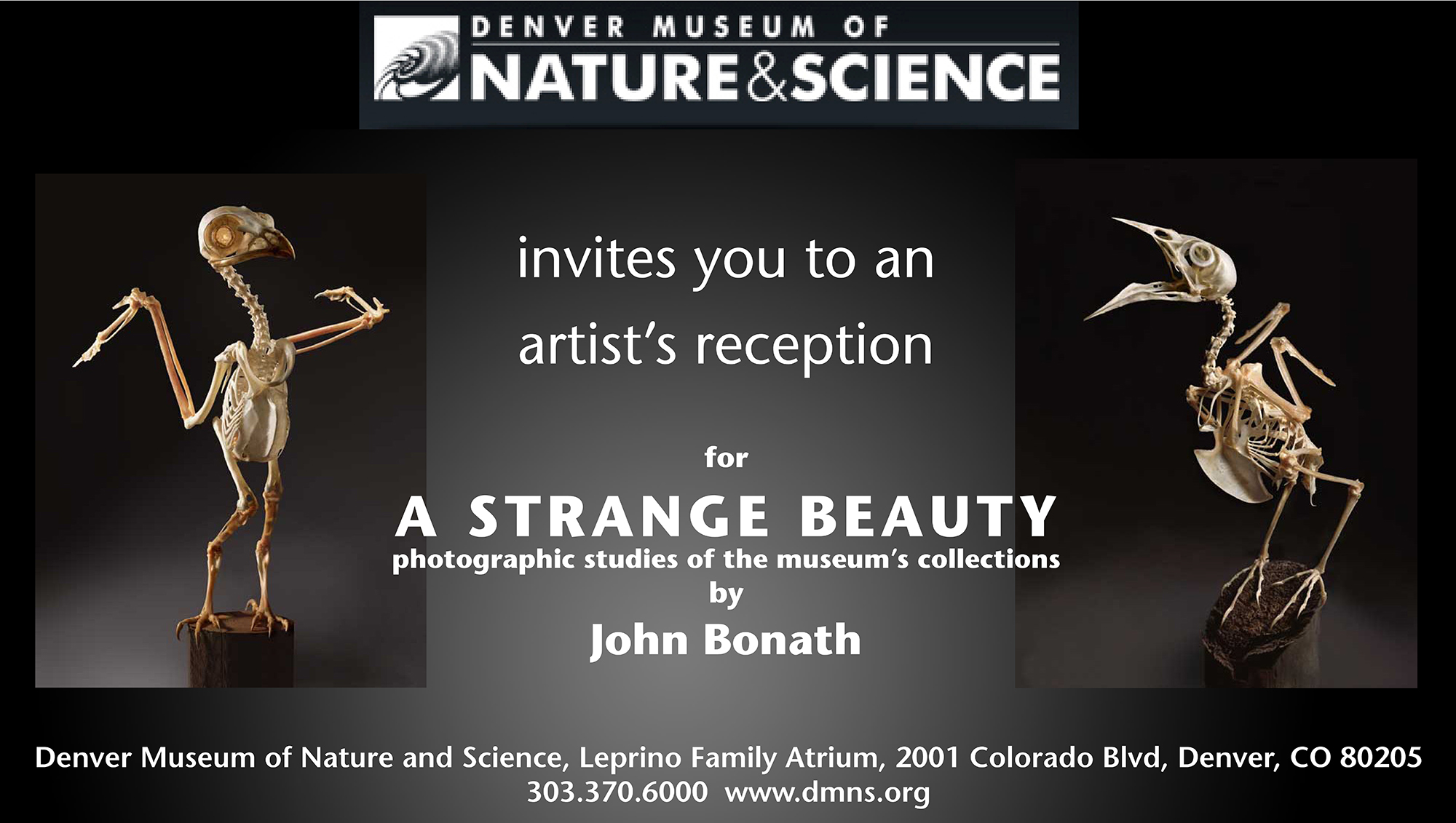

A STRANGE BEAUTY

photographic studies by John Bonath

from the collections of THE DENVER MUSEUM OF NATURE & SCIENCE

READ WESTWORD REVIEW OF SHOW BY SUSAN FROYD

John Bonath on A Strange Beauty at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science

SUSAN FROYD | October 25, 2011

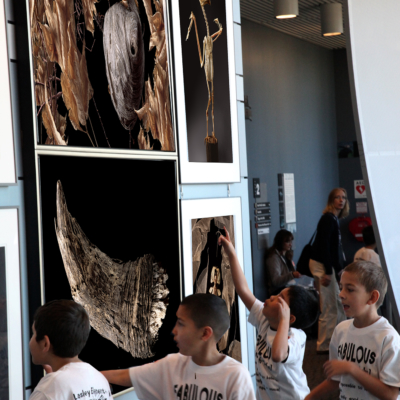

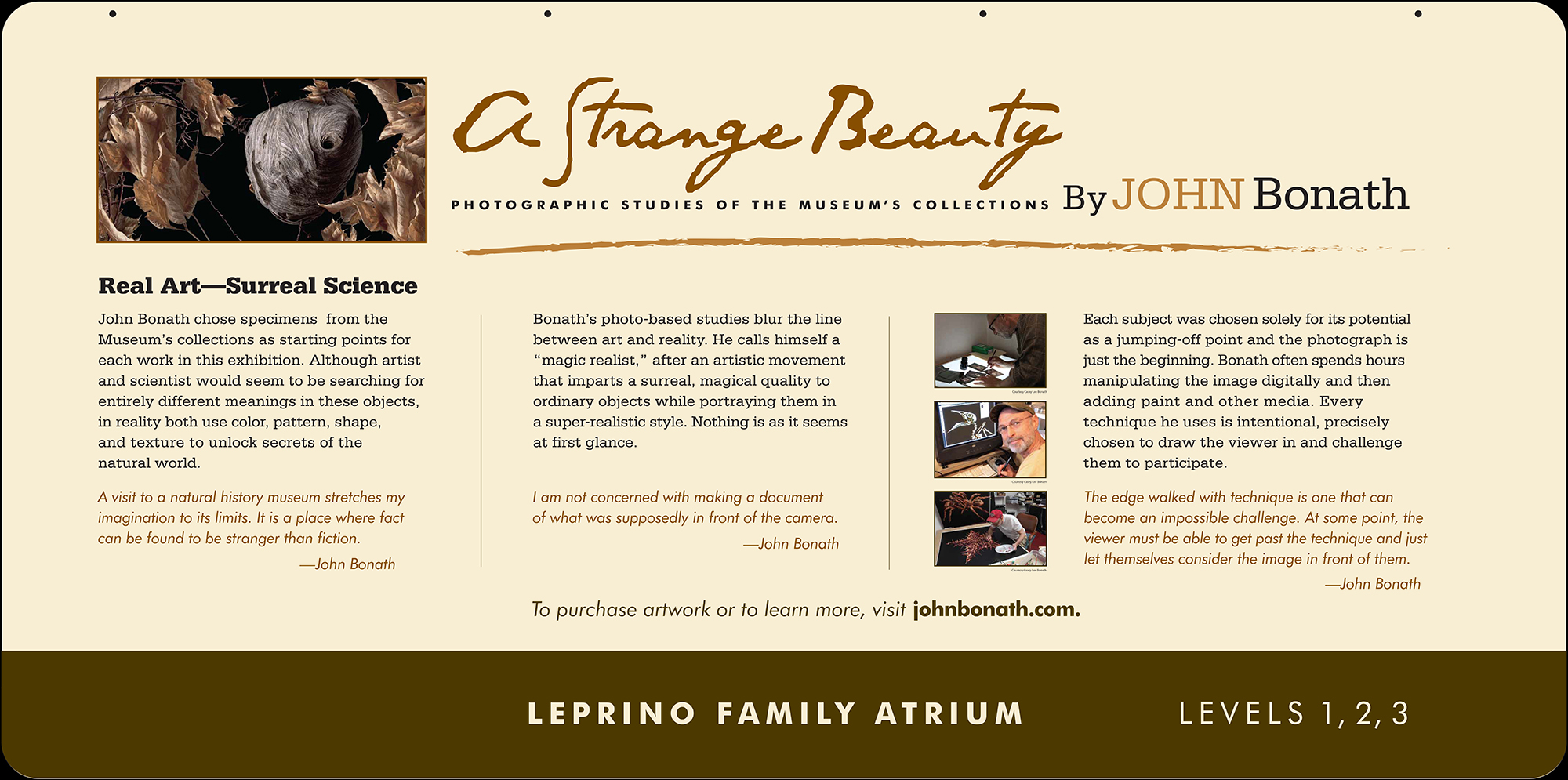

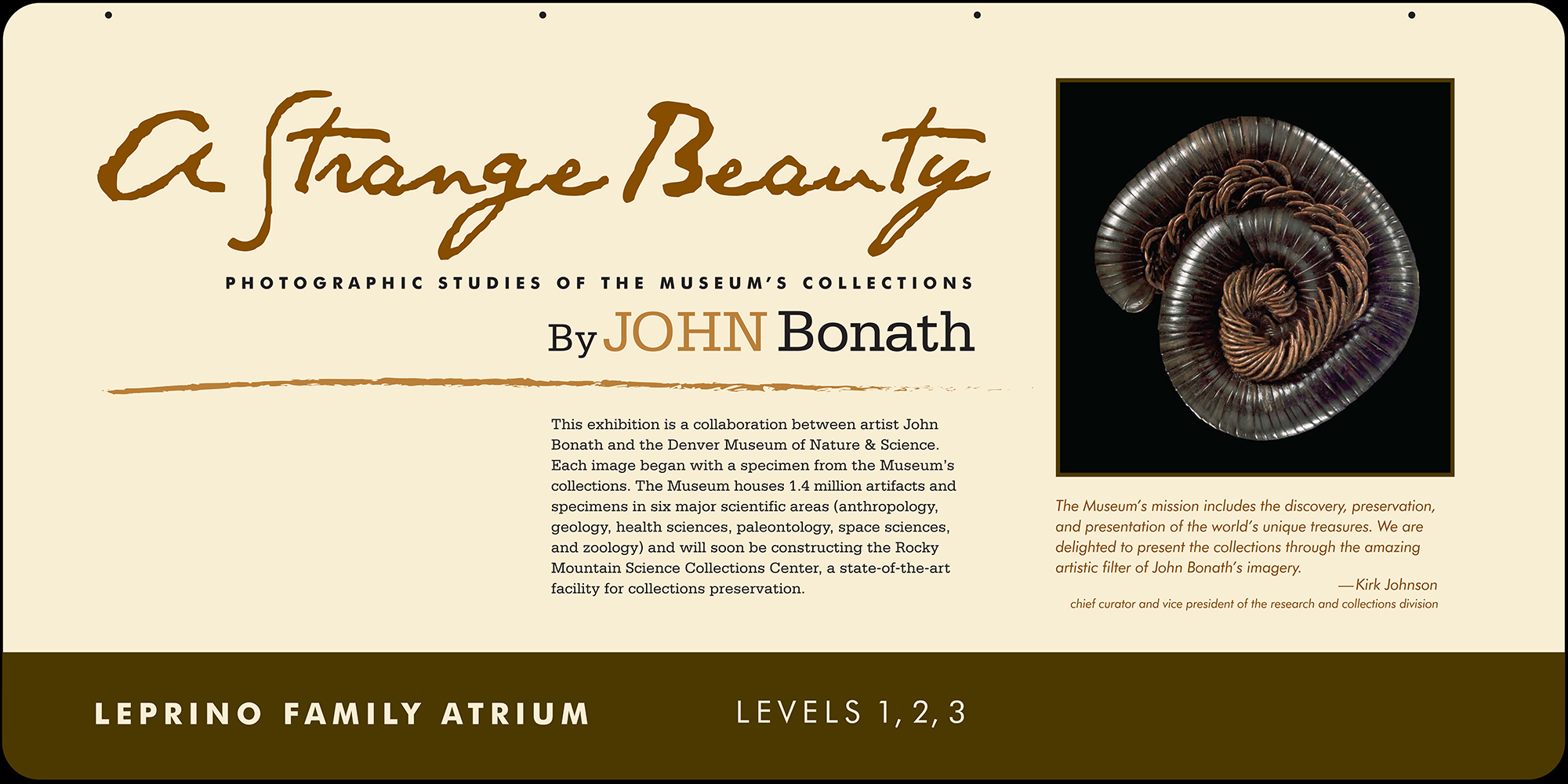

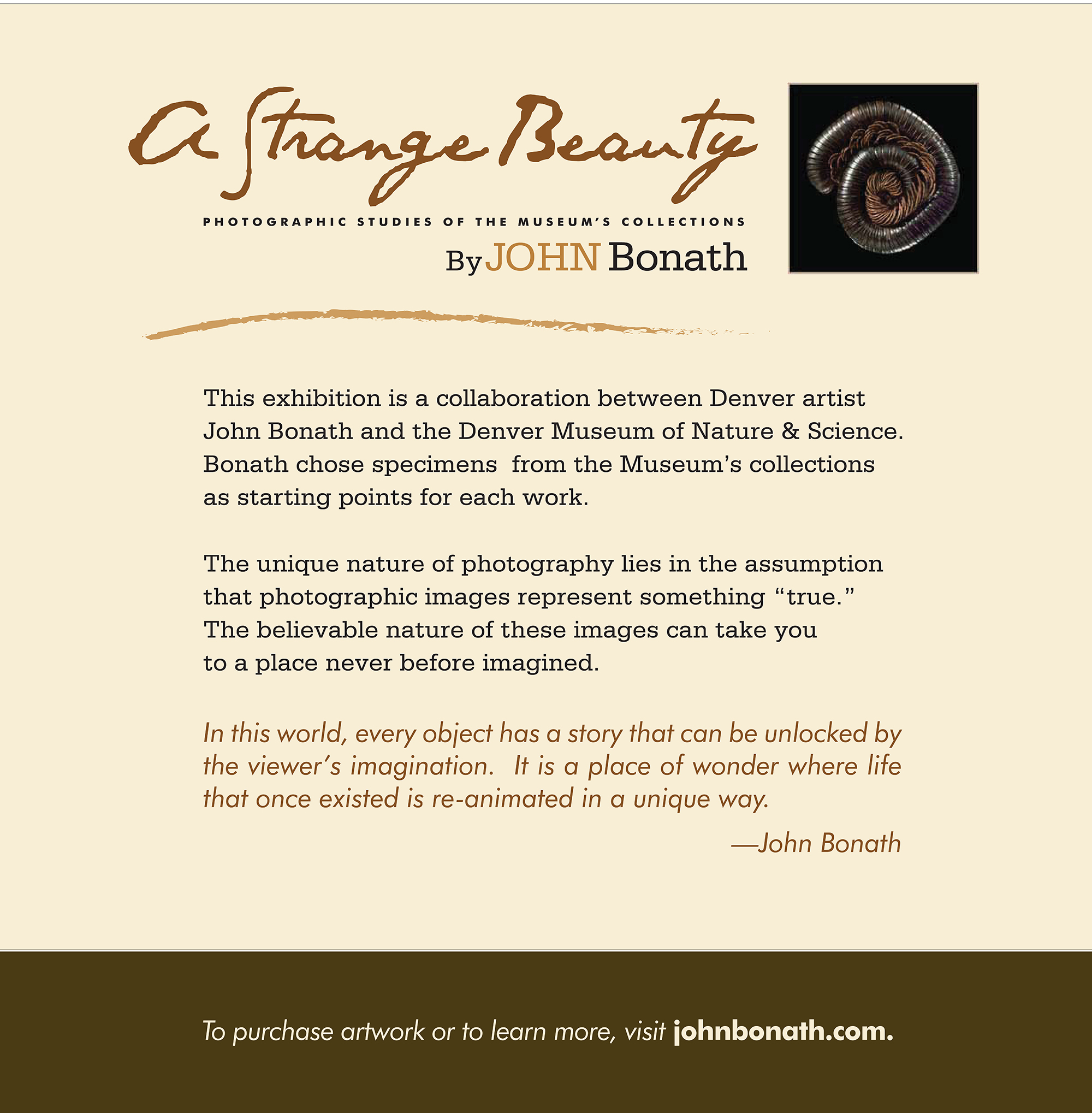

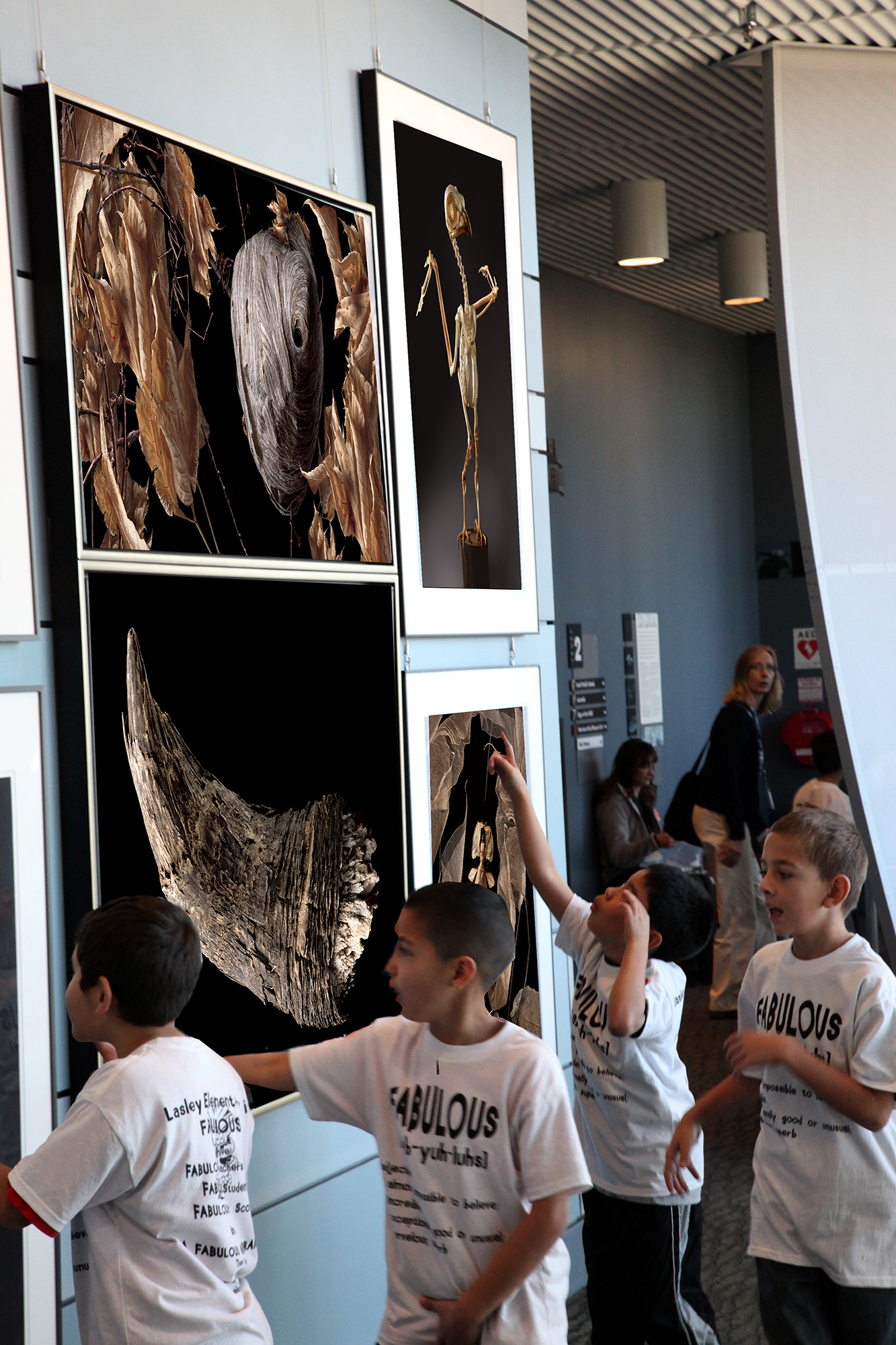

Photographer John Bonath’s spectacular three-level show, A Strange Beauty, which opened at the end of September at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, encourages visitors to explore a massive, hidden-away portion of the museum collection in an unusual and contemporary way. The hand-chosen objects that Bonath re-examined through an imaginative lens for the exhibition not only take on a new life, but encourage an entirely new audience to step over into the realm of art appreciation. And for Bonath, this is a welcome step outside of the usual gallery experience, where people of all ages are invited to participate in the creative process.

Bonath and DMNS zoology collections manager Jeff Stephenson will offer some insight into the show’s art/science crossover during a lecture tonight at 7 p.m. at the museum.

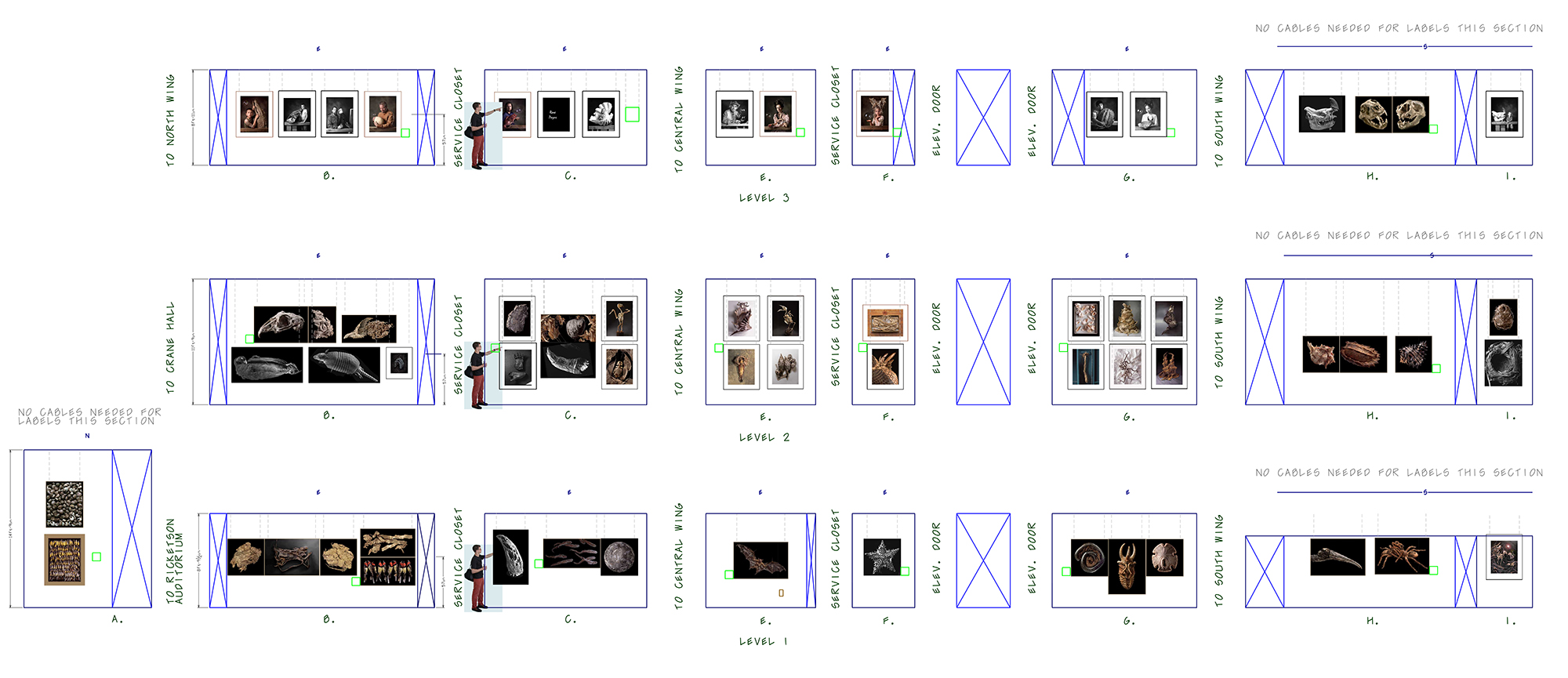

“It’s more than a show,” Bonath says of the mammoth exhibit, which encompasses 62 large-scale works. “It’s more like three huge solo shows on three floors. There’s been nothing like that ever before there. They’ve never, ever used the third floor of that space for anything, but it’s such a great space.” And just as the show brings the archive out in the open, it also represents a rare collaboration between museum scientists and the artist.

“They’ve been so supportive,” Bonath explains. “I’ve worked with so many people in different departments and programs — all these managers and curators in the collections, the productions team — that I felt like I needed to clone myself just to try and keep up with them.”

It also helps that Bonath had nearly complete freedom in his use of the vast collection. “I could look through 1,500 things, going through drawer after drawer,” he remembers. “It was such an adrenaline rush. I would take little snapshots to remember what I think I might want to review, maybe 150 of them, and then I’d spend hours going over them to edit them down and come up with ideas. So I would eventually edit my list down to ten, and then I’d e-mail the manager and say, ‘I would like to work with these things. What is their status?’ The collections are open to the public, but nobody knows they exist, and getting access to them is not so easy. I come in and start showing people this whole world behind the scenes, and it’s win-win for everybody. I can bring the collection to the people, who will see it in a different way.”

Though he doesn’t admit it, in conversation Bonath reveals himself to be something of a scientist, too, ever concerned with things that most of us don’t think about, like the way light can affect how we see a work of art.

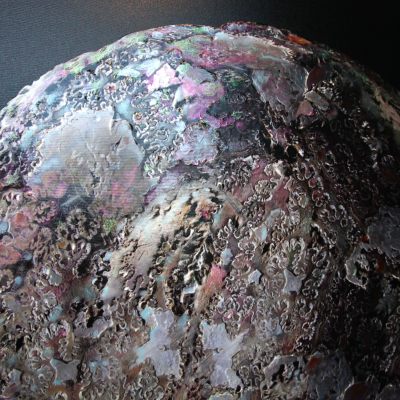

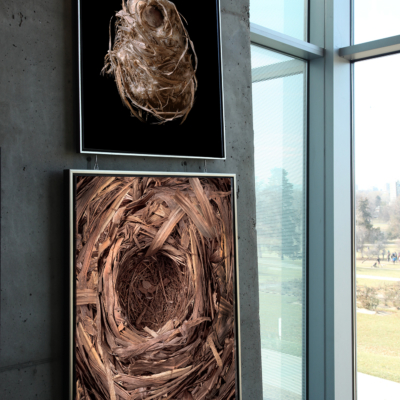

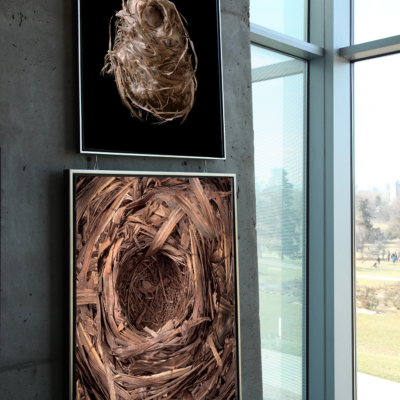

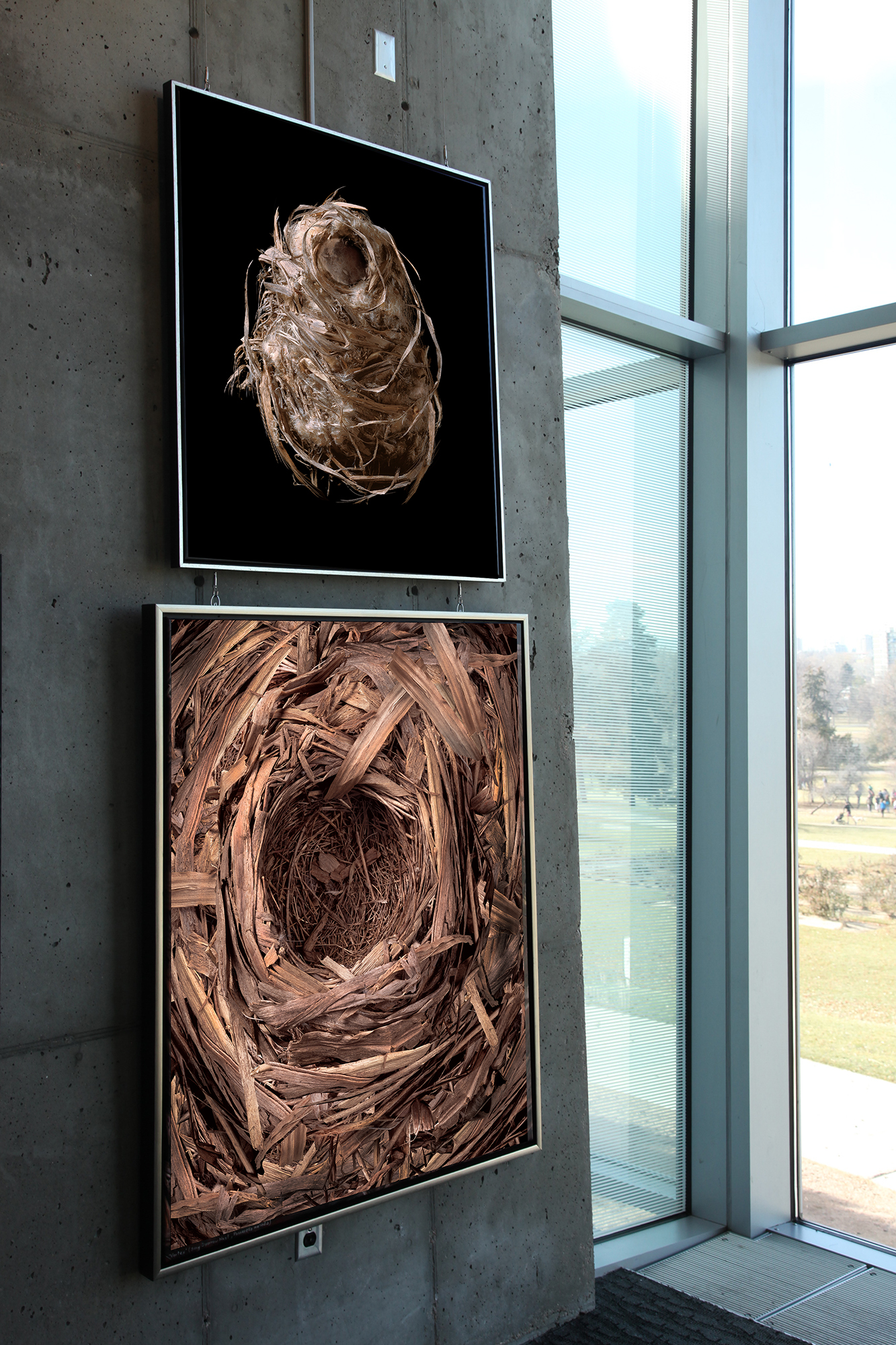

Some of the pieces in the show, which are built up with pigments, have a dimensional quality and an iridescence that are enhanced by the glare from the museum atrium’s three-story wall of windows. “It brings out little things you might see only in certain instances,” Bonath notes. “That glare adds a thing that no one’s ever seen in them before, and it changes at different times of day.”

Now that the exhibit is up, Bonath is also finding that a show at an institution like the DMNS offers a better way to connect people to the art experience. “The more I work in art, the more I get tired of things being so inaccessible to people,” he says. “At some galleries, there’s somebody in every corner of every nook standing there to make sure I don’t touch the art. At the Nature & Science museum, there are kids bouncing around, people talking. People are excited, and the air feels alive. It’s real. I love going there for so many reasons.

“After the public wandered in and saw it, a seventy-year-old lady called the museum,” he adds. “At length, she went on, reprimanding then for not promoting the show better. She said, ‘I’m seventy years old, and I don’t know much about art, but this kid is a genius. Seeing this show is like hearing a Mozart sonata for first time.’ I get choked up thinking about that.”

A Strange Beauty remains on view at the DMNS, 2001 Colorado Boulevard, through next February.

READ COMMENTARY

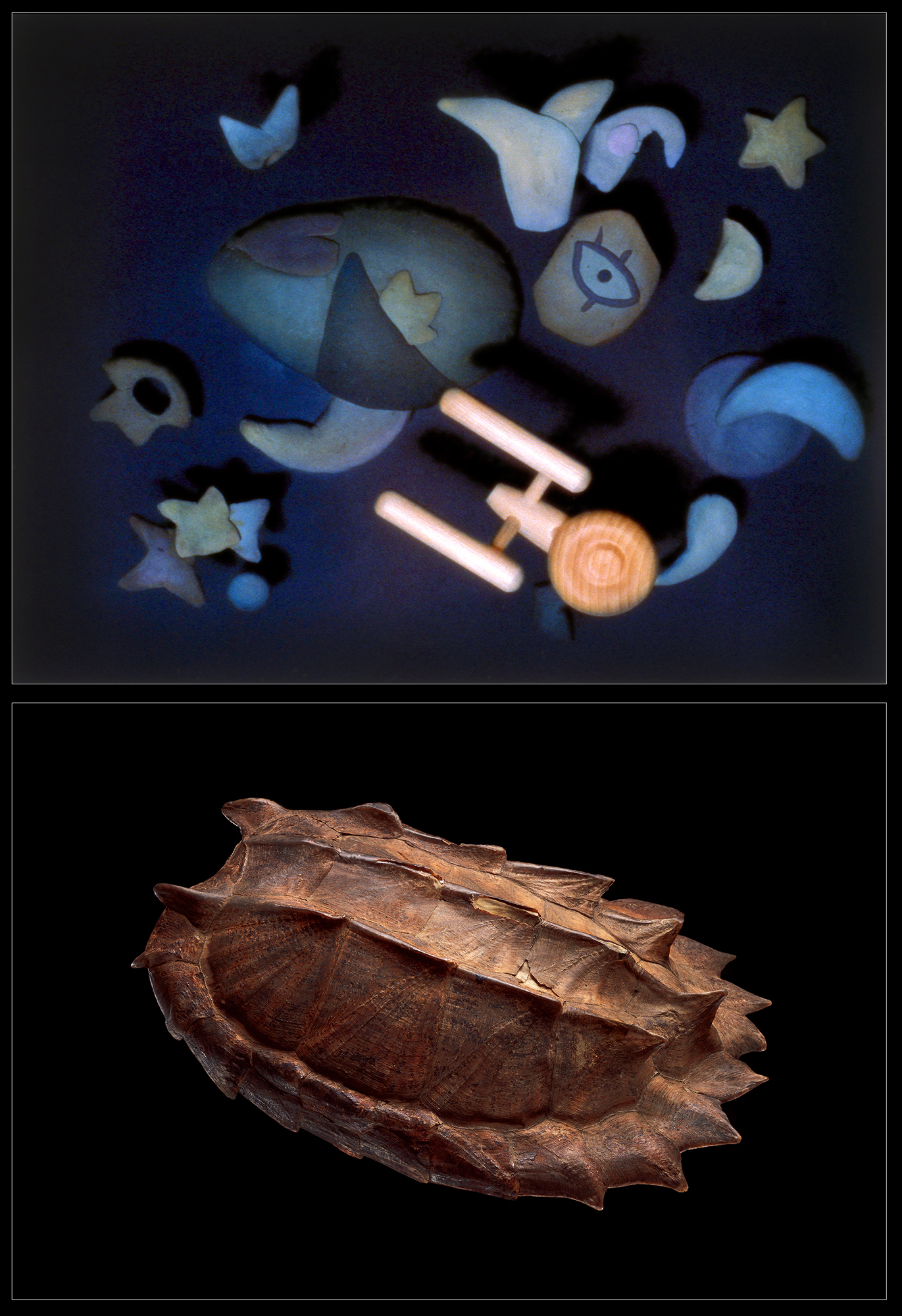

The still life fabrication from 1979, is from a series where the little wooden spaceship was used as a metaphor for exploration into our sub-conscious psyche. In ancient Egyptian religion, the turtle represents a time in the history of the universe referred to as the primordial waters – a time before light and a time before the big bang. Although this reference is extremely obscure, the turtle existing in the pre-conscious, dark waters of the universe is a beautiful metaphor for our conscious attempts at understanding the sub-conscious.

The idea comes from the basic principle of ancient Egyptian cosmology and the Primeval Waters. Although the details vary, every ancient Egyptian creation myth assumes that before the beginning of things, the Primordial abyss of Waters was everywhere, stretching endlessly in all directions for infinity. It was not like a sea for it had no surface or bottom and was not contained. There was no region of air or visibility. All was dark and formless. In one popular version of the creation myth, there was an invisible egg, which took shape before the appearance of light. In fact, the Bird of Light burst forth from the egg. This egg not only contained the Bird of Light but also air and the breath of life. This egg was laid by a goose known as the Great Primeval Spirit. This bird was the Great Cackler whose voice broke the great silence. The hatching of the egg with the Great Cackle, is similar in essence to the contemporary Big Bang Theory of creation.

In one of the Book of the Dead spells, the Primeval God assumed several forms as its seed grew to disguise itself. One of these forms was the tortoise, which I refer to in this image as a form slowly moving in the dark, watery abyss – much like a space station as it eloquently glides in a gravity-less space. The explosive tortoise shell contained the light of the first morning, the beginning of life and existed in a black infinite abyss prior to any state of consciousness. The turtle shell was a vessel which contained the seed of consciousness in the primeval abyss of darkness.

In 2011, this same turtle metaphor reoccurred in The Strange Beauty series, titled “Ancient Voyager”. The turtle is one of the most unique, pre-historic life forms on earth. In this image of a giant alligator-snapping-turtle shell, the ancient form was placed in a dark space to give a feeling of an infinite void. The simplicity of the composition emphasizes the perfect, natural aerodynamics of the form as it silently moves through black, cosmic space. It is much like a spaceship, smoothly moving through the infinite space of the universe.

Related Work

SIGN UP FOR JOHN’S BLOG

Copyright John Bonath 2019

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Pingback: A STRANGE BEAUTY, Westward Review – John Bonath Fine Art Photography

Pingback: CPR Interview with John Bonath – John Bonath Fine Art Photography