THE PHOTOGRAPHER: John Bonath, a CSU art professor, stands in front of his photographs in his exhibit ‘Burnt Cactus.’ His work on display through March 28.

‘Cactuses have a beautiful invulnerability. it’s very hard to destroy a cactus because you can’t get close to it. But here are these cactuses that were overcome. Their protective system was burned into black spots…’

John Bonath, Photographer

Read Full Coloradoan Article

“It is lovely indeed, it is lovely indeed. I am the spirit within the earth. The feet of the earth are my feet. The legs of the earth are my legs. …”

While John Paul Bonath perhaps hasn’t heard this chant from a Navajo song, his recent exhibit of platinum prints, “Burnt Cactus,” gives off the ember glow of that natural exchange the Navajos understand.

Bonath, a photographer and associate professor of art at Colorado State University, has a way with subjects – even the lowly prickly pear cactus, that plant many curse for its sharp exchange of needles into bare feet or legs.

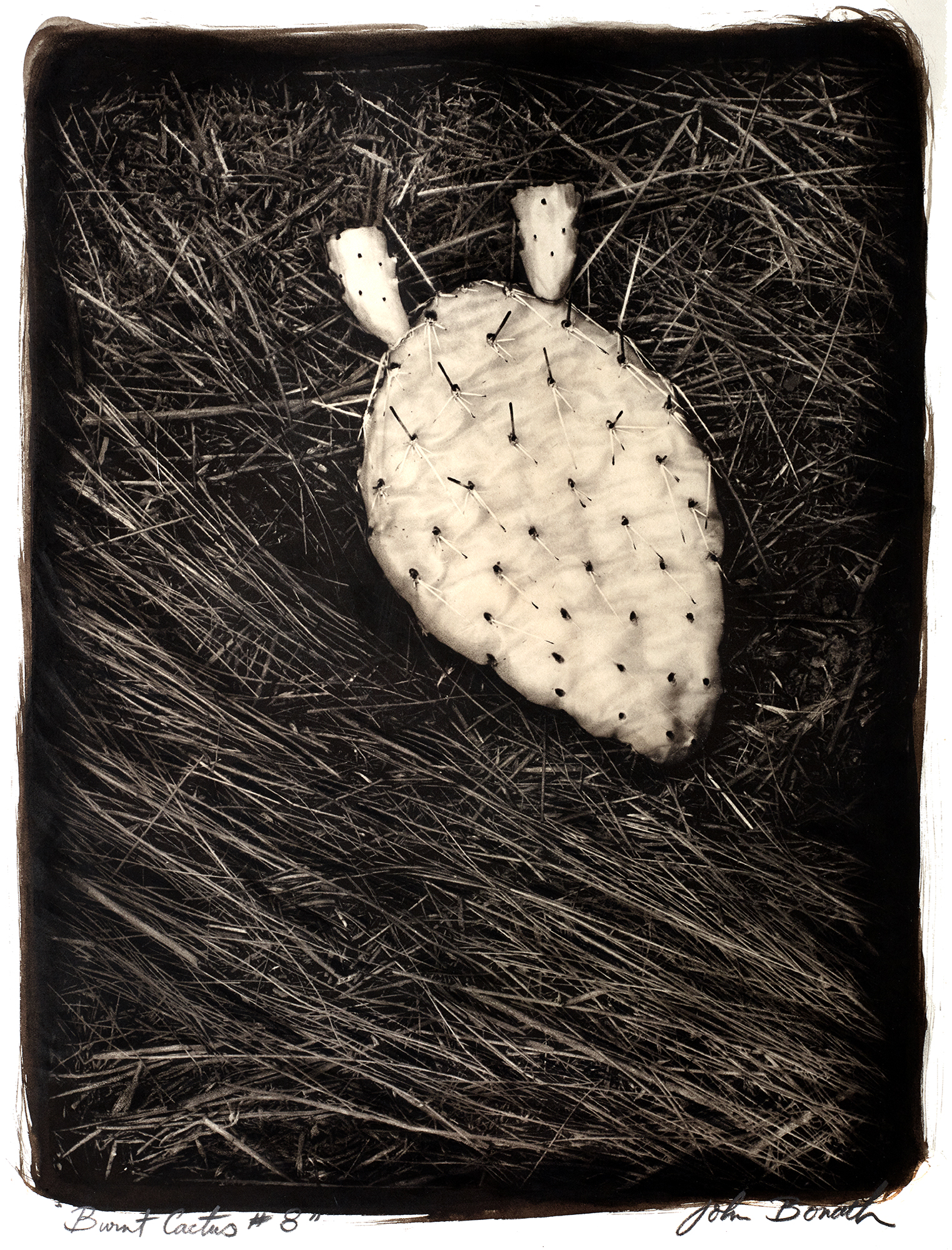

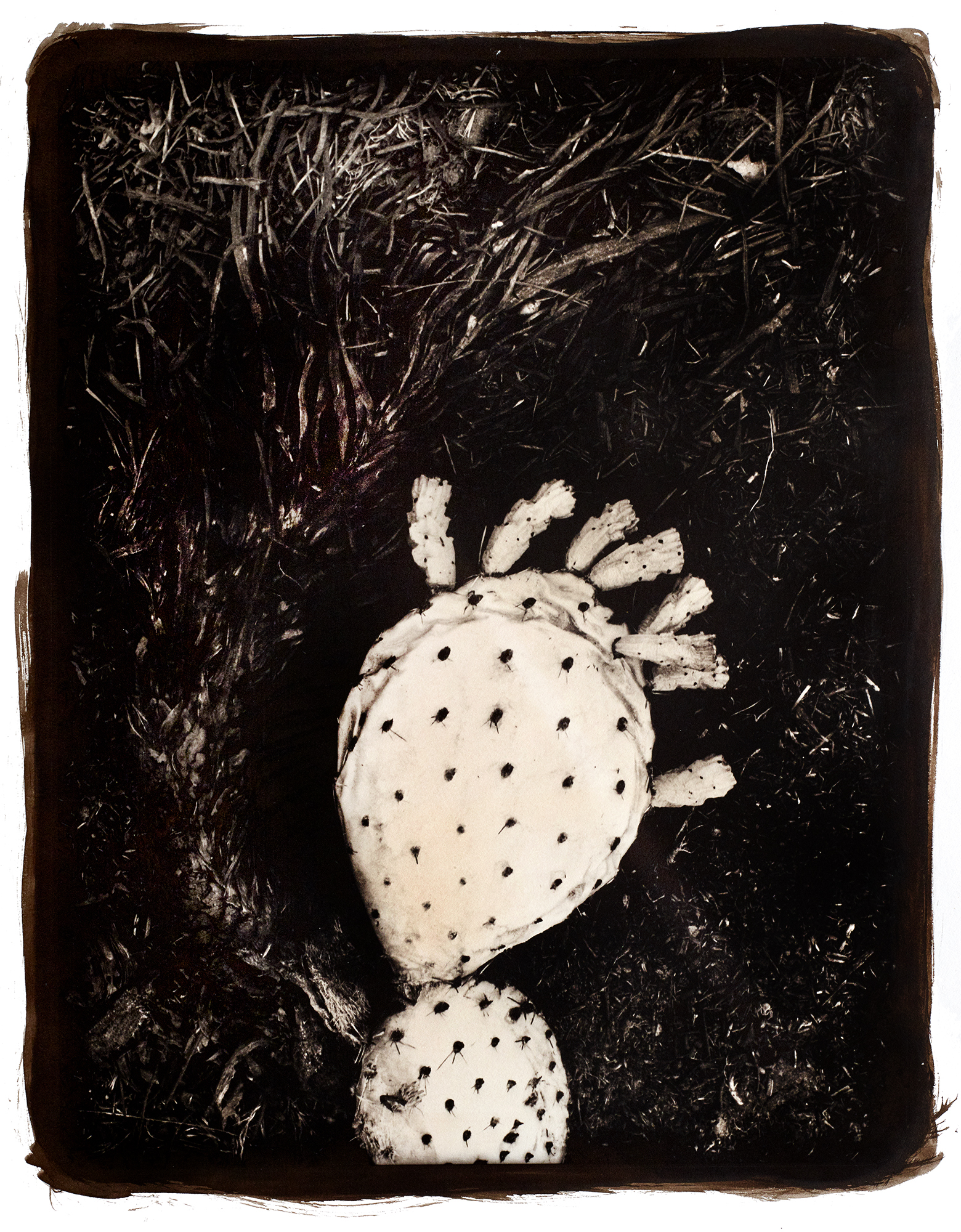

Bonath’s cacti, the main subject of his show of 17 photographs in the Directions Gallery of Colorado State’s Visual Arts building, grow into themselves and out again into all manner of beasts. The transformation is due as much to the photographer’s eye as to the printing technique he uses to render what he sees as “the dual reality of these peculiar cacti.”

Burned in an out-of-control brush fire, the combative cacti which would make their way into Bonath’s photographs, lost their needles, withered and turned white.

“When I came across them, I was startled by the contrast of the white cactus against black grass,” recalls Bonath. “They aren’t like this in full growth, with the figure/ground so pronounced. Design-wise they had incredible impact.”

On another level they had an even more profound effect on Bonath. “Their skin had become very human like, waxy, soft, folded. Like skin I remembered on my great grandmother.”

Made into photographic subjects, the burned cacti’s fleshy, wrinkled, pock-marked remains eerily extend into lyrical shapes that for an instant echo a bird, or a fish, an ant, a primordial foot or perhaps two turtles mating. But the instant passes, and the cacti change again into themselves – or into the antithesis of themselves.

“Cactuses have a beautiful invulnerability. It’s very hard to destroy a cactus because you can’t get close to it. But here are these castuses that were overcome. Their protective system was burned into black spots. What’s behind them can now be destroyed.

“For me the burned cactuses took on human attributes. I think of them as portraits that represent certain emotional states.”

In “Burnt Cactus 12,” for example, the cactus assumes the simple, sure shape of a child’s drawing of a fish and seems to swim gleefully in front of the netted, grassy background.

In Burnt Cactus 2,” the evocative three-padded cactus seems to stoop precariously forward like an ant with an over-sized head trying to balance itself on painfully spindly legs.

Typical of all good portraitists who bring out the lyrical as well as the pathos of a subject, Bonath has come to know his subjects well. Having previsualized, that is, seen their potential to trigger a certain feeling, Bonath had the more difficult, technical task of bringing that feeling into focus.

For this he chose platinum, for his printing emulsion, spending about eight to 10 hours on each print.

‘Platinum offers a quality you’ll never see in silver-gelatin prints, which is what most black and white photographs are. Platinum gives a rich black, deep in value, one that is softer in feeling but produces a clear image. It makes the image feel dreamlike.”

Bonath explains that platinum which is brushed onto 100-percent rag paper, produces an image that has a richness not unlike a printmaker’s etching.

The transformative nature of Bonath’s 20 inch by 24 inch prints comes from the quality of platinum’s “blackness” and the required brushwork.

Brushing on the emulsion allowed Bonath to soften the edges of the prints so that they became less like “little pieces of reality mechanically chopped out by a camera.”

“Like a poem or haiku, I wanted the ‘Burnt Catus’ prints to be lyrically evocative in feeling, triggering something rather dreamlike without losing their literal identity.”

Another series of photographs in the show is called “Pancake Rocks, New Zealand.” The size of these photographs, 32 inch by 32 inch, ad their sharp focus remind Bonath of television screens, he says. “it’s photographic reality, the world in a box,” he says of the lusciously textured and layered close-ups of rock formations.

Bonath, an equally accomplished draftsman, ceramist and painter who draws freely on techniques from those mediums when producing his work, settled on photography as an art form because “the psychology of photography is what appeals to me.” he explains.

“I like the idea of viewing reality through another reality. Just like with the cactus. Their forms alone have the ability to channel feeling and emotion into a new reality of expression.

“I like the idea of not being able to grab on to the edges. Outer reality is someplace and we’re viewing through into another.” – by Melissa Katsimpalis

The exhibit, which runs through March 28, is open to the public without charge. Gallery hours are Monday-Friday from 8 a.m to 4 p.m.

‘Cactuses have a beautiful invulnerability. it’s very hard to destroy a cactus because you can’t get close to it. But here are these cactuses that were overcome. Their protective system was burned into black spots…’

John Bonath

Photographer

Landscapes

Read about how a platinum print is made

Black and white photographs that are traditionally printed in a darkroom are printed on a factory-made photographic paper. This photographic paper uses actual silver to make the image. In the platinum process, the blacks in the images are made using real platinum.

All these images are shot using traditional black and white film. From these original negatives, a special large film negative is made in the darkroom, at the size of the final print.

The platinum chemistry is measured and mixed under dim light. This liquid “emulsion” is then brushed onto an art paper that is capable of being put in water without falling apart. The “sensitized” paper is dried in a dark room and is then sensitive to light. The large film negative is then placed in tight contact with the paper.

A strong ultraviolet light source is used to expose through the film onto the paper. The sun can be used, but I built a special “light box” using strong ultra-violet light bulbs as the light source for my printing.

The light goes through the film negative and onto the paper. The light will harden the platinum where it is strongest and will harden it less where it is blocked by the dark areas on the film negative. After exposing the paper like this for about 30 minutes, the paper is developed. Where the light has hardened the platinum emulsion, it is dark; where the light was blocked by the film, it rinses off the paper. The paper is then put through hours of special hand rinsing.

The finished print is then taped on a board, like an etching. In this manner, the paper will shrink and be stretched perfectly flat when it is dry. After a print is completed, I add more platinum to special areas of the print by hand.

The entire process takes about a week to make a single print.