a state of Marshal Law was declared. The National Guard was called in and took over the entire city. There were National Guards with heavy duty artillery stationed on every block. All telephone service was cut off; there was no communication link to the outside world. Blockades were set up to prevent anyone from entering. Kent was under siege. No one was allowed to gather in groups larger than two during daylight and no one was allowed out at night; the only exception to this was the “Commons”. The Commons was a grassy area in front of the university’s Student Center building. On one end of the Commons was a shoulder-to-shoulder wall of National Guard containing the crowd.

Night had fallen and a curfew was in effect. No one was allowed out. The only way to find out what was going on was to get to the Commons. So we crawled on our stomachs, darting and hiding behind bushes and trees to slowly make our way. Incidental tear gas drifted everywhere, hitting you when you least expected it. Army tanks patrolled up and down the streets. From above, mammoth helicopters scanned the earth below with their beams of blinding, high-powered light down from the skies accompanied by the maddening sound of the massive copter blades.

It was as if we had been occupied by a hostile foreign military power. I found comfort repeating to myself, “I am inside America. This is the American military. This is not my enemy… I am inside America…” Like a mantra, I repeated this over and over until we reached the Commons. As we approached, the crowd sung out the haunting words of John Lennon in a chant without end, “All we are saying is give peace a chance… All we are saying…” We were powerless without weapons; some of the more radical of the SDS (Students for a Democratic Society) were plotting to smuggle guns in for defense, expecting things to get worse. Other students started throwing rocks at the frightened lines of National Guards. The guard retaliated by tossing tear gas. Some daring students counter-retaliated by running into the gas and throwing the canisters back at the guardsmen. Tension, fear and soon sleep deprivation ran high; the chanting grew to feel like a mesmeric taunt that added to everyone’s deteriorating mental condition. Many of the young National Guard were high school friends I had just graduated with. None of them had any training or experience for anything like this. Everyone was at a breaking point and scared shitless. Such was the state of affairs that continued through the night and into the next day.

That fatal moment in history was simply the result of an escalating pressure that finally exploded. On May fourth, two thousand people rallied in protest at the Commons. It is speculated that one of the guardsmen simply cracked and lost it. He thought he had heard an order to fire. No such order was given. He fired his bayoneted rifle into the crowd and twenty-eight other guards followed his cue. The rifle fire was sudden and was a solid volley of bullets for what seemed like a minute. Sixty-eight rounds were fired randomly into the crowd. We all assumed, beyond any doubt, that they were firing rubber bullets. A short lived assumption when chaotic screams erupted, mayhem abounded, and blood flowed. One of my high school friends was shot in the thigh and fell to the ground. Four students were killed and eleven wounded. Such went down in history as The Kent State Massacre.

That night, massive candle-light vigils were held across the country. Demonstrations occurred in every American city with the goal of shutting down “the machine”. Demonstrators blocked highways with their bodies to prevent commerce; entrance to final exams was blocked at universities nationwide. Four million students went on strike and 500 campuses closed. 100,000 marched on Washington and Nixon took refuge at Camp David. Within days, Neil Young had written the song Four Dead in Ohio ; Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young recorded it and most stations were playing it non-stop. Some stations banned the song. Some news angles even cheered the guards on for killing the students. Such was the chasm of reaction within a country divided. Elsewhere, several connected events resulted in more death and injury. Civil war was in the air. I was emotionally stunned, in shock, and cried continuously for two weeks. Unlike the happy ending in the story of Abraham and Isaac, four American citizens were murdered by their own government and Sinclair Lewis’s book It Can’t Happen Here, was a hard truth learned.

My father always had a flag pole in front of our house and flew his “old glory” with pride every day. The American flag was something I not only associated with my country but also with my father. Nixon referred to the slaughtered kids as “Bums” and that was my father’s take. All over, flags were flying half-mast in mourning, but my father’s flag flew at the top of the pole. I said to him, “I could have just as easily been one of the kids killed. Would you fly your flag at half mast if it was me?” He said, “No, they got what they deserved.” It was at that point that I disowned him as my father for not flying his flag at half mast and he disowned me as his son for needing a haircut. This was not an uncommon family scenario at that time (although the father of my friend who was shot in the leg, did fly his flag at half staff). We did not speak for several months. Eventually our pride wore thin, our hearts grew heavy, and we moved on.

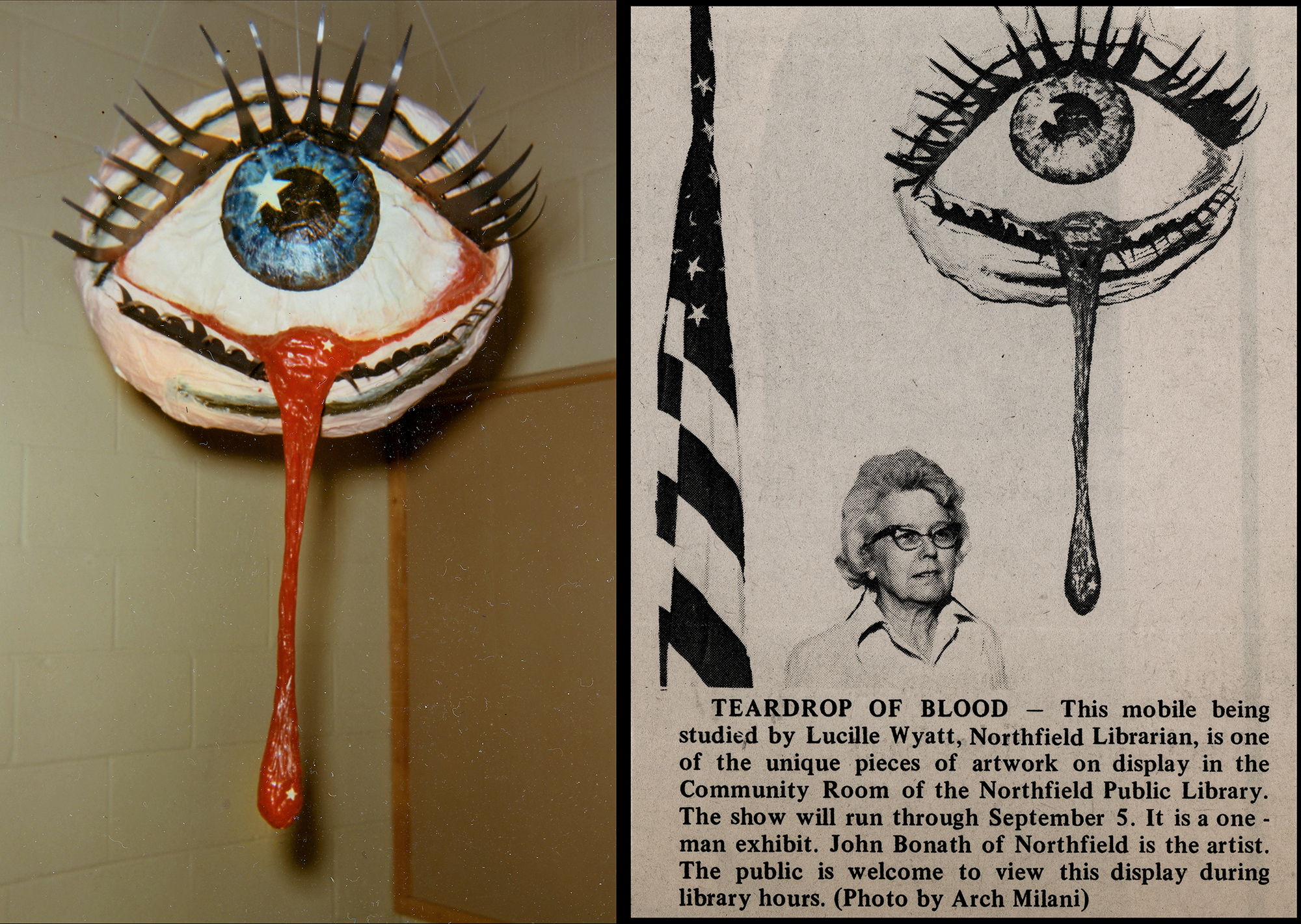

During that time, I produced my own version of an American flag through my art. As throughout my life, the “creative process” enabled me to heal, pull out of shock, express my grief and become whole again. Art has always been and continues to be an empowering vehicle which enables me to survive. This artwork was entitled “My Father’s Flag”. I was nineteen when I exhibited this piece in my first solo exhibition at the Northfield Public Library. My father was very proud.

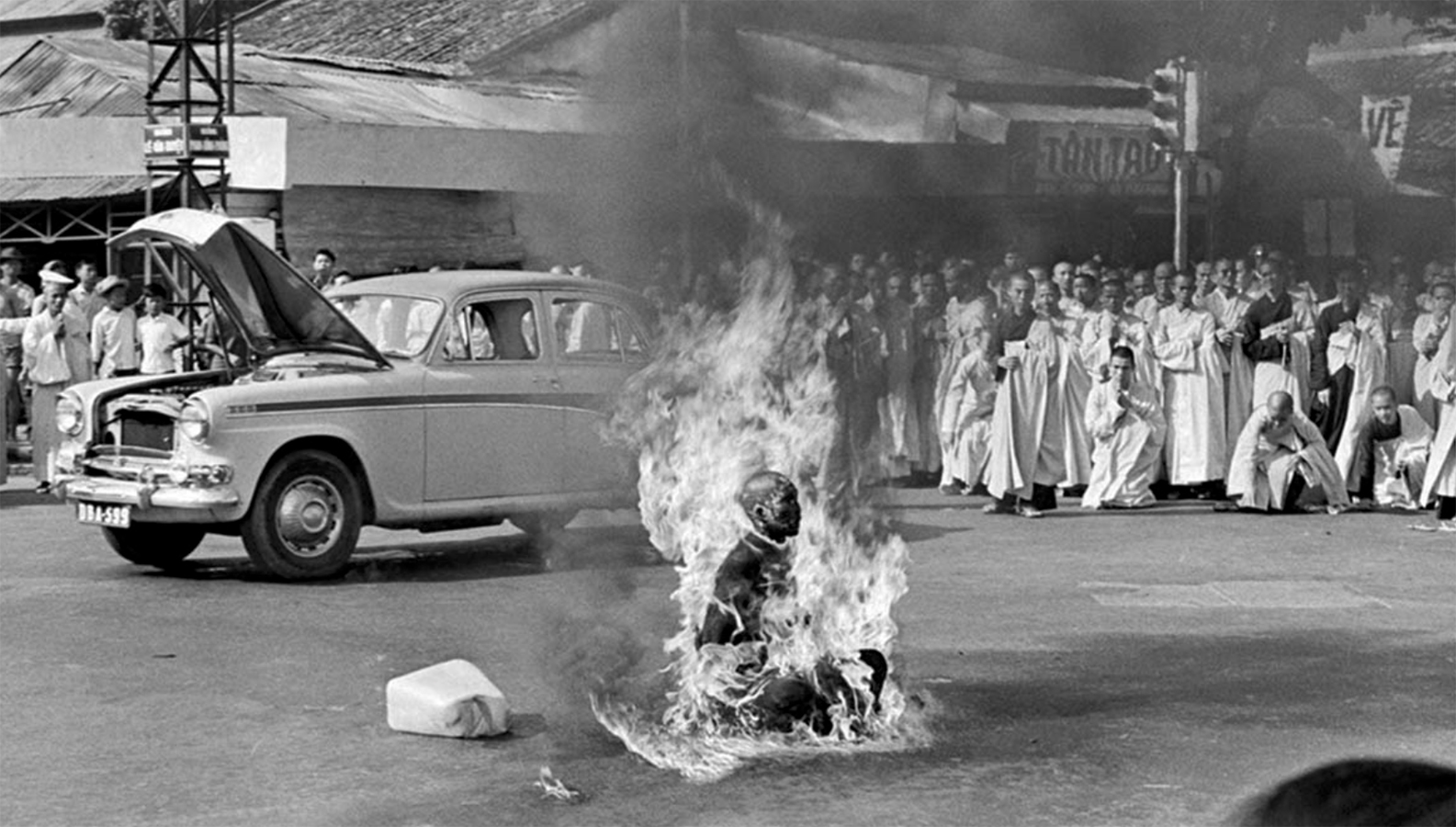

The awareness of a little-known country called Vietnam began during high school when the shocking front page sequence of photos of “the burning monk” was first published (a photo sequence of a Buddhist monk in meditation posture, with gasoline poured on himself, set himself on fire and calmly burned until his blackened corpse fell over). I was living in Cleveland when the end of the war was officially announced; people were cheering and whistling in the streets with elation while all the city’s church bells clamored in chaotic joy. “The Age of Aquarius” had come and was gone. More recently, Ken Burns produced an 18-hour documentary for PBS called, “The Vietnam War,” which is unsurpassed for its epic representation of this period in its full depth and complexity. To this day, Kent State has a memorial each year to honor the four students who lost their lives on that infamous day.

The famous sequence of a monk in Viet Nam burning himself alive without emotion (prior to the Viet Nam War) along with photos from Kent State on May 4th, 1970, including the Pulitzer Prize winning photo of the girl screaming over the body of someone just shot in the head.

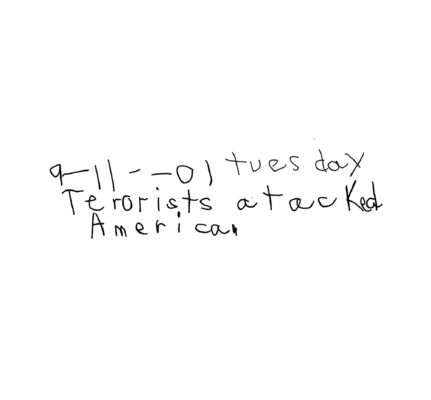

What I bore witness to when I was nineteen became a silent coal embedded in my psyche. Thirty-one years later, another event occured that resulted in the creation of yet another American flag. A moment where life as we knew it would never be the same. A moment no one escaped. What were you doing on the morning of September 11th, 2001?

The clear blue Colorado skies of that day started off normal enough for me. After dropping my son Casey off to first grade, I settled down to work. Turning on the radio, it was obvious that America was in crisis when the radio DJ suddenly broke down and cried on air. America was under attack. The reality-shattering images on TV were devastating and my immediate focus was to get Casey home to be with him. Most parents were doing the same. When we got back home, I held him in my lap and we watched the horror of the images on TV together, then the art supplies came out. Making art was already a part of our relationship and gave us a direction to focus, process and channel the emotional trauma. Two old thrift store sheets and the paints were spread out on the studio floor and gave us a large space to physically get lost in together. We were empowered with resilience as we put all our feelings and emotions into the creation of two American flags and some drawings. In the days that followed, I also responded with a still life of the two of us with Casey’s war toys, entitled “Warriors Enthroned.”

At such times of national identity, issues of diversity seem to dissolve into community. Individual identity becomes buffered with the national realization that we are part of a larger organism. The need for bonding is strong; unity is embraced. For us, this house became the vehicle for us to outwardly connect with others. We draped the two flags on the corner of the building as a rallying call that contributed to the energy in the air around us. The community response was great. The flags hung for a full year, flapping in the wind until they began to rot, tear, and disintegrate. Eventually one blew off the building and was completely destroyed. At that point, the remaining flag had become a permanent piece of the building and needed to be preserved.

The surviving flag was mounted on plywood with white glue and an iron; it was then coated with a heavy duty UV protectant (preserving the color from the harsh Colorado sun). The mounted flag was installed high on the southern wall of the house where it had good visibility and was safe from vandalism. It is now a familiar site to all who pass by. As my father had done before me, my house now flies the American flag daily as a public statement of who we are.

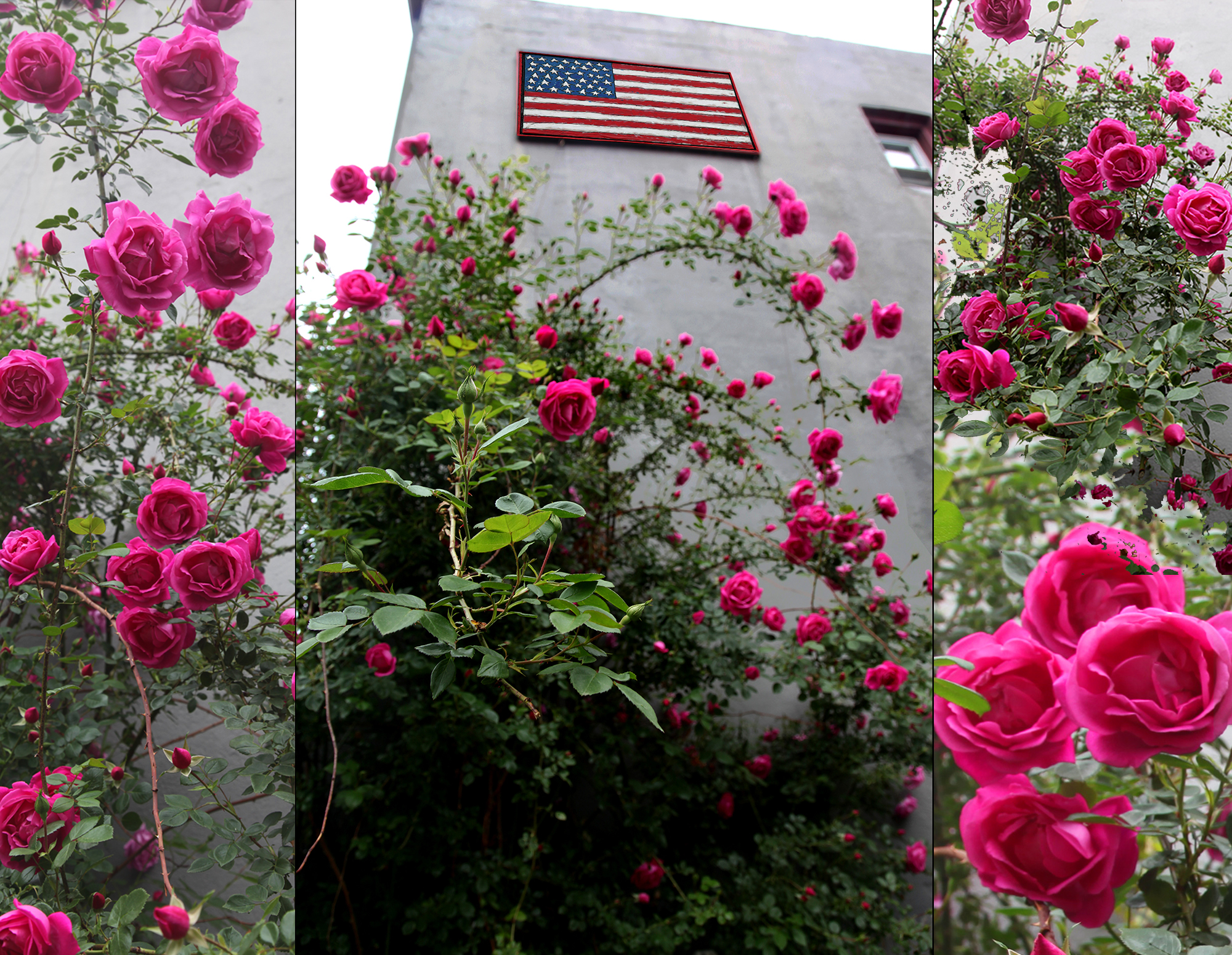

Every spring and summer, a brilliant pink rose bush explodes under the flag with an abundance of color; it grows from roots established far into the neighboring land for perhaps a full century. The vines grow upward on training wires attached to the flag. In the sense of a still life arrangement, the roses symbolize a positive life energy reaching upward to an American ideal. I don’t expect anyone to consciously think this, but everyone feels a Gestalt connection to the flag when the roses bloom.

Photos of the kinetic state of the roses relationship to the flag.

It is going on nineteen years since the flag went up. This last summer, the flag was restored. It will be around for many years to come. Perhaps some day in our lifetime, the roses will reach the flag.

If you liked this blog, please share and get others to subscribe to this website.

Pingback: Stories from the Hood, Part Three – The Gargoyle – John Bonath Fine Art Photography

Brian Scheuermann

I dont remember the family ever talk about the plane incident before, and never knew you were in Kent during that time. I love reading your blog cousin. I am gaining knowledge of your life experiences and I appreciate that very much. Thank you

Barbara

Wow! Heart wrenching, so much of it. Told so well. I especially liked seeing Casey on your shoulders, you know why?

Barbara

Wow! Heart wrenching, so much of it. Told so well. I especially liked seeing Casey on your shoulders, you know why?

Denver_Mike

This piece brought back memories for me. Yours is sharper than mine with more detail. A nice read. I would like the photos to scroll slower for us slow caption readers. I reflect on our times during the Vietnam War and how it’s divisiveness parallels what’s happening now. It gives me some comfort to know that we, as a country, were able to unite again – relatively – after that era ended. I’d like this or another blog to expand upon your relationship with Andy Warhol, and what he was like as a person.

Peter

John, blog is as intriguing as your photography. I am impressed with your writing skills. You are truly a renaissance man.

Deb

I love that the flag is an interpretation by Casey (and you) ad not an exact replica. The meaning doesn’t change but the expression is unique! Bravo!

Larry Martin

Love it, John!

Patty Martin

I love the variety of themes in this piece. There is so much here that I grapple with when dealing with my older relatives, as they are still dedicated to the ideals of conformity, consumerism, and violence. This is a fascinating piece and helps me to wrap my head around what my Boomer parents grew up with (the images of cigarettes, the Kent St students called “bums”, etc). I love this blog.